Behind the Lens

The Time of His Life: Lawrence Schiller

Published

1 year agoon

In the 1960s before 24-hour cable television, before cell phone cameras and the full tsunami of transient images of today’s world that now engulfs us, we turned to the famous photo magazines — LIFE, Look, Paris Match — for pictures of what was going on in the world. In that era the photojournalist held a special position. The “paparazzi” stigma had not yet stained the profession and to an extent many saw photojournalists as heroic. They bore witness — often artfully, usually courageously — to things we wanted to know about. Some photographers’ names still resonate from those years, but where names have faded from memory, the iconic images of photojournalists who always seemed to be where the signal events of that era were taking place continue to reflect the vibrant energy and high drama of those years.

Lawrence Schiller was one of those photographers whose name may have been forgotten, but whose photographs have not. Beginning last year a touring exhibition of his work has been drawing very large audiences in Beijing, Hong Kong, Salzburg, Berlin, London, and Sofia, Bulgaria. Indeed, in Bulgaria over 16,000 people lined up to see Marilyn Monroe and America in the 1960s, a paid-admission exhibition.

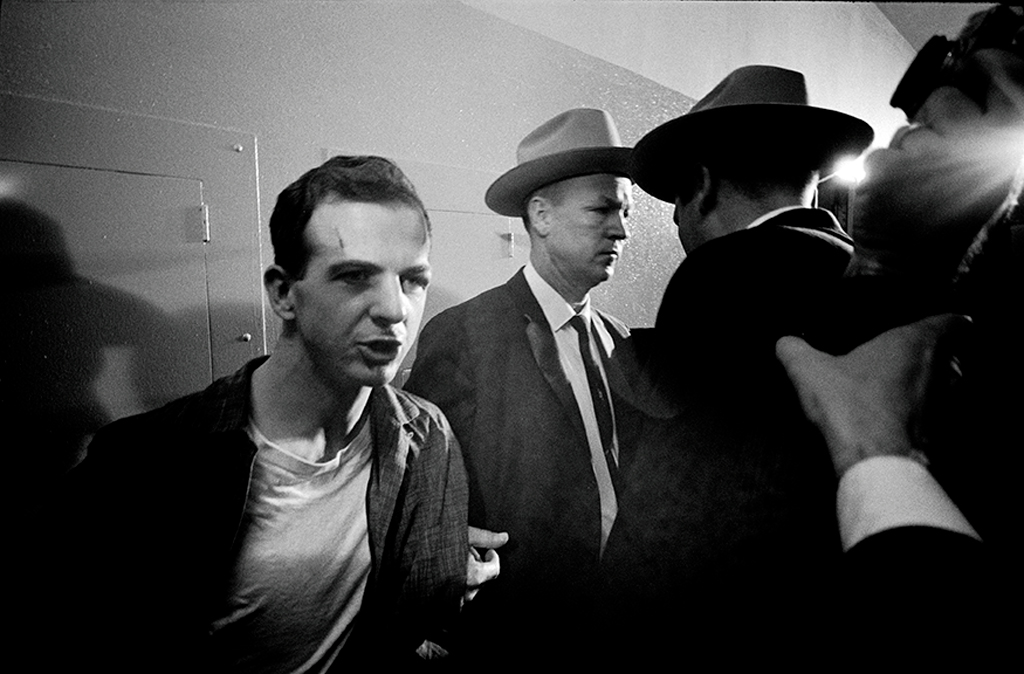

What could account for such an astounding turnout even for photographs of Marilyn? Schiller — as amazed as anyone else — wanted to know, and so he conducted a survey during the last 60 days of the show’s run to find out. “The response was very interesting,” says Schiller. “The demographics said they knew about the events in America in the ’60s, but had never seen images of them. They’d heard of [LSD guru] Timothy Leary, but [had] never seen a photo. [JFK assassin Lee Harvey] Oswald, but not a photo. The socialist government had controlled the media in those years. Same in China. They’d never seen that image of Oswald’s gun. They’d heard about the acid generation, but had never seen photos of [On The Road author] Jack Kerouac and people like that. So [the exhibition] wound up being bigger than we’d ever imagined.”

