Vintage Focus

De Clercq

Published

1 year agoon

By Alex Novak

Louis-Constantine-Henri-Francois Xavier De Clercq was born on Christmas Day in 1836 in Oignies, France. Doubly blessed with the support of a wealthy French family, De Clercq early on fell in love with archeology and ancient cultures.

But the beginnings were not auspicious for the young De Clercq. Even at 23, he had not yet been meaningfully employed. Through family influence he became a courier for Napoleon III during the Italian campaigns in early 1859.In their efforts to give the young man a more classical experience other friends of his family would influence him in what was to become his most important life work. The marquis Melchior de Vogue, noted archeologist and a friend of De Clercq’s brother-in-law, and Emmanuel-Guillaume Rey, an historian of Crusader Castles, were to play major roles in this life change. Melchior de Vogue suggested that Rey hire the young De Clercq as Rey’s assistant on an expedition to Syria and Asia Minor that was being commissioned by the French Ministry of Public Instruction. After interrupting a trip to Switzerland, De Clercq joined the expedition in August and remained with Rey until December 5, 1859. Part of the reason for Rey’s hiring of De Clercq apparently stemmed from the young man’s ability with a camera. According to Rey’s notes, “his experience and success as a photographer promised that I would have in him a useful assistant.”

Oddly enough, little is actually known about De Clercq’s early photographic training and experience. Through the recent discovery of De Clercq’s waxed paper negatives, we may now surmise that French photographer Gustave Le Gray’s teachings may have been influential on De Clercq, either before or during his journeys. There have also been other clues noted by other authors, including De Clercq’s own note about pursuing his work “with perseverance,” which was a phrase that Le Gray was very fond of repeating and which provided ironic fodder for his critics. As photo historian Eugenia Parry Janis noted in the very excellent Louis De Clercq: Voyage en Orient, “The fact that his work is brilliantly executed with a consistent vision of his subjects throughout the entire corpus of the pictures, makes it difficult not to see the force of Le Gray’s influence.” De Clercq’s use of waxed paper negatives was probably due to the influence or even direct suggestion of Le Gray, who had perfected and registered several waxed paper processes in France before he left for Syria and Egypt in the 1860s himself.

