Collectors Corner

Through the Lens of a Legend: A Retrospective on Edward Weston’s Photographic Journey

Published

1 year agoon

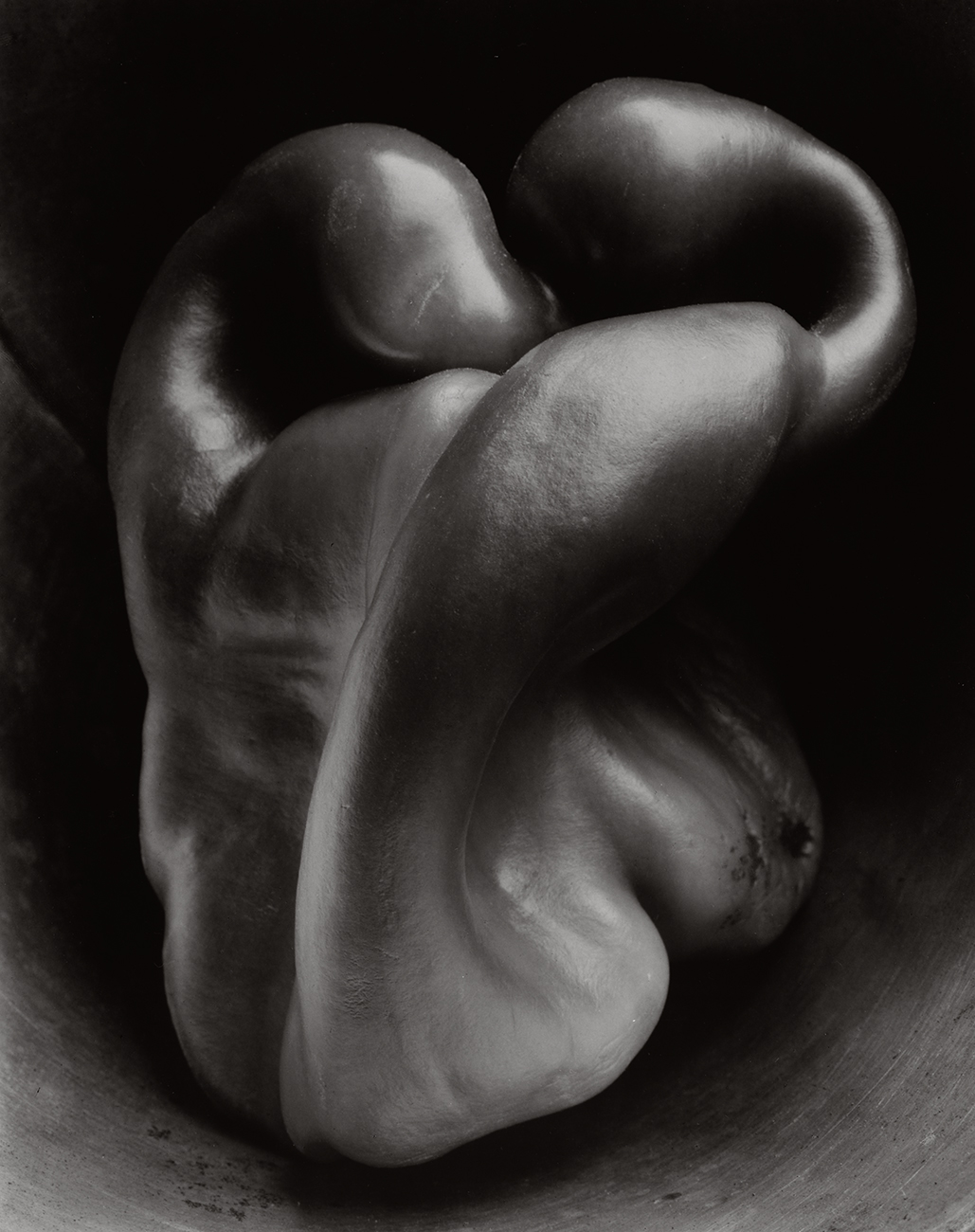

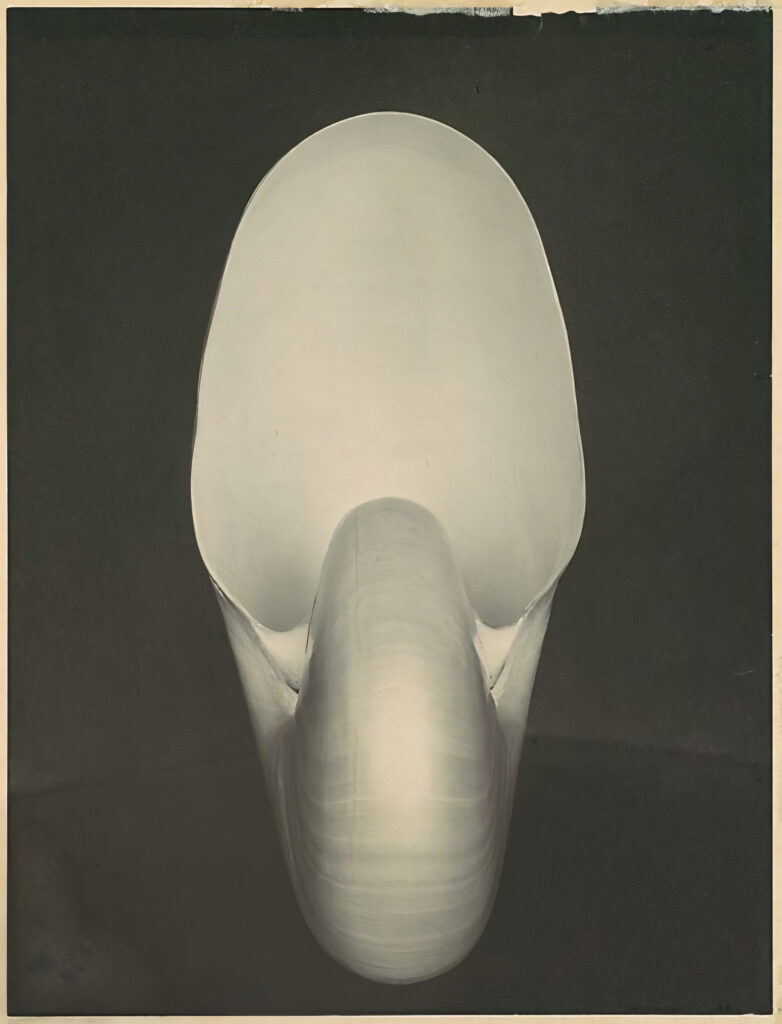

The dunes, shells and peppers, of Edward Weston are classics of American art created by a 20th-century master. Weston’s vision is held by culture, not just by photography. His vision defines a value, a set of assumptions about formal balances and natural harmonics and the possibility of their isolation and transmission through the special gift of his aesthetic genius. Weston’s often self-proclaimed perfect light and aperture gave promise to a notion of unity where dunes shared a sensuous line that traced volumes more usually described through poetry and music. Weston, with friend and colleague Ansel Adams, have been poster makers, arbiters of a populist co-modification that well after their deaths has floated the boat of art in the medium of photography. This is an irony that wasn’t lost on Weston, who never enjoyed significant profits from his images. But neither was the legacy of his art lost. He prepared the way toward his memorials with the most articulate of self-definitions—an investment of self-appointed critical theory as fine as any written—his two volumes of reflection, The Daybooks, first published by George Eastman House in 1961 and 1966. George Eastman House holds the original edited typescript manuscript of the journals together with a rich collection of other ephemera. The Center for Creative Photography in Tucson also holds valuable archives along with the Dayton Art Institute, which holds an archive of photographs and manuscripts from Weston’s sister Mary Weston Seaman.

It was in the year 1923 when Weston came into what would be his own. He had been to New York in 1922 to visit the aging guru, Alfred Stieglitz, and received approval for his new work, which was a tough-minded, tectonically articulate appreciation of the Armco Steel Mills in Middletown, Ohio. So it was in 1923 when Weston left his wife and children to travel with his lover, Tina Modotti, to Mexico, where they remained for the next three years. He also was leaving behind his old way of working, abandoning the soft focus, restrained gray scale of pictorial imagery for a more declarative modernism. This also was a vital period in Mexico, a revolutionary time for the arts and culture, with great humanist expression from Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Frida Kahlo, and Miguel and Rose Covarrubius. In 1926, Weston finally returned to family and home in California; it was his 40th year. In 1928, he opened a San Francisco studio with his son Brett, and then moved to Carmel, where he remained until his death in 1958.

