Behind the Lens

An Outsider on the Inside: Bruce Davidson

Published

1 year agoon

By

Jain Kelly

Bruce Davidson is known as an artist whose work ethic is unusually consistent. He invests a great deal of thought in his projects before he begins, but that is only half the equation. The other half is sheer, non-stop work over extended periods of time to accomplish his goals. His approach requires an extreme level of organization, right down to the careful filing of prints. He brings that same work ethic and organizational ability to the presentation of his exhibitions in the art world. Although a veteran of the museum world — his first one-person show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York took place over 40 years ago, in 1963 — he has come to the art gallery scene relatively recently, in the 1980s. In a short period of time he has emerged as an important figure in the collectibles market, partly because his body of work is large enough to sustain exhibition after exhibition in rapid succession. It is notable that in addition to investing time in preparing exhibitions and arranging his archive of past work, he still moves forward with the act of photographing the present and planning future projects with joyful intensity.

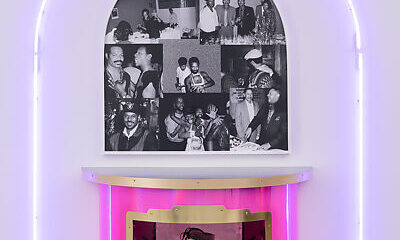

At the time of this interview, The Jewish Museum in New York City is presenting Isaac Bashevis Singer and the Lower East Side: Photographs by Bruce Davidson.

Spanning the years 1957 to 1990, the exhibition features 40 intimate photographs of Singer, the revered Yiddish author, as well as residents of the Lower East Side Jewish community, including visitors to the Garden Cafeteria in that location. Could you tell us a little about your relationship to both Isaac Bashevis Singer and the world of the Lower East Side?

Isaac Bashevis Singer lived in our building here in New York on the fifth floor. I had photographed him years before on a magazine assignment. We just became neighbors. Also, I was interested in trying to find out about his world because that was the world of my grandfather. I wanted to find continuity. My grandfather came to the United States from Poland as a boy of 14. He learned English, became a tailor, and had a very good business. He went from being a tailor into manufacturing with his older son Leonard and Leonard’s wife Ruth, and that company is very large now.

I was born in 1933 and grew up in Oak Park, Illinois. My mother was a single parent. She was working in a torpedo factory during World War II. My brother and I could really fend for ourselves. We were very self-sufficient. We learned to cook. We learned to clean. We learned to meet our mother on time at the bus stop and carry home very heavy packages of groceries. My younger brother became an eminent scientist. I became a photographer. That was all part of being with my grandfather. For a while we lived with my grandfather in the home my mother was raised in. I began to sense there was something strange about my grandfather, there was some secret. There was something he left behind and he never really talked to us about it.

I was the first son in our family at that time to be Bar Mitzvahed. Our synagogue was a small clubhouse synagogue. I mean it was not a synagogue at all; it was a clubhouse with a small congregation. While I was reciting the Hav Torah during my Bar Mitzvah, I could see a box that I knew would be a camera on the rabbi’s desk. During the 1940s, cameras were scarce. Film was scarce. I had been taking pictures since the age of 10, and was very excited about receiving my first good camera and two rolls of film.

I was taking pictures and my grandmother emptied out a closet in the basement where she stored bottles of jelly. I began developing and making small contact prints in it. I even wrote on the outside of the jelly closet — I mean, it was small; I could barely fit in it — but I wrote “Bruce’s Photo Shop.”

You know, there is a similarity between photographing and tailoring. You learn to make the pockets straight, and actually you have the persona of the person you are fixing the jacket for. The persona is definitely there. It’s craft. And photography has craft also. So my grandfather sewed buttons and I sewed photographs. So I would say that entering the world of Singer and the Lower East Side was really entering the world of my grandfather, but I am in no way an observant Jew.

As a Midwesterner transplanted to New York, you have demonstrated your great love of the city and its inhabitants in many series of photographs. Could you expand on your feelings about New York and how the city inspires you?

The town of Oak Park was a very small community. It was the home of Frank Lloyd Wright and Ernest Hemingway. I have said that I am not a practicing Jew, but I am in the sense that wherever I photograph in New York — or wherever I photograph anywhere — it becomes to me a spiritual space in that I think there is a solemn responsibility when you have a camera.

Although I don’t read the Torah, I do read the Torah of life, and my own personal Torah, so it wasn’t a big deal to leave Illinois to come East, to go to school, and to explore New York. My very first day in New York — my mother had remarried and we were staying at the Plaza Hotel — I began to explore. I went outside the hotel and I was photographing the pigeons and people with my Rolleiflex. My mother or my stepfather came out and said, “You’re using up all your film.” I think New York is probably the most important and the most alive city in the world. It’s the most diverse. It’s the most difficult. It’s the most challenging.

