Behind the Lens

Revealing the World: Steve McCurry

Published

2 years agoon

By

Jain Kelly

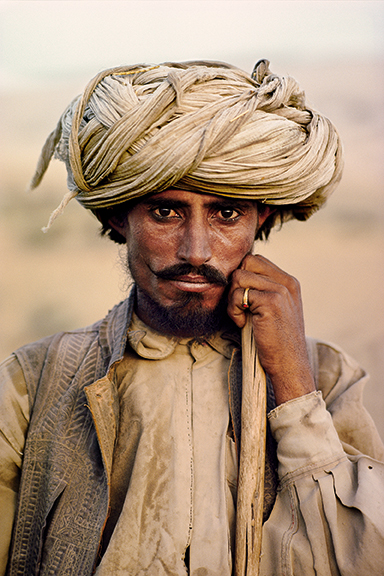

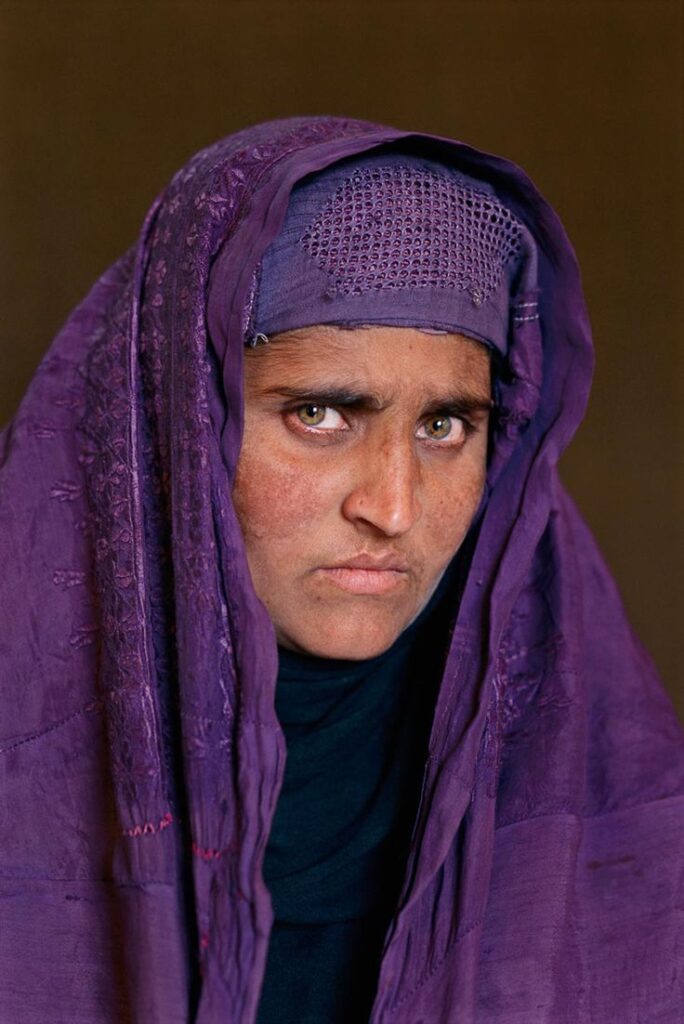

Of the many well-known documentary photographers, Steve McCurry is regarded as one of the most respected by his peers and one of the most recognized by the general public. His stories have ranged from the life-giving cycle of the monsoon to the disastrous effects on the environment by Saddam Hussein’s burning of the oil wells in Kuwait. A high point in his career came in 1984 with his portrait of a 12-year-old Afghan refugee girl with penetrating green eyes, a portrait that has become world famous. His search for the girl 17 years later and his rediscovery of her resulted in headlines: “Afghan Girl Found.” An indefatigable traveler, McCurry spends months of each year photographing in Asia, often in dangerous circumstances, adding to the ample archive of images upon which to draw for his numerous books. These books include The Imperial Way by Rail from Peshawar to Chittagong, with Paul Theroux (Houghton Mifflin, 1985); Monsoon (Thames & Hudson, 1995); Portraits (Phaidon, 1999); South Southeast (Phaidon, 2000); Sanctuary: The Temples of Angkor (Phaidon, 2002); A Path to Buddha: A Tibetan Pilgrimage (Phaidon, 2003); Steve McCurry (55 Series), by Anthony Bannon (Phaidon, 2005); Looking East: Portraits by Steve McCurry (Phaidon, 2006); and, most recently, In the Shadow of Mountains (Phaidon, 2007).

Steve McCurry’s career was launched in 1979 when he crossed the Pakistan border into Afghanistan shortly before the Russian invasion. One of only a handful of photographers who had entered the country to document the countrywide insurgency against the Afghan government, he returned with rolls of film hidden in his clothing. As the world began to understand the importance of the emerging conflict in the region, his photographs were in demand and he received offers of assignments from Time Magazine and National Geographic. His coverage of the events in Afghanistanwon the Robert Capa Gold Medal for Best Photographic Reporting from Abroad in 1980.