Weston was born in 1886 in Highland Park, Illinois, near Chicago, where he grew up. He began to photograph at the age of 16 after receiving a Kodak Bull’s Eye #2 camera as a birthday present from his father. His first photographs captured the parks of Chicago, where he lived at the time. An indication of how seriously he took this beginning is his commemoration of his 50th anniversary in photography in 1952 with a special portfolio.

In 1906, Weston photographed professionally in Chicago and California; he attended the Illinois College of Photography in 1908. He worked in California as a door-to-door portrait photographer or as a studio printer. He married Flora Chandler in 1909, a wealthy woman seven years his senior; her father was successful in real estate and later became publisher of the Los Angeles Times. Edward and Flora quickly had four sons, Chandler (1910), Brett (1911), Neal (1914) and Cole (1919). Between 1911 and 1922, he operated his own portrait studio and made pictorial salon images, successfully entering international competitions and exhibitions. With many, Weston perceived the shifting tenor of culture at the end of World War I. The case for fine art photography had been won; it was a time to see more clearly and understand more directly. Photography, rather than trying to be richly connotative, should depict “the very substance and quintessence of the thing itself,” Weston declared. Through the 1930s, Weston enjoyed publication and significant exhibition, work with the WPA Federal Arts Project in New Mexico and California; and in 1937, the first Guggenheim Award made for photography. In 1938, Weston married Charis Wilson, with whom he had lived and photographed since 1934. She is the model for much of his work during this period, and together they published two books, The Cats of Wildcat Hill and California and the West. They were divorced in 1946. Weston was a founding member of Group f.64, which included California-based artists Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham and Willard Van Dyke. Suffering from Parkinson’s disease, Weston ceased exposing photographs in 1948. His sons Brett, then Cole, took over printing his work for him. In 1955, Brett took on a project to make eight prints each of 1,000 negatives Edward selected. These were called the “project prints,” and about 800 negatives were realized. He died on January 1, 1958, in Carmel.

George Eastman House holds more than 250 prints by Edward Weston, including a collection of personal images he made with Tina Modotti in Mexico. Gustavo Lozano, an Andrew Mellon Fellow in the advanced residency program at George Eastman House, has been studying the Museum’s Weston holdings. He reports that during his formative years in the 1910s and early ’20s, Weston’s photographic technique was influenced by the dominant Pictorialist aesthetic of the moment. His photographs from that period were printed by contact on matte platinum, palladium or gelatin silver paper. Later starting around 1922, Weston progressively abandoned his romantic, diffused aesthetic and shifted towards a more objective form. He began using sharper lenses, a large format camera with sharp focus in every plane and printed (still by contact) on smooth, glossy gelatin silver paper without retouching. Lozano, formerly the photography conservator at the National Library of Anthropology and History in Mexico, observed that Weston’s lenses were a very expensive anastigmat and several soft focus, among them a Wollensak Verito and a Graf Variable. George Eastman House has in its collection a Rapid Universal Lens (Bausch & Lomb Optical Company, Rochester, New York) inscribed, “To Brett – Dad ’37.” Weston made use of a 3¼ x 4¼ Graflex camera, a 4 x 5 RB Auto-Graflex and an 8 x 10 Eastman View No. 2D.

The inscriptions in Weston’s prints changed over time, Lozano notes. In his prints from his early works until the ’20s, Weston signed in full, dated and inscribed his prints with pencil below the photograph and sometimes along the bottom edge on the mount. In his late works and particularly in his last two big projects, the “50th Anniversary Catalog” and the “Prints Project,” the full signature in script is transformed into the printed initials “EW” and the date, and the title was no longer included. The Weston legacy has been that of carefully rendered, finely printed work without complex manipulation. Weston’s style was to use simple materials very well. It is an axiom that has sustained his regard into our time.

Anthony Bannon is the seventh director of George Eastman House, the International Museum of Photography and Film in Rochester, New York.

You may like

-

Cara Barer’s ‘Bibliomania’: A Captivating Exploration of the Transitory Nature of Books

-

Exploring Douglass’s Legacy: Isaac Julien’s “Lessons of the Hour” at MoMA

-

Between Dreams and Reality: The Surreal Artistry of Miss Aniela (Natalie Dybisz)

-

REVIEW: Play the Part: Marlene Dietrich

-

Through the Lens of Tragedy: The Final Frames of Gilad Kfir, Photographer and Aspiring Father

-

TOMAAS: Bridging Realms of Surrealism and Post-Humanism