And the success Schiller’s images are enjoying with collectors matches the success the exhibition has enjoyed with the public. The relationship isn’t accidental. Schiller had commercial success in mind from the beginning. Schooled in business by his father from an early age (“I was behind the retail counter from the time I was maybe 9 or 10 years old”), Schiller could always see how to turn photographs into money, “and that may have worked against me being a photographer,” he says. Certainly, it set the stage for some criticism over the years from fellow photographers less commercially minded (and thus less commercially successful) than Schiller.

A little criticism hasn’t stopped or even slowed Schiller in a career that began in photojournalism but evolved into producing and directing motion pictures for television (five Emmy-winning) and writing and publishing many well-known best sellers (American Tragedy, on the O. J. Simpson trial, and Perfect Murder, Perfect Town, on the Jon-Benet Ramsey case). Along this colorful path, Schiller’s knack for making connections and making deals also ended up rescuing W. Eugene Smith, one of the least commercially minded photographers of that era, from a hospital in Japan and making the deal that finally brought Smith’s classic Minamata (1973) into print.

Schiller led such a varied, interesting, and successful life as a photojournalist, it’s hard to know where to start in filling in the background. Jacob Deschin called him “a pro at sixteen” in US Camera back in 1953 when Schiller was still in high school. He was winning awards right and left. He wrote a chapter on lighting for the Graphic-Graflex Photography book, had photos published in The Saturday Evening Post and LIFE, and shot his first playmate for Playboy in 1958. (He would, incidentally, go on to photograph Paula Kelly for Playboy in 1969, the first playmate to have her pubic hair escape the previously ubiquitous editorial airbrush.) Schiller’s photo of Nixon losing to John F. Kennedy won the National Press Photographers Association “Best Storytelling Photo” award in 1961. Two years later, it would be his photo of a Dallas policeman holding Lee Harvey Oswald’s rifle above his head in a media-crowded hallway that would forever nail that moment from that awful time in the minds and memories of millions.

It was two hours spent shooting on a Hollywood sound stage in 1962, however, that has pulled Schiller’s photographic career back into view. On that day he was one of three still photographers on the set of Marilyn Monroe’s last movie, Something’s Got to Give, the day she famously shed a flesh-colored bathing suit and swam naked for the cameras. The iconic photos of Marilyn peeking over the edge of the pool and toweling off beside it are Schiller’s.

One of the three photographers there that day worked for the studio; to the other, William Reed Woodfield, Schiller said: “Bill, two sets of photos will just drive down the price. One set, and we control the market for these pictures.” They combined their efforts and captured worldwide sales. Marilyn, too, had a good head for business, says Schiller. She later approved his images from this shoot, cutting up negatives she didn’t like with scissors.

The day before her death, Schiller dropped by Monroe’s home to discuss a planned photo shoot for Playboy. “She was out in the garden pulling weeds,” Schiller recalls. The next morning a phone call told him she was dead. Schiller’s image of DiMaggio at Marilyn’s funeral might have been the end of Schiller’s Marilyn story, but there were to be two other chapters, including the current interest in all of his photographic work from forty years ago. The first of these additional chapters came along ten years later: Schiller, a natural-born storyteller recalls it this way: “The way the whole thing started was with a gallery called David Stuart on La Brea in LA, and David [who usually specialized in ceramics] called John Bryson who had photographed Marilyn a lot and said the pottery business is a little slow: I want to get some foot traffic; would you like to have a show of your Marilyn photos in my gallery? Bryson said to him, ‘Well, if you really want to have an exhibition, you should do it with all LA photographers. You should call Larry Schiller and maybe Doug Kirkland.’