Although McCurry is best known for his stories for National Geographic, he has published in many other major magazines and newspapers, including LIFE, Newsweek, Paris MATCH, Der Spiegel,and The New York Times. The National Press Photographers Association named him Magazine Photographer of the Year in 1984. He received four first prizes in the World Press Photo Contest in 1985 and became a member of Magnum Photos in 1986. McCurry is a two-time recipient of the Overseas Press Club’s Oliver Rebbot Memorial Award. In 2002, he was given a Special Recognition Award by the United Nations International Photographic Council in acknowledgement of ceaseless devotion and outstanding achievement in photography.

What was your childhood and youth like?

I was born in 1950 and grew up in a suburb of Philadelphia. As a kid, I loved sports and played in the woods near our house. I had two older sisters, Jean and Bonnie. My father was an electrical engineer. My mother died when I was eight years old. After her death, my father was overwhelmed by taking care of three active children. I had a lot of energy and was always a bit of a wild child. He thought that the regimen of boarding school would be helpful in terms of discipline and character building. So he sent me to boarding school when I was twelve, which was one of the dark periods in my life. Boarding school was tedious and stifling and just not a lot of fun; I tried to escape from that at the first possible chance and was able to return home after a year. After high school I went to live and travel in Europe and the Middle East for a year. That was important because it really got me interested in exploring the rest of the world. I decided that whatever I did in the future, traveling the world would be part of my life.

I worked odd jobs in Stockholm and in Amsterdam. I worked on a kibbutz in Israel. Life on the kibbutz was fascinating. We worked for two hours before breakfast and then late into the day, but I was learning about the value of community, hard work, and cooperation. I also went through Turkey, Bulgaria, and Yugoslavia.

At what point did you start college and where did you go?

After traveling in Europe for more than a year I went to college when I was twenty. I went to Penn State University.

Is that where you got interested in photography?

While I was in college, I traveled during my summer vacations, going to Central America and to Africa. I financed these travels by working. I hitchhiked through Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Panama. I was photographing along the way and then came back to Pennsylvania.

My father had always been interested in photography. He had an old Argus C-3 35-mm camera and a box of slides he had taken when he was a young man.

In my second year of college I took a cinematography course, and in my third year I took a fine-art photography course. I didn’t even own a camera, but the department had cameras we could borrow. We had a couple self-assigned projects: portraits and our own independent study. I came up with an idea of shooting windows and doors. During that time, I started doing assignments for the college newspaper. I was also studying photographers like Diane Arbus, Dorothea Lange, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and André Kertész. Probably my first approach to photography was influenced by these photographers. I was always drawn to street photography.

How did you make the leap into professional photography?

When I graduated I started making pictures for a newspaper outside of Philadelphia and selling them for $5 a picture. Eventually I got a staff job on this newspaper and I did that for about two-and-a-half years. I started looking for other challenges. I also wanted to travel. I started investigating my options. I took a few workshops — one with photographer Elliott Erwitt, one with Ernst Haas, and one with picture editor, John Morris — and decided I wanted to freelance. I saved my money and started looking around for small magazines that couldn’t afford to send me to a place but that would buy a story for a few hundred dollars. That would be enough to keep me going. India seemed like a good choice because so many great photographers had worked there. I’d already been to Africa and Latin America, so I thought, OK, let me go to India for six or seven weeks. I went with a friend who is a photographer and writer. We knew we could live on a few dollars a day and have some great experiences.

I’d been in India for two weeks when I got amoebic dysentery. Within the same couple of days I came across a rabid dog and had to get rabies shots. That was back when you had to get a series of shots in the stomach. It was really painful and I was delirious. What had originally been a six-week trip to India turned into two years. During those two years I bounced around India, Nepal, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Thailand, getting to know the region.

Up until then I had been shooting in black-and-white but switched to Kodachrome overnight. It was back in the days when it was difficult getting Kodachrome processed in India, so I had to send it back to the States. I had someone look at it to make sure the camera was working and all that, but I was never actually able to see my own pictures for about a year and three months.

Most people in the West weren’t paying much attention to the region then. But wasn’t it just becoming a political hot spot?

There was a civil war just beginning in Afghanistan. In June of 1979, I met some refugees in a cheap hotel in Chitral, Pakistan, who invited me to go into Afghanistan to photograph and see the situation. When they came for me the next morning, I was having second thoughts, but I wanted to honor my commitment so I went ahead. They referred to themselves as Mujahideen. They were part of the uprising that was turning into a civil war. They were fighting against the newly installed communist government. The Afghan army was punishing them in turn by bombing and actually decimating whole villages. At this point, there wasn’t much information or interest about the situation in Afghanistan. But when the Soviets invaded later that year, it became a huge, international story.