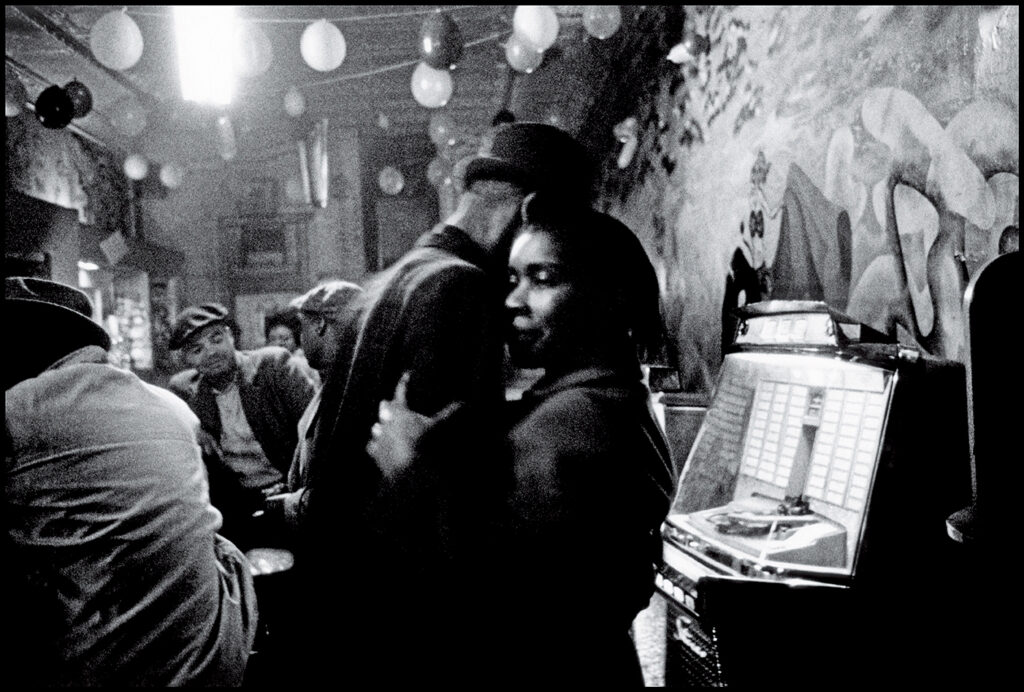

I have found that over the years I have been able to enter worlds within worlds in the city, beginning with the Circus series, then the Brooklyn Gang, and later the Subway and Central Park, and other entities. I entered worlds within worlds and they became sacred places for me. I no longer entered a shul; I entered the sacred space of people’s lives.

You have compared the New York City subway to the Theater of the Absurd. Do you still think of it this way?

Yes, but it is also the most democratic space in the world. Anybody, rich or poor, healthy or unhealthy, rides the subway. The graffiti at the time was written all over the place and was what is called the hieroglyphics of anxiety, of anger, of frustration, of “I am invisible but my marking remains.” You know, dogs pee on a pole but graffiti artists draw their name. The dog says, “This is me. I am here.” They’re making their marking and then somebody else comes over and pees on that marking and makes a new marking; so that was the dynamic. But the subway could be excruciatingly beautiful. It could be the sexiest environment I’ve ever been in; we can’t go into details but the subway can really be sexy.

How did all this relate to the mood of the city at that time?

At that time, about 1980, the trains were running poorly. They were very unsafe, there were a lot of muggers, there was graffiti written all over the place. I think the city was in default at that time, also. It was a chaotic, neurotic, pathetic time. And I chose…the subway really chose me. I started to go into it with a camera out, with a flash. A safari hunter. In fact I fashioned myself after the tiger hunter Jim Corbett. His books were written for boys but I liked them. So I became the tiger hunter. When you hunt tigers you have to watch your back. Anyway, I had all sorts of fantasies going because that’s what the subway can be. It could become as sacred as a church pew, it could be beautiful, it could be upsetting, it could be depressing. Anything goes, and I fed on that.

You have stated that your work in the subway was an antidote to depression. How was that so?

Because the subway was more depressed than I was. And in photographing in color — I wanted the color to be vibrant — I drew a parallel between fish in the deep sea where you see no light and yet you have iridescent colors when light is shown on them. I wanted to transform the subway in some way so that from a beast I made it beautiful and when it was beautiful I made it bestial, so that anything could come to me or reflect off me and rebound in the subway. I left my imagination and awareness open to the moment. The color experience was also a human experience.

Did you find it an experience of loneliness?

Yes, I seem to be attracted to things in transition, things that are isolated, maybe alone. I gravitate to that which has a certain tension because it’s in transition. The circus was in transition from tent shows to coliseum shows, from small, intimate family circuses to large extravaganzas.

Let’s talk about your circus photographs. Historically, many artists of the 20th century, such as Pablo Picasso, Alexander Calder and Walt Kuhn, have been drawn to clowns and the circus. What do you think is the source of the appeal and how did you yourself get started with the circus?

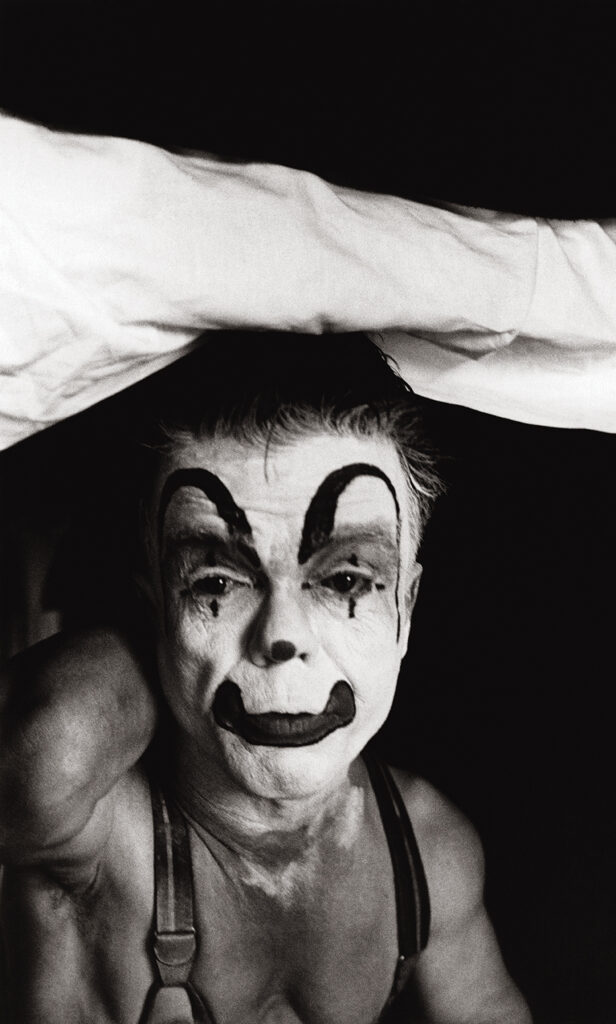

Magnum in New York had an incredible picture librarian by the name of Sam Holmes. Sam was an amateur trapeze artist. He was the one who told me about the circus in Palisades Amusement Park in New Jersey, which was the beginning of my circus work in 1958. I was not drawn to the circus per se, but to the clown who was a dwarf.