“So we all had a lunch together, and I said at the lunch ‘This is stupid: if you want to do it right, then we should get 24 photographers because the minute we do it somebody else is going to do it in New York. So what about Bert Stern, what about Avedon, what about Andrea de Dienes?’ So Dave Stuart said, ‘Do you think you can get everybody together?’ And I said, ‘Yeah.’ So we made a deal where my company would own a third, the photographers would own a third, and we would eventually find a writer, and from the very beginning we conceived it as an exhibit from which a book would come out of it.

“Well when we opened the exhibit at the David Stuart Gallery people were lined up 10 blocks long. That’s thousands of people headed to a little gallery, 20 by 28 feet.”

But the deal wasn’t fully done, though Schiller was already designing the book. With the press clippings and the book dummy in hand, he flew to New York to find a publisher. He went first to Random House. Schiller continues: “…[A]nd they wanted a certain writer to write it, and I didn’t like that writer. I said, ‘That writer’s never written an original word.’ I said, ‘This book needs controversy.’ They said, ‘What do you mean?’ I said, ‘This book is going to have the cover of Time and the cover of LIFE magazine the same week!’ And they said, ‘Come on Larry let’s talk about something else.’ So I walked out: they gave up the book.

“And then Harold Roth at Grosset & Dunlap called me at my hotel and said, ‘I hear your Marilyn book is available.’ I said. ‘Yes, it is.’ And he says, ‘Well, we publish Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys, and I said, ‘Well I don’t know if you are going to want to publish Marilyn Monroe with no clothes on.’ And he says, ‘Well, we’re trying to change the image of this company.’ So we meet in his office, and he says, ‘How much do you want for the book?’ And I say, ‘I want $150,000 (remember this was 1971). I want $50,000 to split up with the photographers, $50,000 for myself, and $50,000 for a writer.’ And he says, ‘Who do you want to write the book?’ and I said, ‘Get me Gloria Steinem or get me Norman Mailer.’ They made a call and got me Mailer.”

Following the success of the book and the exhibition, Mailer and Schiller went on to collaborate on The Executioner’s Song (the Pulitzer Prize-winning book about murderer Gary Gilmore and the movie version which won two Emmy Awards), Oswald’s Tale (about Lee Harvey Oswald), and The Faith of Graffiti (photographs of New York graffiti art by Jon Naar and Mervyn Kurlansky). In a sense, the collaborations continue: In 2008 Schiller became Senior Advisor to the Norman Mailer Estate and currently serves on the board of the Norman Mailer Writers Colony.

The last and current chapter in the story of Schiller’s Marilyn photos came about ironically because of Schiller’s current project having to do with contemporary art in China. Schiller seems always to have had a project. By the time of the Marilyn book in 1972, he had already begun to move into producing and directing movies and turning interviews with high-profile crime figures into best-selling books. The assassinations of John and Robert Kennedy, he recounts, fixed his long-standing interest in antisocial behavior. After watching people drop acid at Canter’s Delicatessen in Los Angeles, he basically shamed LIFE into running a major photo essay on LSD when no one really wanted to touch the story. Not surprisingly, Schiller went on to publish those photographs as a book.

Through the movies, Schiller has made a lot of money over the years, and the movies themselves taught him how to do it at an early age. Schiller recalls: “When I was about 16 years old, I was watching a show in the mid ’50s where they talked about Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz and how all their shows were owned by RKO pictures. But they had kept the ownership to the kinescopes, and the kinescopes were like a negative the show said. So every time the studio wanted to make more prints of the shows, they had to come back to Lucy and Desi, and they charged money to print from the kinescopes, and that’s how they became wealthy. And that stuck in my mind: the word kinescope and the word negative.

From that day on I would take less money for my photos, and I would retain the rights.” Schiller’s love for still photography never really went away. Indeed, still work led him into movies. As special still photographer on Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), he ended up editing the still collage in the movie. He’d go on to create others for Lady Sings the Blues (1971). Along the way, he produced and directed Double Exposure: The Story of Margaret Bourke-White, based on Vicki Goldberg’s much praised biography.