Why were the Soviets so concerned about Afghanistan?

The Afghans’ resistance to the Afghan government was becoming strong and building day by day. The Soviets became nervous that unless they propped up the fledgling Communist government they would lose a client state.

The Soviets decided to go in and give the government help in putting down the insurrection because it had spread throughout the country. The national government had to withdraw from whole areas because the local people had taken over. That is when the Soviets took action and moved their tanks into the country.

Did the movie Charlie Wilson’s War bear any relationship to reality?

There was a lot in the film that I identified with. The biggest and most celebrated victories of the Mujahideen were when they were able to shoot a helicopter or a jet out of the air. It was what they talked about all the time.

Eventually they got Stinger missiles that could seek and destroy Russian aircraft, which forced the planes to fly at a very high altitude. They could no longer come in low. In the beginning, they would be a couple hundred feet off the ground, sometimes as low as 300 feet. Sometimes they were so low and so close they would fill my lens making it hard to photograph them. They would swoop in at an angle and we would pray they wouldn’t see us and start strafing. For a while, they had complete control of the air.

One night we were in a barracks asleep and they made a bombing run. The bomb landed just a few hundred feet away. There was a huge explosion and it blew out the glass and window frames into the room covering us with dust and debris.

It was 10 o’clock at night and the room was pitch-black swirling dust and smoke and, my god, we thought we were dead.

How did you get your film out of the country?

I decided to cross into Afghanistan secretly without my passport because it was impossible to get an Afghan visa at that point. So I walked for two or three days to get to where the fighting was. After a stay of two or three weeks, I had to return to Pakistan but had to enter without an exit visa or an entry visa in my passport. In that kind of situation, the rules really don’t apply. I had a bulky camera bag and couldn’t very well hide the cameras, but I thought I could place the exposed film in strategic places on my body and keep unexposed dummy rolls in the camera bag. I hid the film I had actually shot in my clothing. I was dressed as an Afghan and I had to hope that nobody would realize I was a foreigner until I got to a certain point beyond the frontier.

I passed back and forth over the border many times over the years. I was arrested four times in Pakistan. One time I spent five days in jail. For the first few times this was all new to me and all new to the Pakistanis. From their point of view, they must have been wondering who I was. Was I a spy, a gunrunner, a drug trafficker? Maybe they called the embassy. Who knows how they check these things. As time went on, the people covering the story had sort of an unofficial permission to cross into Afghanistan without using our passports.

I have gone into Afghanistan 30 or 40 times over the years. Of course, there was always a risk. Having the right translator/fixer is the most important thing. I never told my driver in advance where I was going or how long I would be in the country. After being robbed at gunpoint a few times you develop a sort of paranoia. One time my wallet was stolen at gunpoint. Another time I was behind the wheel driving down the road and there was a group of seven armed men pretending to be manning an official checkpoint. I had been through a lot of checkpoints so I knew what a real one looked like, and I had a very bad feeling about that one. So I just sped up and took off. They started firing their guns. As we drove off, a bus came right up behind me and shielded the field of vision between those shooters and our car. I stopped at the next checkpoint, a legitimate one, five or ten miles down the road, and when the bus driver came up, he said the bus had been hit by the bullets. I knew if I had stopped they would have stolen our money and cameras at the least, and maybe killed us.

At what point did you start working for National Geographic, which published several of your most important stories?

I went into Afghanistan with the Mujahideen in June of 1979. The New York Times ran a couple of my pictures, but nobody was terribly interested in the story. When the Russians invaded it became a huge story. My pictures started being published in newspapers and magazines around the world.

After being away for two years, I came back to the States in February of 1980. National Geographic had seen the pictures and was interested in doing a story in that region and they thought that I had access to certain areas, so they gave me an assignment to go to Pakistan to do a story on the Kalash people. I was torn between working for the news magazines with their quick turnaround and doing longer, more in-depth stories that sometimes may take months to produce and may not be published for a year or so.

Then I proposed two stories back-to-back to National Geographic, both of which were published. One was on the monsoon and one was on a train journey across South Asia from the Khyber Pass through India to Bangladesh. I had read the book The Great Railway Bazaar by Paul Theroux while I was flat on my back with dysentery. I loved that book. I thought it would be a wonderful picture story, so I ended up photographing it for National Geographic. Paul wrote the text that we parlayed into a book called The Imperial Way.