It was the combination of attraction and repulsion that I felt standing next to him outside the circus tent that drew my attention and sustained a friendship with him. His name was Jimmy Armstrong. He was melancholy. He was sensitive, very sensitive to everything. He wasn’t depressed but he was poetic. It’s almost like he was a performance artist. Even when he was outside the tent, he was performing; he was directing the camera to what he could feel at the time. I never said, ”Jimmy, why don’t you pick up your trumpet and blow it.” I waited for him to do it. He worked hard in the circus. He was carrying two heavy buckets of water. And you know, people in the circus liked him. I have a picture in the Circus book of a roustabout giving him a massage. He didn’t have to do that. But that was the nature of the circus, too — they were a family.

They were kind of like Magnum, but with elephants. Jimmy and I had a very silent friendship. I just observed him. He allowed me to observe. He also allowed me to see things that might have been embarrassing for him, or even dangerous, like walking through a crowd of children. You know children can be quite cruel to dwarves. Where else can you find someone with the same size head as your father, but half your size? At the end of our two-month trip together I bought him a Yashica Rolleiflex-type camera that he could hold in his hand. He often said that I was his best friend, even though I wasn’t really close to him, except in the sense that I was with him all the time. What made it so compelling was that we all have a dwarf in us, and that dwarf can come out in various ways: something small and compressed as being repulsive.

The picture I took of him peeking out of the van [on the cover of this issue] is an early ”confrontational” photograph. It isn’t that other photographers hadn’t done confrontational photographs, but it was something that wasn’t usually done. In photojournalism at that time you were supposed to be the “unobserved observer.” So no one looked at the camera because the camera wasn’t “there.” Here I made the camera “there.” I think that was a very penetrating thing.

The fact that Jimmy Armstrong, the clown, allowed me that close into his soul was important to me. He was married and had children. He married a normal-sized, but short, woman named Margie. Jimmy is dead now, and Sam and I can’t seem to find Margie. Sam found out that Jimmy, during World War II, could crawl into the fuselage of the bombers to do wiring. So he joined the war effort as a dwarf. He had a lot of lives. He was a musician. He was photographed by many different photographers, including André Kertész. He was even in a movie, Cecil B. DeMille’s The Greatest Show on Earth (1952) with Charlton Heston and Betty Hutton.

After I left the circus, he sent me a route card every once in a while. This was his schedule, so I knew where he would be. I would call the chief of police of a town and say, “My cousin is a dwarf in the circus. Could you get a message to him?” The chief would assume that I was a dwarf too, and he would jump into his car and run out with the message, “call me,” or whatever. Over time I lost track.

Going back to the period of your life following Yale, you were in the military from 1955 to 1957. Was there anything about that experience that relates to your photographic work?

Absolutely. In the army, I was in the Arizona desert for about a year. I used to hitchhike to Nogales, which was only 40 or 50 miles away, to photograph the bullfights. Patricia McCormick was a female bullfighter and I became somewhat friendly with her. In hitchhiking to Nogales I came upon a small town called Patagonia. It was really a railroad siding and a bar and a gas station and a post office and that was about it. There I met an old guy who was driving a Model T Ford and we became friendly. He was a miner.

Every weekend I stayed at his bunkhouse and photographed. As I look at that body of work now, it seems very whole to me and I find it amazing. It was the precursor to the Widow of Montmartre, which I made the following year, when I was transferred from Fort Huachuca, Arizona to Paris, France. There I met a French soldier who invited me to have lunch with him and his mother in Montmartre.

After lunch I was standing on the balcony with my Leica and I saw an elderly woman hobbling up the street. I took a picture. The soldier said, “Oh, that woman lives above us and in fact she knew Toulouse-Lautrec, Renoir and Gauguin.” She was in her 90s in 1956, you see. She was the widow of the Impressionist painter Leon Fauchet. So the soldier introduced us and that series became the Widow of Montmartre. I lost track of that soldier for many years, but recently found him. He still lives in the same area. He’s one of the painters at the top of the hill in Montmartre.

At that point in my life I decided to show my work to Magnum Photos in Paris and to Henri Cartier-Bresson. Well, actually I had no idea of Cartier-Bresson. He was beyond reach. I left my photos at the Magnum office. They called me and said, “We would like to show your work to Cartier-Bresson.” Then I had an appointment with him, and that was the beginning of my career, and my life in photography.

Henri Cartier-Bresson is known as one of the most influential photographers of the 20th century. What was the effect of Cartier-Bresson on you and your work?

Cartier-Bresson took me under his wing. He tried to get me to read more, to reflect more, to be more disciplined. Over that year we had a professional relationship in which I occasionally showed him my work. Of course he had seen the Widow of Montmartre contact sheets. In fact, I just donated those vintage contact sheets from 1956 and about 17 prints to the Fondation Cartier-Bresson in Paris.

Cartier-Bresson is known for developing the concept of the Decisive Moment, one definition of which is the moment of stillness at the peak of action. Do you see yourself as being influenced by this idea?

Well, the concept of the Decisive Moment has never been absolutely clear to me. To me it’s the Decisive Mood, and not the moment. I think that, sure, there is a decisive moment in life in everything we do. There’s a certain timing. But it isn’t just about timing, a man jumping over a puddle.

The Decisive Moment is an internal thing. If you become decisive and you enter life in a decisive way, the moments will appear, as long as you are in tune. So what we are really talking about is a way of looking at life, a kind of balance. Sure, there’s geometry, there are moments and all that, but my photographs are more of a mood and they are cumulative, too.