Schiller had wanted Glenn Close for the movie, but Ted Turner thought Farrah Fawcett would bring higher ratings, so he recalls the project with mixed emotions. Schiller looks on the current resurgence of interest in his photojournalism with a kind of joyful amazement. For him it’s a happy by-product of being a good host. But let Schiller tell the story: “It came about by pure coincidence. What happened was that in 2004 the Chinese government through CCTV asked to license some 30 films I’d had made for Court TV on Dr. Henry Lee, the criminologist from the OJ days. Part of the deal was a trip to China. There I discovered avant-garde Chinese art. I was probably one of the last to ‘discover’ it, but there you go.

“Through that discovery, I met a lot of important art collectors, and one of them was having dinner in my home. Between dinner and dessert, I showed him through a building behind my home that holds my files, my offices and so on. In the office there were a bunch of boxes with all my photos from the 1960s being prepared to go to the Harry Ransom Center in Texas; that’s where my archive is going.

“So this collector begins asking, ‘Who took that picture? I know that picture.’ I say, ‘I did when I was 26’ and so on. We got to the third picture and he says ‘Could I have that one? Would you sign it for me?’ I say ‘Well, you know I don’t really sign pictures; all this stuff went into boxes in the ’70s, and we’re just trying to figure out what’s in here.’ So I signed the photo and gave it to him, and we went back into the house and had dessert.

“He says ‘You know photographers all over the world are doing signed, limited editions. If you shot these pictures of Marilyn Monroe, why aren’t you doing that?’ I said, ‘I don’t have time to do that; I got Bert Stern started doing that. When I did the Marilyn book with Mailer that was the beginning of it all.’ So he says, ‘Why don’t you do it?’ I tell him again, ‘I don’t have the time to do it.’ He says, ‘I’ll put up the money; we’ll find somebody to do it. What would it cost?’ So the short and long of it is we finally figured it would cost around $800,000. And he says, ‘I want 25% ownership. I’ll have the money in your bank tomorrow.’ And he did.”

Unlike Bert Stern, who Schiller thinks made a mistake in releasing so many of his images of Marilyn, Schiller has authorized only a handful. Printed in silver gelatin and platinum, the editions are doing very well. Are the photos art? Schiller makes no such claim. “It’s the museums and the collectors who see the pictures as art,” says Schiller. “I don’t see myself as an artist. Eugene Smith was a great artist and Danny Lyon’s work had an art feel to it, and Ernst Haas and Margaret-Bourke White — her black-and-white images all had an art feel to them — but mine I always felt were more like a sponge, if you know what I’m saying. I was preserving what was in front of me.

“There’s a difference,” says Schiller, “between art and imagery that sells (and often for a lot of money), but still may not be art. I really don’t know where my images kind of fit. They’re selling but are they selling because they’re art or because they’re history? There are a few images of mine, like Buster Keaton, which people consider art, or James Earl Jones and images like that, but I think the greater number of my pictures are selling because they are the iconic images of history.”

As the resurgence of interest in Schiller’s images affirms, photos from the past accrue different values as time moves on. Whether as art or history, we’re glad to have the pictures.

James Rhem is the author of Ralph Eugene Meatyard: The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater & Other Figurative Photographs (ISBN 978-1891024290) and the Phaidon 55 Series on Aaron Siskind (ISBN 978-0714841519). He is also the Executive Editor of the National Teaching and Learning Forum out of Madison, WI. For more information regarding his books or his work, please contact James at [email protected].

You may like

-

Focus Fine Art and Art Vibe Join Forces for Exclusive Joint Venture at Red Dot Miami 2024

-

Timeless Impact: New York’s Profound Photography Exhibition

-

Flóra Borsi: Shaping Reality Through the Lens of Surrealism

-

Cara Barer’s ‘Bibliomania’: A Captivating Exploration of the Transitory Nature of Books

-

Exploring Douglass’s Legacy: Isaac Julien’s “Lessons of the Hour” at MoMA

-

Exploring Maternal Bonds: The Intimate Photography of “Don’t Forget to Call Your Mother” at The Met