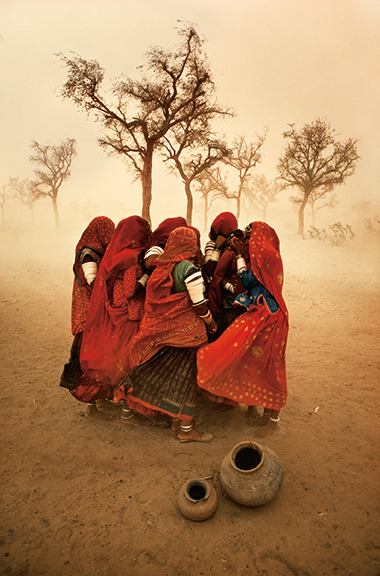

The monsoon story was about the renewal of life. If the monsoon fails, it’s life threatening, and if there’s too much rain there’s the danger of flooding. The monsoon is an important part of the Indian psyche. I thought that story was enormously important. I had always remembered the wonderful work of Brian Brake, a Magnum photographer who had photographed the monsoon back in the early sixties.

I spent most of 1984 photographing the monsoon and the train story, and on the heels of that, there was the Afghan border story in which I photographed Afghan refugees along the Afghan/Pakistan border. So these three stories came out one after the other.

The Afghan border story is the one in which the famous picture of the Afghan girl with green eyes appeared. How did you come to make that photograph?

In 1984 I was in Pakistan, outside of Peshawar, in an Afghan refugee camp. There were tens of thousands of tents. I walked past one particular tent that was being used as a girls’ school. I looked into the tent and asked the teacher if I could take some pictures and she agreed. It’s very difficult to photograph females in Afghan culture, and I thought maybe one way to deal with the problem would be to photograph young girls, which is usually all right.

You can photograph girls, but not grown women, with the exception of women in professional capacities like teachers and nurses. I picked out three young girls in the class, but I could see that one girl, whose name I learned years later was Sharbat Gula, had a really intense, haunted look, a penetrating gaze. She was about 12 years old. She was very shy, and I thought if I photographed the others first she would be more likely to agree because at some point she would not want to be left out.

There must have been about 15 girls in that school. They were all very young and they were doing what school children do all over the world. They were running around making noise and stirring up a lot of dust, but in that photograph for one brief moment you don’t hear the noise or all the kids running around and you don’t see all the dust. I guess she was as curious about me as I was about her because she had never met a foreigner and had never been photographed and had probably never seen a camera. So this was a new experience for her. Then, after a few moments, she just got up and walked away. She had run out of patience and her curiosity was satisfied. However, for a magical moment, all the elements had come into alignment. The background was right. The light was right. The emotion was right.

There’s a balance in the photograph. Even if you don’t know she’s an Afghan refugee, it’s clear that she’s a poor girl: she’s a little dirty, she has a hole in her shawl, but she is striking. There’s a mix of emotions and there’s a genuine quality about her. There is an ambiguity to her expression, a certain something or quality to that picture that people respond to.

Many people think that photograph has achieved the status of Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother photograph as one of the major iconic images of the 20th century.

It is amazing to me that this picture is known all over the world. Every day we get emails from people who want to reproduce it for unlikely purposes. I got an email from Tokyo, from a man who wants to use the Afghan girl photograph on a limited-edition bottle of sake. Part of the proceeds would go to a charity. We had to decline because it wouldn’t be appropriate. It’s such a strange request, but every day we get requests from people who want her picture for a textbook or an ad or who want to contact her to send her money.

Years later you tried to find her. How did you go about that?

I had looked for her for many years to no avail. After the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States in 2001, we invaded Afghanistan and shortly afterwards I was scheduled to go over with a film crew to do a documentary. One aspect of the plan was to look for this Afghan girl, but originally that was not the only objective. We got to Pakistan to begin the documentary and we started looking for her in the same refugee camp where I had photographed her in 1984. It was scheduled to be demolished so we got there just in time. We started to come close to finding her, and suddenly the film took an entirely different turn and it became just about looking for her. We never did make it to Afghanistan.

In the refugee camp we had a lot of cooperation from the tribal elders. I think there was a certain buzz about our project, in a positive sense. We had a really wonderful fixer-translator who was very respected. He was from the same tribe. The tribal elders knew him, knew his credentials. We talked to hundreds of people in the camp where she had lived. There were rumors that she had died or been killed.

Finally one man remembered her as a girl and said, “I know where her brother lives.” That man was actually able to bring her and her husband to us from across the border in Afghanistan where she was living. Fortunately, Sharbat Gula’s husband was completely helpful and cooperative, so we could meet her, interview her, and photograph her 17 years later, and actually help her — compensate her financially for the picture we had used for all those years. But it was kind of a shock. I had this image of her as a 12-year-old girl. And then suddenly she walks in the door and it’s not a 12-year-old girl; it’s a woman of 30. But she’s lived a very hard life. People age quickly in that harsh climate, [with a] lack of hygiene and poor diet. She looks at least twenty years older than her real age. It was a shock to see her after all those years.