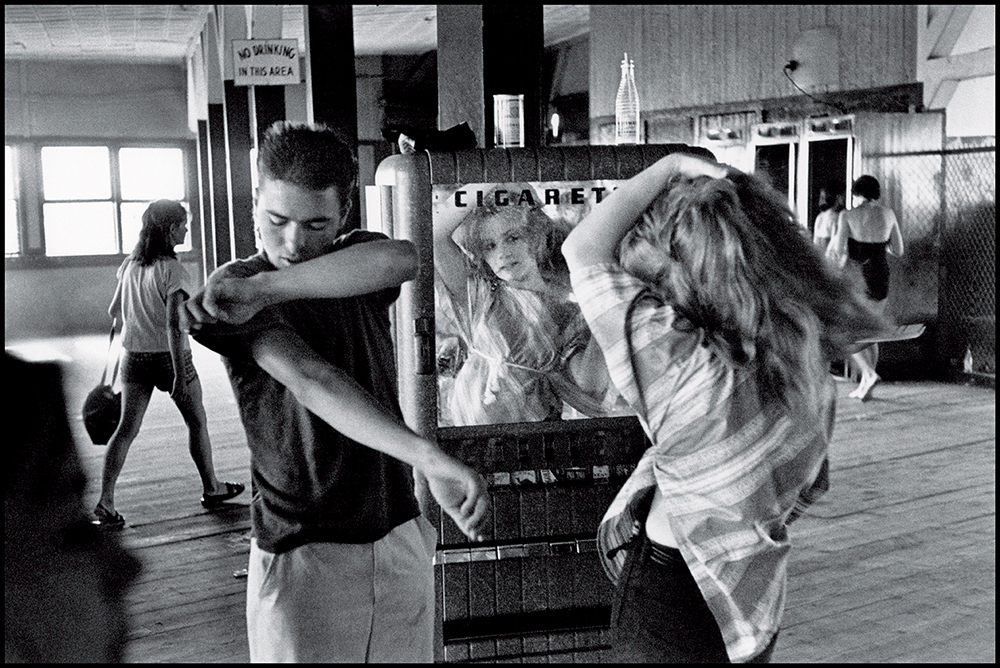

You did your series on the Brooklyn Gang in 1959. It was published in Esquire Magazine that year, but it did not appear in book form — Brooklyn Gang, published by Twin Palms — until 1998. One critic has described the essay on the Brooklyn Gang as having an air of innocence about it. Do you agree with that?

Those kids, at that time, you see, were actually abandoned by everybody, the church, the community, their families. Most of them were really poor. They weren’t living on the street, but they were living in dysfunctional homes. It’s the same thing.

Anyway, they were kids and the reason that body of work has survived is that it’s about emotion. That kind of mood and tension and sexual vitality, that’s what those pictures were really about. They weren’t about war. I mean, you can’t compare those kids to the kids today who have machine guns. So there is an innocence in the photographs because it reflected the kids’ innocence, but that innocence could erupt into violence. It’s interesting that the leader of the Brooklyn Gang, Bengie, who is now 65 years old, called when I was given a large show of the Brooklyn Gang at the International Center for Photography (ICP) in New York in 1998–99. My wife and I went down together and had coffee with him in midtown, and he turned out to have had an extraordinary life. He is now a substance abuse counselor. We just returned last Sunday from his birthday party, where we saw some of the old gang members.

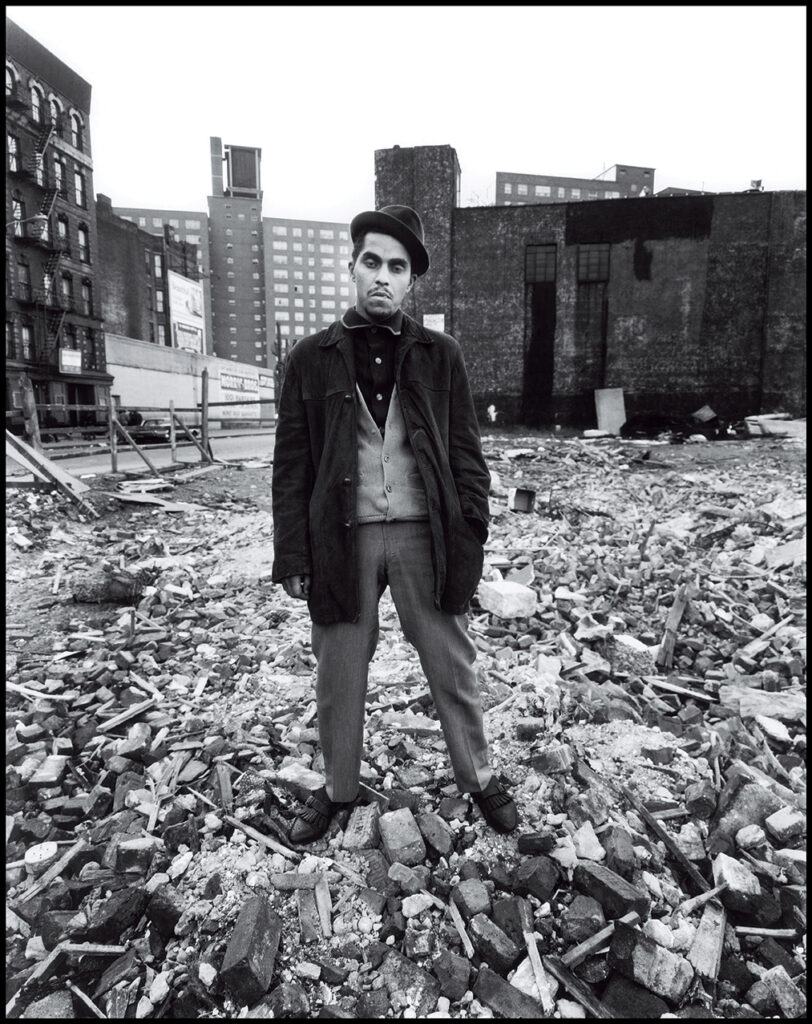

Perhaps we could discuss East 100th Street for a while. You photographed on that block from 1966 to 1968. The book East 100th Street was published by Harvard University Press in 1970, and was reissued in an expanded edition by St. Ann’s Press in 2003. You received the first-ever photography grant from the National Endowment of the Arts in 1966, which you used in support of the East 100th Street project. East 100th Street appeared as a solo exhibition — your second at this venue — at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1970. How did you come to be introduced to the people on East 100th Street?

Sam Holmes, the picture librarian at Magnum who told me about the circus in Palisades Amusement Park, also told me about the “worst block in Spanish Harlem.” His cousin was a minister living on the block and working with the Metro North Citizens’ Committee. So I looked up the minister and had an appointment with the Citizens’ Committee and then I photographed for two years.

Were you attempting to create collaboration between the photographer and the subject?

Yes, one of the reasons I chose to use what would be regarded as an old-fashioned view camera on a tripod, with a flash, was that I felt it dignified the act of photography. I was eye-to-eye, face-to-face with the subject. The only thing that connected me to a camera was the little cable release, but I was really looking into the eyes of my subject. The environment was also important; what surrounded them was part of the picture, too. It was part of their expression. If the wall had a picture on it or a birdcage or nothing, it said something about them.

In some of the photographs the people presented themselves in a middle class way, very dressed up. Why do you think they chose to do that?

Well, you know, people are middle class in their minds. They may not own an automobile, but they dress very elegantly on Sunday, going to church. I had an experience in which I saw some children half-naked. They just had some little panties on and they were playing on the fire escape.

I went to take that picture. The mother saw me and brought the kids in through the window. I counted the floors and went up and knocked on the door. The woman said, “You can photograph my children that way, but you must also photograph them dressed up.” So I photographed them playing on the fire escape and on Sunday I photographed the family dressed up.

Much has been made of the dark tonality of the photographs in East 100th Street. Did that tonality emerge immediately as your intention, or did it evolve over time?

When I entered a person’s home I was entering a sacred space, is the way I looked at it. It was up to the person to decide where the photograph might be made. Was it in the kitchen, in the bedroom, or in the vacant lot downstairs? Most of the time it was in the bedroom because it was a quiet space and it had artifacts or clues to their spirituality, like a cross, a picture of Jesus, a framed photograph of John F. Kennedy.

Very often these dwellings were dark. I remember a photograph I took of an elderly woman sitting on a bed with towels and rags stuck into the cracks in the window to keep out the cold air. That was an important part of the photograph, which showed her sitting alone in this dark room with only one little light bulb on the ceiling. I tried to be true to the mood, to the darkness, and through the darkness I made a light because I made an image of that person’s predicament in life. So when I printed the photographs for the book I printed them in a very strong and heavy way. In fact, I was inspired by the bronze Degas sculpture of dancers at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The bronze looked like shrapnel to me. It was dark, metallic, rich, and I followed that through as a theme in the printing of my photographs. I was highly impassioned in those days with that tonality.

Years later, when I was printing for the second edition of East 100th Street, I opened up the tonality because I was able to: the technology had improved. I had the aid of a scanner. I made the printing a little lighter. East 100th Street wasn’t just a documentation. It was a vision, a vision in which I reached into the tonality with a large format camera. I wanted that depth of field. I wanted to be able to see down to the street while someone was lying on the couch. The way the camera was used, the way the lighting was used, the way I saw things were all part of the aesthetic. The aesthetic dimension to East 100th Street combined with the sociological message.

How recently have you had contact with the people on the block?

A few years ago I received a fellowship from the Open Society to go back to photograph. When I returned I could find very few people I knew. They had moved on. You know, people move on. What happened in the 1960s was that a matrix of new schools, tutorial programs, all kinds of things, rippled all through Spanish Harlem. Metro North Association was the beginning of that self-improvement, reviving the community. The community itself was doing it. I photographed positive aspects of new schools, new housing, tutorial programs, a new park and ball field, a women’s health center, the vest pocket gardens, and the new mood and the street. I’ve donated all that work to the Union Settlement and it is on display there. Yes, Spanish Harlem has changed. It’s almost easier to get a caffe latte now than a café con leche. Some of the texture is lost, but it’s a lot safer than it was.

Obviously you maintain contact with people you have photographed over the years. Can you tell us more about that?