Had she ever seen the photograph of herself as a girl?

No, no, she had never seen the picture. Oddly, her husband worked near a shop that had her picture in the window. He had walked past it but had never connected to it, never looked at the picture.

Sharbat Gula is illiterate. When we told her that the picture had been published all over the world, she didn’t understand. Her parents had been killed. She had lived a very sequestered life and didn’t really have any contact with the world outside of her husband and children and in-laws and maybe a few friends in the neighborhood, so she could not really understand the concept of magazines and television.

She had never seen television?

I think she had probably seen it, but only in glimpses. There was no electricity in her small town in Afghanistan. Maybe when she went to a teashop in a nearby town with her husband, there was a television off in a corner and [she] may have watched it for a few minutes.

Later, our documentary In Search of the Afghan Girl was aired, and she actually watched her story on Pakistani television, so at that time it really sank in that this was a big deal. I think it was so important to Afghans because there was a sense that she had represented all Afghan refugees and the country itself in a positive way. Afghans are very proud of that picture. They feel that it really shows courage and all those qualities of perseverance and pride and dignity. I’ve met Afghans all around Afghanistan and refugees in Washington D.C. and New York who have thanked me for the picture. Actually, Afghan Airlines used that picture on their airplane ticket coupon folder. It’s really turned out to be a good situation for her and her family. They were given an all-expense paid trip to Mecca for the Hajj, which was her life-long dream. Without this picture that would never have happened. She received compensation from National Geographic. Suddenly, based on a fleeting moment when you are 12 years old, this great thing happens to you. I don’t think her neighbors realize who she is — well, they don’t meet her for one thing — she lives a very quiet and secluded life.

How many stories have you done for National Geographic over the years and how many covers have you had?

I’ve had almost one article a year since the early ’80s. It’s great to have the cover of a magazine on the newsstands, but it’s better to have the long view. It’s more important to create a picture that survives in our consciousness and for some reason strikes a chord in our being. The amount of magazine work you do or the number of covers you have isn’t really the goal. In the end all that matters is, do we love that picture? Is it a picture we want to come back to time and time again?

One of your stories for National Geographic was on the first Gulf War in Iraq, Desert Storm, in 1991. What was the experience like to photograph that war?

Well, the story was really about the environmental impact of the hundreds of oil wells set burning in Kuwait by Saddam Hussein. I had actually gone over to that area a week or two prior to the ground offensive. Nobody knew when the ground war was going to start, but everybody knew there was going to be one. I started in Saudi Arabia photographing the oil coming up on the beaches. I joined an army unit and we went in the day the ground war began. It lasted only for about two days. It was very uneventful because there was no resistance. I spent the next three weeks photographing the damaged country of Kuwait. Not only were the oil fields on fire, but the Iraqi soldiers had also looted and vandalized everything. It was a very damaged country, but my main focus was on the environment.

It was absolutely one of the most amazing things to witness. It was really like this enormous End of the World movie set where you have all these overturned cars, destroyed buildings, and smoke in the sky. You didn’t see anybody on the roads for miles and miles. The oil fields were completely empty but occasionally you’d see camels. The middle of the oil field was so dark with smoke that it was like night, even though it was 11 o’clock in the morning. The smoke was black, the ground was black, and the camels were black. I was trying to find a way to separate the black camels from the black smoke. Suddenly they ran in front of an area of fire and they were in silhouette, so I was able to take a couple pictures.

The poor creatures were lost and they were caught in the middle of the conflagration. There were dead bodies all over the place. The Iraqis had fortified Kuwait, planning to hold it, so they mined the beaches. Within the first hours of the ground war, the Iraqis realized there was no chance and so they made a run for it back to Iraq. There was no water [and] no food, and hundreds of oil wells were on fire. No one knew what this meant, environmentally. Was it a catastrophic event for the whole planet? Of course all the marine life and bird life was affected, and then of course, the Gulf, where a lot of the oil comes from, was a big question. I really felt I was a witness to part of an historic event.

In your work, you have obviously faced many dangerous situations. What are some of the most memorable?

One of the scariest was a plane crash. I had hired a small, ultra-light, two-seater airplane in Yugoslavia to do aerials. The pilot flew down to the surface of the lake, very, very close — in fact so close that I told him to go up because we were about five feet from the water. If I wanted to be that close I could have hired a boat. But it was too late. The wheels got caught in the water and we couldn’t pull out.

We went down and as soon as the fuselage and the propeller hit the water, the propeller blew apart. Then we flipped upside down in this freezing alpine lake in the middle of February and immediately began to sink. The cockpit was not enclosed. The seatbelt was sort of homemade and I hadn’t studied it and couldn’t get it off. I realized I was going to die. I guess that part of your brain concerned with self-preservation kicked in and I slid underneath the seatbelt, literally went underneath, and was able to swim to the surface. The pilot made it, but didn’t attempt to help me.