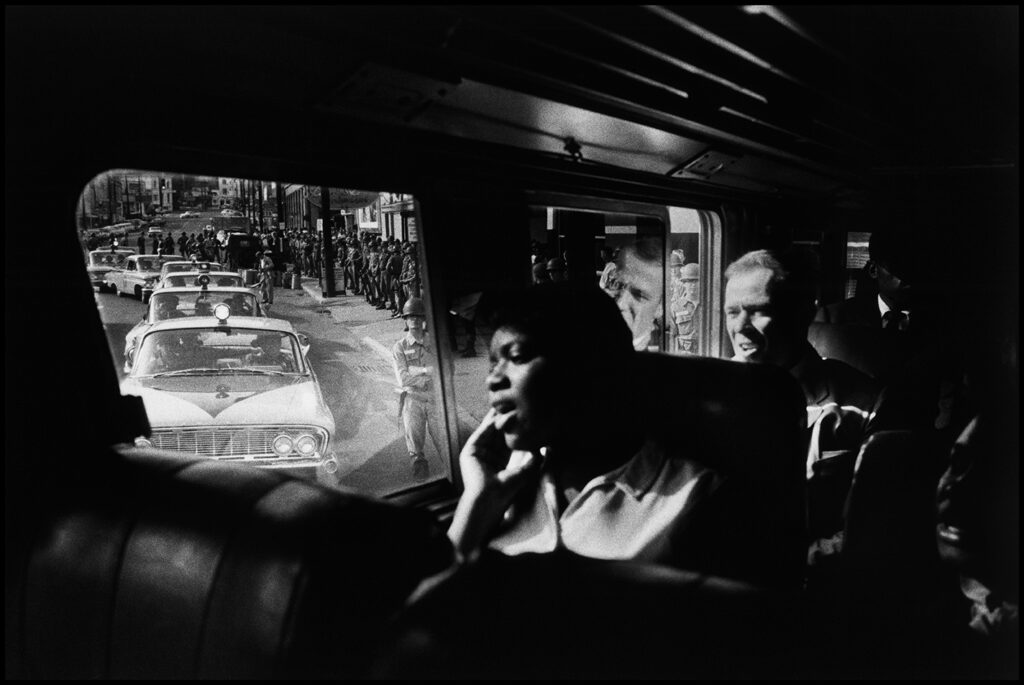

I do, but I don’t overdo it, because life goes on. In Time of Change, there is a picture of a woman in a shack holding a baby, made during the Selma march. I found that baby and I found the whole family recently and re-photographed them.

Their lives had changed tremendously because of the Voting Rights Act that allowed the younger children to get a better education. One of the 11 children holds a master’s degree in library science and became head legal librarian at the State Capitol in Montgomery, Alabama. Almost all of the younger children I photographed have successful lives.

You photographed the Civil Rights Movement, primarily in the American South, from 1961 to 1965. In 1962 you received a Guggenheim Fellowship in support of this project, and in 1963 the Museum of Modern Art included these historic images, among others, in a solo exhibition. The book, Time of Change, Civil Rights Photographs 1961–1965 was published by St. Ann’s Press in 2002. In that same year, the International Center for Photography presented an exhibition of Time of Change. When you were photographing these events in the early ’60s, did you find it a frightening experience?

Oh, yes, because if you made a mistake and you got into a situation that you couldn’t get out of…that almost happened to me. I photographed a Ku Klux Klan meeting, but I drove my little Volkswagen bug too close to the cross.

When they lit it, they said, “New York license plate so-and-so, you’re too close to the fire.” I knew that that was not going to be cool, to have New York license plates at a Klan meeting in Georgia. I stayed a while, took a few pictures, and then left.

Would you call the Civil Rights photographs a turning point in your life?

Well, it certainly made it possible for me to understand what I was getting into in East 100th Street. It was the prelude to East 100th Street. It was like my homework. I had borne witness to what was going on in the South and to some extent become sensitized to what was happening in the North, too. Without that background I don’t think I would have done East 100th Street the way I did.

What about your early fashion days? How did that happen?

The story I heard was that after Brooklyn Gang was published, Alex Lieberman, the creative director of Vogue Magazine, was having lunch with Cartier-Bresson. He asked Bresson if he thought the young Bruce Davidson could do fashion. Bresson’s answer was: “If he can do gangs, why can’t he do fashion? What’s the difference?”

So I did a lot of fashion for about three years. I rarely do fashion now. I came to a point in the Civil Rights Movement where I was doing fashion and also protest marches and I couldn’t equate the two things, so I gave up fashion. I’m good at fashion photography but it doesn’t give me meaning. It’s like cotton candy. It looks beautiful, but it melts in your mouth, and the sugar can rot your teeth.

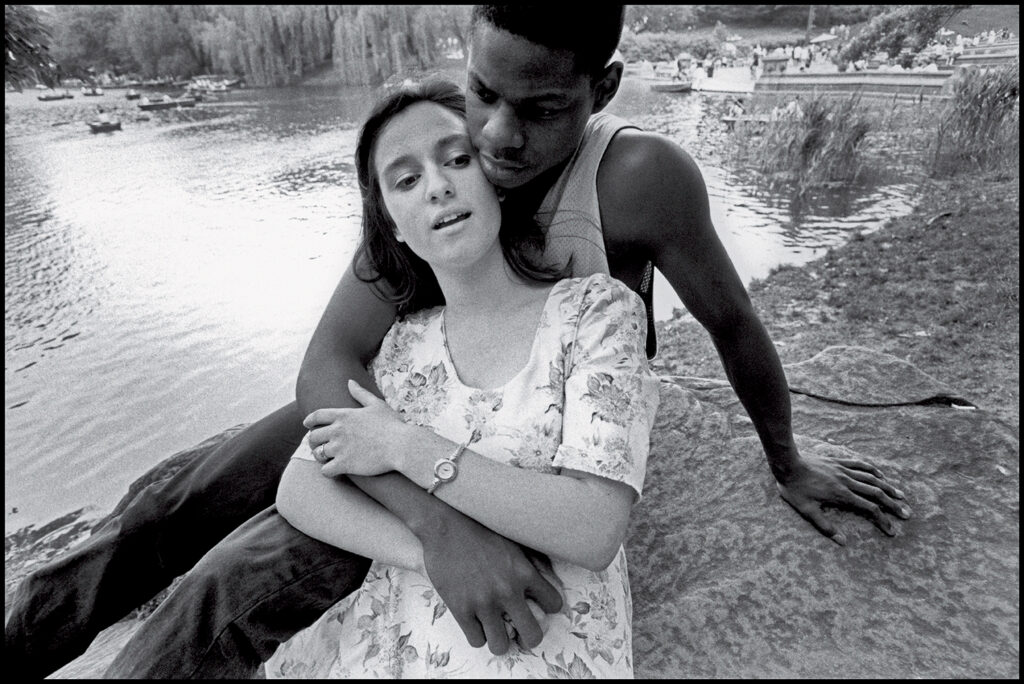

During the early 1990s, you did an extensive series on Central Park here in New York, which culminated in the book Central Park, published by Aperture Press in 1995. How did that series come about?

I did a body of work for National Geographic Magazine called The Neighborhood, in which I retraced my boyhood steps in the Chicago area. After I completed that the editors asked me what else I would like to do. I said I’ll make a list of ten things. To make it an even ten, I added Central Park. We used to take the kids there and at that time it was like a dust bowl. You never knew when you were sitting with your children if there were hypodermic needles sticking them.

Then the editors said, “Oh, Central Park, that’s a good idea.” I said, “I need four seasons and I need to be in black-and-white.” They said, “Oh, no, we are a color magazine. You have to do it in color and we can give you only three seasons.” So I went out and I started photographing Central Park. I exposed 500 rolls of film. Then we had a presentation. The next morning I got a call from the editor-in-chief Bill Graves, who said, “We’re pulling the plug on this project. Think of something else.” So I said to myself, “Good, I’m free at last,” and I went back to Central Park with my Canon Cameras and I spent the next three years photographing in black-and-white.

What are you interested in photographing at present?

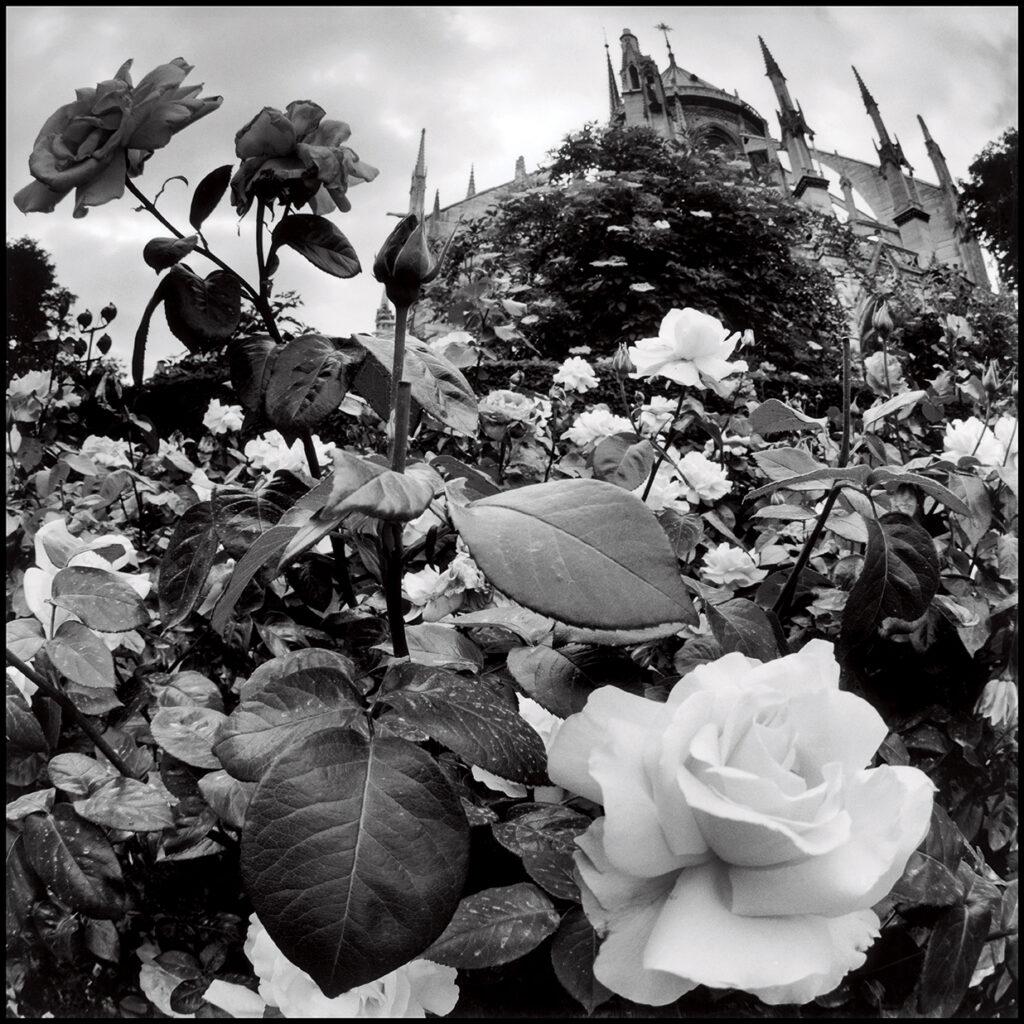

I’m interested in the balance of nature right now and the meaning of the vegetation that at times goes unnoticed in our lives. I just finished a large body of work called the Nature of Paris. It was shown at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris.

The exhibition opened in June of 2007 and closed in September. In Paris I think I made an homage to vegetation. In that city the monuments take over. We go to the Eiffel Tower and we don’t realize there’s a 500-year-old tree growing right next to it. When you see the pictures it will be self-evident. I’m interested in raising people’s consciousness, my own included, to the meaning and the need for green space and vegetation. When I began the project in Paris, I began by photographing some people in nature. For instance, my assistant found an elderly woman in the cemetery in Montmartre, a woman well into her 80s or 90s. There were cats standing on the tombstones, waiting for her to come to them with food. They wouldn’t just rush in. I photographed her and also lovers in the park and all that kind of stuff, and I was getting sick from it. I edited it all out, including the panoramas, even though the panoramas were successful, I thought. I edited all the 35mm pictures out. There was something I was doing with the square format that was coming through to me. In the end the whole show was nothing but the Hasselblad 2 ¼” photographs. I was able to disinvest all that other imagery, which I’d already done, into something that I hadn’t done, something that was new to me, fresh to me. And challenging. I’m looking for another city that would be the extension of Central Park and Nature of Paris. I would like to continue the concept that was born through the Paris photographs.

At what point did you become interested in selling your photographic prints through galleries?

I was too busy photographing during the 1970s to become affiliated with a gallery. I became interested in the 1980s. It was Howard Greenberg who really brought me out of the fine art world “shadows” and into the sunshine. I had my first exhibition with his gallery in New York in 2002. I felt that Howard could really embrace my work and he did. Howard is, as they say in Yiddish, meshpokha, he’s family.