There was another airplane incident in Africa. We got lost flying from Timbuktu in Mali back to the capital of Bamako. We left in a sandstorm and started flying along the Niger River. I guess the pilot’s navigational instruments weren’t working. He literally could not find his way back to the capital. I saw this guy circling and I thought, why are we circling? He came back down through the clouds. It was getting dark and there was a huge thunderstorm right in our path.

We were getting lower and lower and lower and then I realized we were going down. In the middle of nowhere he started to put the plane down in a field. I thought, oh, man, we’re going to hit a stone or a hole and crash. So we were bouncing along in this field alongside a big hole, and miraculously we came to a stop. We actually walked out and hired a jeep from a nearby village. We survived, but it gets you nervous.

Another time I was in India photographing the Chaturthi festival of Ganesh, the elephant god in the Hindu religion. For many days people celebrate by carrying a statue of Ganesh on their heads into the Indian Ocean. It is a sign of respect. On the final day there must be two million people taking part in this festival. I walked into the ocean to photograph as the men carrying this image of the elephant god went into the sea, and suddenly a group of boys — teenagers — ran up to me and start beating me. The water was already past my waist. Then they grabbed the camera strap and pulled it down so my head went under water; of course, then the camera was ruined. Totally destroyed.

My assistant, who had the rest of my camera equipment, was also there. They knocked him over. Everything was instantly ruined in the saltwater. Then, after getting my cameras underwater, they started thrashing me again. I thought they were going to drown me, once they got going. There were a half-dozen boys and each one is going to take his turn and the cumulative effect is that I’m going to drown. Once that mob mentality starts rolling sometimes it’s hard to stop it.

I had had that really bad experience with the water in Yugoslavia and as a child I had almost drowned a couple times playing in the streams in the wooded area near our house, so I had a fear of drowning. At the last minute, a man came up and intervened — saved me — called those guys off, and said I hadn’t done anything wrong. They may have feared that my presence would bring misfortune.

Why do you like working in Asia so much?

It’s impossible to find a place that has more diversity and a more disparate cultural situation. Imagine the proximity of Afghanistan, India, and Tibet, and yet they are so vastly different. You have all this conservative Islamic culture with Pakistan and its northwest frontier. Then you have —it’s just a day away, less than a day if you’re on a good road — millions of Hindus, embedded in a very strong, ancient culture.

Then there is a short jog up to Tibet, with its profound Buddhist culture and this incredible Himalayan landscape. I love the mountains and for me the Himalayas are the most dramatic and the most beautiful and breathtaking place I’ve ever been. Then you get down to broader Southeast Asia with Angkor Wat.

You have a wonderful, architectural range in Southeast Asia, as well as all the different kinds of religions and faiths and practices. The Jains, the Sikhs, the Muslims. India has one of the largest Muslim populations in the world, and there’s a huge Christian population. The Parsis are very interesting, a small Zoroastrian group centered around Bombay and Gujarat. There are temples and practices and festivals that are connected to these different religions. You have the forces of China, India, Buddhism, and Islam, all converging.

The politics involve tremendous intrigue. You have Afghanistan and Pakistan and Tibet. There is a lot of upheaval and churning. When I started out the Khmer Rouge was still active in Cambodia and Burma still had 20 insurgent groups active. Bangladesh was still a new country. Tibet was coming out of the dark ages of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, and Ceylon had become Sri Lanka with the Tamal Tigers. You have this dramatic weather system called the monsoon. The land is either flooding or in a drought.

Everywhere you turn there is something extraordinary happening, or terrible, or hideous, or beautiful, or sublime, or something which you have never seen before. After growing up in suburban Philadelphia, I found this to be a completely different experience.

Out of all of the different cities and countries you’ve visited throughout the years, would you be able to pick a favorite?

I guess I’d have to say my favorite countries are the Buddhist countries, whether it be Laos or Thailand or Cambodia or Bhutan or Tibet or Burma. Buddhism is endlessly fascinating — the iconography, the way the monks live. Their philosophy emphasizes compassion and non-violence. I guess Tibet is another one of my favorite places. Just to walk through those mountains and to visit the monasteries…it really speaks to me. I’m inspired to work there and to photograph there. It’s important to document this place because it’s a vanishing culture. Let’s celebrate it, let’s remember it, let’s somehow have a record of this before it’s lost forever. So many treasures of the world have been lost, so much beauty and knowledge.