He understands the work, he’s honest, he’s energetic, and he assigned me Nancy Lieberman, who is wonderful, and who manages my work for the gallery. Recently she arranged for my wife and me to go to Greece for a 75-print commemorative exhibition for the Hellenic-American Institute in Athens.

Sandra Berler in Chevy Chase, Maryland is my sister-in-law and has represented me and others for over thirty-five years. In addition to owning a fine gallery, she is an excellent art historian and writer. Recently she arranged a show of my work along with a lecture at Sidwell Friends, the well-known school in Washington, D.C. This was a very successful experience.

On the West Coast, Rose Shoshana and Laura Peterson of the Rose Gallery have mounted some of the most beautiful exhibitions I’ve ever had. They did a dye transfer color show of Subway that was amazing to see, and before that, Brooklyn Gang. They had a patron who underwrote the creation of a portfolio of Subway containing 47 very large dye transfer prints (20 x 24″) in an edition of 7. I think there are only two portfolios left.

I am now working with three people: Howard Greenberg Gallery, in New York, Rose Gallery in Santa Monica, California and the Sandra Berler Gallery in Chevy Chase, Maryland.

After 9/11, did you have a desire to photograph events here in New York City?

Well, I went down a night or two to 9/11 to photograph. It was very difficult to get permission to work. I had sent a whole portfolio of photographs — not of 9/11 — to Hillary Clinton, but it never got to her.

The FBI just X-rayed things and kept them, so I got those prints back a year later. So I didn’t have permission to get down there, but I knew someone who operated a building nearby and they were housing police overnight. He said the captain would be willing to take me around for a while at night, but that was all I could get.

In my slide presentation I have a photograph of the Twin Towers at night with the Statue of Liberty before 9/11. It’s a photograph that can be taken only with a 1700mm telephoto lens. There are only two in the world. I borrowed it from Canon. My wife did the scouting. She found a pier that jutted out a quarter of a mile into the bay.

It’s a Kodachrome picture of the World Trade Center at night, lit by the office lights in the windows. When I took it I thought, oh, yeah, this is a perfect symbol of consumerism, materialism, all of that. But after 9/11 it became a memorial image, like two candles set on the altar of life and death. Esquire Magazine gave me an assignment to photograph some aspect of America after 9/11. I just didn’t feel comfortable going someplace like the Grand Canyon, so I went to Katz’s Delicatessen. I spent a month at Katz’s making photographs of people eating pastrami, because I wrote, “Pastrami and Peace Go Together.” You feel very peaceful when you are digesting pastrami. I felt that freedom was about being able to photograph the impossible or the vulgar or whatever, or simply people enjoying themselves.

What projects are you involved with at present?

I still do some editorial photography. In fact, I just did a really interesting project with CareOregon, a private healthcare company that asked me to photograph a number of their members. These are people who are very, very sick. They are in their homes, not in the hospital. CareOregon made two beautiful exhibitions of the work, one at their headquarters in Portland and one in the Department of Human Services Building in Salem. Legislators got the chance to see people who really need care, and who are having good care right now through CareOregon. There were testimonials that were heart-wrenching.

You’ve mentioned in interviews being influenced by W. Eugene Smith and Robert Frank and have said, “Cartier-Bresson was Bach, Smith was Beethoven, and Frank was Claude Debussy. They’re all in my DNA.”

Well, definitely Smith was an influence because his photographic essays published in Life were very powerful. To some extent I was influenced by Robert Frank, but I moved away from him completely when I did East 100th Street.

Do you have any final statements to make about your work?

I would say I work out of a state of mind. When I’m photographing the dwarf in the circus, I’m confronting myself as a giant compared to this dwarf, but I’m not a giant compared to other people who might be a foot taller than I am.

So then I confront another reality; I’m in another state of mind. Even in the Civil Rights Movement I’m erasing my own heritage and the town I grew up in. We didn’t have any social experience with black people at all. So I’m learning about that oppression as I go deeper into the Civil Rights Movement. And East 100th Street is another frame of mind. Then I work on that. I don’t read an article in The New York Times and think, well, that’s a good idea, I’ll work on that. No, my work is very personal. It’s a personal barometer of my life, a voyage of consciousness that is my life’s work. Each one is different. My wife says, “You always start with zero, you erase your clichés,” as I did in Paris. You’re only seeing what I ended with, what I felt the thing is. So there’s a psychological, there’s a visual, there’s a contemporary, there’s an artistic element. I, personally, have been printing my body of work during January and February for the last two or three years, and I’ve accumulated about 1,200 prints in that time. I’m doing it because it needs to be done. One of my publishers, Gerhard Steidl, who does beautiful, highest-quality work, and who published England/Scotland 1960 in 2005 and Circus in 2007, is talking about publishing a four or five volume set of books of my life’s work. That would be great, if it happens. I would also like to give my wife Emily credit for her keen intelligence, visual acuity and inspiration through all these years that we have lived and worked and raised our children together.

Jain Kelly was the assistant director of The Witkin Gallery in New York City from 1971-78. She has written numerous articles on various aspects of photography and is a fine-art photography consultant to collectors. Her email is [email protected].

You may like

-

Cara Barer’s ‘Bibliomania’: A Captivating Exploration of the Transitory Nature of Books

-

Exploring Douglass’s Legacy: Isaac Julien’s “Lessons of the Hour” at MoMA

-

Exploring Maternal Bonds: The Intimate Photography of “Don’t Forget to Call Your Mother” at The Met

-

Between Dreams and Reality: The Surreal Artistry of Miss Aniela (Natalie Dybisz)

-

Focus Fine Art Photography Magazine Statement on the Passing of Elliott Erwitt

-

REVIEW: Play the Part: Marlene Dietrich