The sad thing about Tibet is that the Chinese decided that they own it, so there was a struggle and an invasion and an occupation. You have over a billion Chinese population who could just overwhelm Tibet in a heartbeat. In fact they’ve already overwhelmed Tibet just in terms of sheer numbers. Take Lhasa for instance, the capital of Tibet, which is really more of a Chinese city than a Tibetan city. Probably 60–65 percent of Lhasa is Chinese now, so Tibetans are becoming strangers in their own land, second-class citizens in their own country. It’s just so sad to me to see this fragile culture in danger, in peril of being lost.

How do you approach an assignment? What research do you do beforehand?

Most of my photographic projects now involve places I’ve already been to and really experienced. With the monsoon in India, I had already been experiencing it, actually living it, for two or three years.

I did a story recently on the Bamiyan region in Afghanistan, the home of the Hazara tribe, a Mongolian people who came to Afghanistan perhaps a thousand years ago. They are a very peaceful, long-suffering tribe, who somehow end up on the short end of the stick. I’d already spent years observing them and living among them. So, as far as research goes, I want to arrive at a place with a pretty good idea of what I’m going to do. But there’s no point, really, in spending time trying to come up with a bunch of pre-conceived ideas because you will always end up being disappointed. I usually get to a place and immerse myself in the situation and then go from there. Since I’ve been so many places I have a long list of situations and places and people that I would love to photograph. Increasingly I am going independently to photograph whatever I want. Since I’ve always been interested in photographing Afghanistan, South Asia, Tibet, and Buddhism, it’s like a continuum rather than an assignment. I might get an assignment, but it’s really adding to my body of work.

You are especially noted for the powerful use of color. How do you think about color when you’re making a picture?

I thinkthere has to be a kind of a flow and a balance not only of color but also of composition. There’s a point at which things make sense and come to rest. Pictures hopefully are about something. I think the works of art that resonate with people — the ones that are the most successful — have some emotional component, some human story that we respond to. In the statue of David by Michelangelo or in the painting of Mona Lisa by da Vinci or in many of van Gogh’s or Rembrandt’s paintings, there’s something going on. But to get back to color, I think there’s a balance between having something completely monochromatic and having an excess of color. Often you need just two or three colors. You have to edit yourself as you shoot.

I think black-and-white is easier because you don’t have that extra problem of color to solve. A red bucket in the background can spoil a color picture. A red bucket in a black-and-white photograph is just a gray object. Honestly, I’m not looking for color pictures most of the time. I’m looking for something interesting, a little story, some humanity. Color is secondary. I’ll recognize it when I see it, but I’m not searching for a red thing here and another red thing over there. That doesn’t interest me as much as humanity and the human condition.

Do you photograph in black-and-white at all anymore?

Actually, I’m shooting a black-and-white project right now. I’m finding it’s a lot of fun. I’m not shooting it any differently than I shoot in color, so I think a lot of the discussion about how people photograph differently in black-and-white versus color is a lot of bunk.

Some people have a natural sense of design, a natural sense of balance, a natural sense of color. Henri Cartier-Bresson had a wonderful sense of design, of geometry, which he talked about. Well, he was a genius and he had a great gift.

Do you see a distinction between “photojournalism” and what might be called “documentary” photography?

I see myself as a documentary photographer, photographing the world as it is.

Do you think that the art world has been neglecting photojournalism and documentary photography?

I think some documentary photography is becoming more and more accepted in the fine art market.

There are certain documentary photographs in the world that just hit on something that we all respond to; there is a universal chord that speaks to us. They become important. Documents are important, and they rise to the surface in that world of collecting and exhibitions and people want them. Some of the photographers in the past — W. Eugene Smith, Dorothea Lange, Henri Cartier-Bresson — have been a bridge to acceptance of the documentary photographer in the art world today.

Do you sell your photographic prints and do you work with art galleries?

Yes, I sell my prints through my web site and also through galleries in the U.S. and Europe. I’m a member of Magnum Photos, and we have an exhibition division. I make Cibachrome prints for sale in the fine art market. Most of the prints are 20 x 24-inches, which is my favorite size. I go up to 30 x 40-inches. That’s usually the largest size. I work with a 35mm [camera], often in low light with things that are moving; sometimes there’s a limit to how large I can make a print.

How do you find the art scene? The photography art scene, specifically?

Well, I often look at work and wonder how we will perceive this in fifty years. What is compelling about this particular picture? Where is it taking me? Sometimes it just seems like the photographer is desperate to come up with a new idea to make a mark. It looks like too much effort went into trying to make “art.” I love the work of André Kertész and Dorothea Lange — mostly black-and-white photography, actually — and Cartier-Bresson. I think Ernst Haas was a brilliant color photographer. I want to look at a picture like Diane Arbus’s photograph of a boy in Central Park with a hand grenade. That’s powerful. There’s something amazing going on in that picture. I can think of several of Garry Winogrand’s pictures that really take you somewhere. He has a picture of a man in a wheelchair and two women are walking by and it’s just amazing. You look at those two sexy, attractive women walking by the man in a wheelchair. Two different worlds juxtaposed like that.

What projects are you working on now?

I’m working on a book about Southeast Asia and have some other interesting projects that keep me busy.

You are known for your interest in humanitarian projects. What are some of the ones you’ve been involved with?

I have worked with other Magnum photographers for The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. In 2007, The Global Fund initiated a joint project with Magnum, to document the positive impact that free antiretroviral drug treatment is having on the lives of millions of HIV-positive and AIDS patients around the world.

We picked subjects who had just started the treatment and then we went back four months later to see how the treatment was impacting the disease. If the people follow the regimen they can resume a normal life, unless they are already too advanced. We want to bring attention to this program because something like 30 million people in the world have AIDS. When you see how it affects peoples’ lives…obviously there’s the human, emotional component. But there’s also the economic component.

If one of the parents gets AIDS and dies, usually the father, then the mother is left to raise the children and to try to make a living, and perhaps she has contracted AIDS, too. I was just down in Washington, D.C., for the opening of the show, called Access to Life, at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, where the exhibition is appearing June–July, 2008. The exhibition will travel to major cities around the world during 2008 and 2009. There are online video pieces and a book will be published.

On my web site I have an appeal for Imagineasia. I started this nonprofit endeavor with family and friends. It’s a simple attempt to get textbooks, pencils, and notebooks to the Bamiyan region of Afghanistan, where the Hazara people live. This region is particularly neglected. The idea is that we can do something simple, something direct, that gets supplies and money directly to the people. You know, it’s a fortunate thing that as an artist or a photographer, you can always donate your work for a charitable cause. I think it’s one of the important functions of photography to draw attention to problems and then to see if we can educate people so that it might motivate them to want to make the world a better place. One of the journals of philanthropy stated that the picture of the Afghan Girl had raised more money than any other picture. That is gratifying.

There is a strong emphasis on portraiture in your work. Why is that so important to you?

As human beings we are all fascinated with each other and how we look. Diane Arbus talked about the gap between intention and effect in portraiture. People put on make-up and adorn themselves because they want to create an effect and give a certain impression, but often other people look at them and say it’s tragic or comical or curious or funny or odd. Arbus photographed a woman on Park Avenue trying to make a statement with her appearance, but in fact we see through it, we see the folly. Portraiture can be that kind of sharp critique. We go to another culture to observe how other people live. Sometimes you look at somebody on the street and they just seem to have a strong presence, a look, a certain kind of attribute that comes out in the face.

In Tibet, for instance, where people have such a great sense of style, an innate fashion sense, they come out of the mountains wearing these outlandish hats, make-up, jewelry in their hair. The Jains in India have exalted and highly revered monks who are naked because they consider the sky to be their garment. They are detached from material things and being naked is a symbol of their renunciation. The nuns and monks wear masks to ensure that no germs or insects creep in. How did they arrive at that, as opposed to Islam where they go to the other end of the spectrum to be covered in flowing robes? I’ve learned that humor is universal. You do a little bit of mime and people laugh. It’s very easy to use humor to connect to people in any culture. Part of what I’ve done is to wander and observe the world. What else is more interesting that that? Sometimes I think it’s good to observe our planet as though we were dropped down here to make a field report on Planet Earth.

For more information visit www.stevemccurry.com Steve McCurry’s work will be on exhibition at the Open Shutter Gallery August 21st – October 1st, 2009. For more information you can visit their website at www.openshuttergallery.com or call 970.382.8355.

Jain Kelly was the assistant director of The Witkin Gallery in New York during the 1970s. She is an author, appraiser, and fine-art photography advisor. She edited Darkroom 2 (Lustrum Press, 1978) and Nude: Theory (Lustrum Press, 1979). She was the photo researcher for A World History of Photography by Dr. Naomi Rosenblum (Abbeville Press, 1984) and the author of the biographical section of A History of Women Photographers by Dr. Rosenblum (Abbeville Press, 1994). She has written articles for Art in America and Popular Photography. Her E-Mail is [email protected].

You may like

-

Cara Barer’s ‘Bibliomania’: A Captivating Exploration of the Transitory Nature of Books

-

Exploring Douglass’s Legacy: Isaac Julien’s “Lessons of the Hour” at MoMA

-

Between Dreams and Reality: The Surreal Artistry of Miss Aniela (Natalie Dybisz)

-

Focus Fine Art Photography Magazine Statement on the Passing of Elliott Erwitt

-

REVIEW: Play the Part: Marlene Dietrich

-

Through the Lens of Tragedy: The Final Frames of Gilad Kfir, Photographer and Aspiring Father