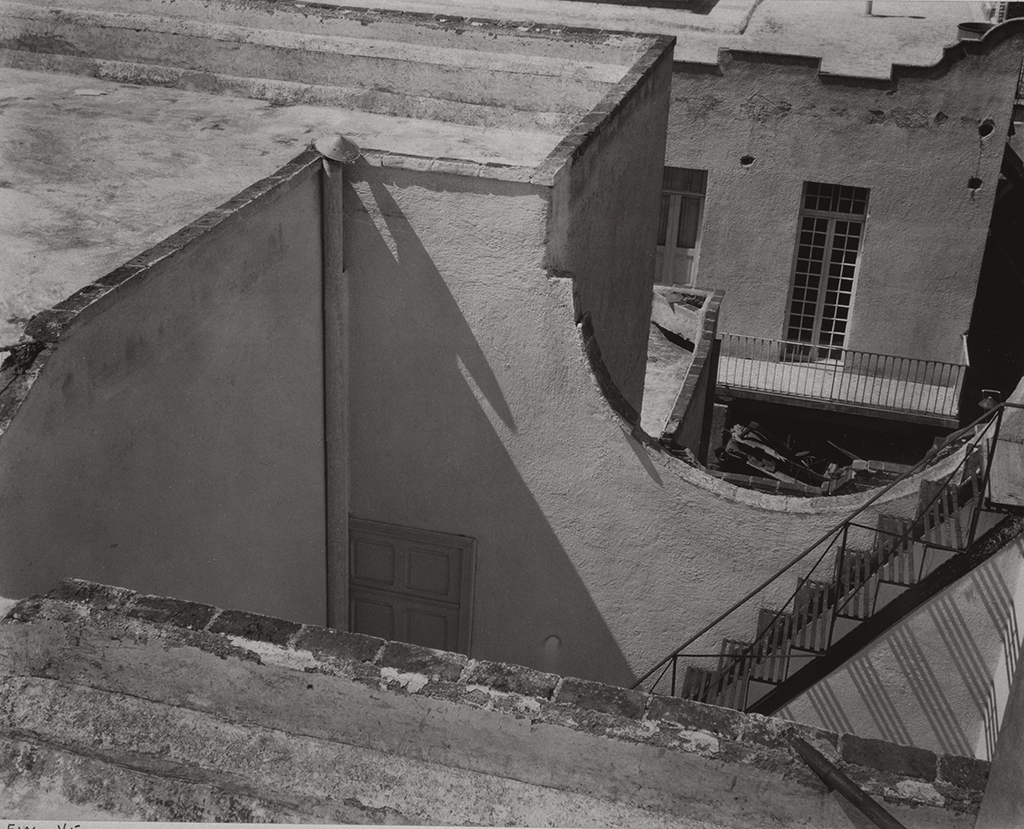

De Clercq’s images are stunning and give a greater sense of the overwhelming size of many of these archeological wonders and monuments than nearly any other of his contemporaries, despite the fact that he would rarely use people for purposes of scale in his images, as many of these other early photographers would do. As Janis noted in her introduction, De Clercq’s work also often gave one a sense of “precariousness amid monuments constructed to endure for millennia. There is something irregular, unusual, even absurd here, as if one were viewing a disoriented dinosaur. In the Hemicycle the broken entablature leans against the stone socles as if about to push them off their vertical axes.” Janis also cited his image Heliopolis (Baalbeck), Interior of the Temple of Jupiter, Syria, where she notes “De Clercq fixed upon the colossal keystone that has slipped out of place, and that suspended thusly, seems about to drop like the blade of a guillotine.” In 1861, De Clercq wound up publishing some 222 photographs in six volumes: I. Picturesque views of the cities and monuments of Syria; II. Castles in Syria at the time of the Crusades; III. Views of Jerusalem and of the Holy Places in Palestine; IV. The Stations of the Cross in Jerusalem; V. Monuments and picturesque sites in Egypt; VI. Voyage in Spain, views and picturesque monuments. He exhibited photographs from these sets almost immediately at the Fourth Exhibition of the SFP (Societé Française de Photographie) in Paris, even though he was apparently not a member at the time.

Although he self-published these volumes in a reported edition of 50, only about a dozen copies — both intact and broken — are known to have survived. Most of these copies are in public institutions — unlike his negatives. In January 2003, most of his paper negatives were auctioned off in Chartres, France. Oddly enough these had disappeared for over 140 years before coming to light. A French antique dealer had found them in a file folder that dated to about the 1920s. Many from the Egyptian series were missing from the group and remain unaccounted for. Perhaps further scientific study of these negatives can provide a more direct link to Le Gray’s own waxed paper processes.

De Clercq died in his hometown of Oignies on December 27, 1901, just two days after his 65th birthday. Prices on De Clercq’s prints in good condition usually range from about $2,500–$50,000. His paper negatives, which are, of course, unique, are difficult to find. Many have now disappeared into large private collections. They also have usually ranged, when available, from about $2,500–$50,000. Overall condition, tonality and specific image determine prices. The Tower of Gold from the Spanish album is perhaps the most expensive De Clercq positive print and will often sell at the top end of the range. A broken set of Louis De Clercq albums, minus the important Syrian forts album, sold to a phone bidder for over $410,000 in mid-2006 in a small French auction in suburban Paris. The condition was generally considered by most observers to be just “average” on this group, despite the high price tag.

The best single reference book on Louis De Clercq — in fact the only one focused on him to date — is Rolf Mayer’s Louis De Clercq: Voyage en Orient, which was published by Edition Cantz in 1989 in conjunction with an exhibit at the Mayer and Mayer gallery in Cologne at the end of that year. The text is in English, German and French. The Gilman Company’s fine set of De Clercq’s work, which is now a part of the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection, was used for 222 of the reproductions. The Musée d’Orsay lent a 223rd image that was a part of an album in its collection. Besides Rolf Mayer’s work in compiling the images and information, Eugenia Parry Janis wrote the excellent introductory essay and notes. Unfortunately this book/catalogue is now quite scarce and usually sells for $500 to $600 or more when in its fragile slipcover. The book is not a complete compendium of De Clercq’s images, however, because a number of paper negatives surfaced in the Chartres auction that were not included in the albums.

Alex Novak is a private dealer that has over 30 years experience in the photography-collecting arena. His companies, Vintage Works and Contemporary Works, are a member of the Association of International Photography Art Dealers (AIPAD). These companies sell important 19th, 20th and 21st-century photography in every medium. There are over 3,500 images in inventory, which can be viewed on the following websites: www.iphotocentral.com, www.vintageworks.net, and www.contemporary.net. He can be contacted at 1-215-822-5662 or [email protected]

You may like

-

The Intersection of Technology and Fine Art:

-

-

Painted Smiles and Hidden Tears: A Photographer’s Journey into the World of Circus Clowns

-

THE PHOTOGRAPHY SHOW PRESENTED BY AIPAD: EXHIBITION HIGHLIGHTS

-

Preserving the Past, Capturing the Present: The Journey of Three Traveling Tintype Photographers

-

Fine Art Photography and the Human Condition: A Study of the Emotional and Psychological Themes in Contemporary Photography

By Anthony Bannon

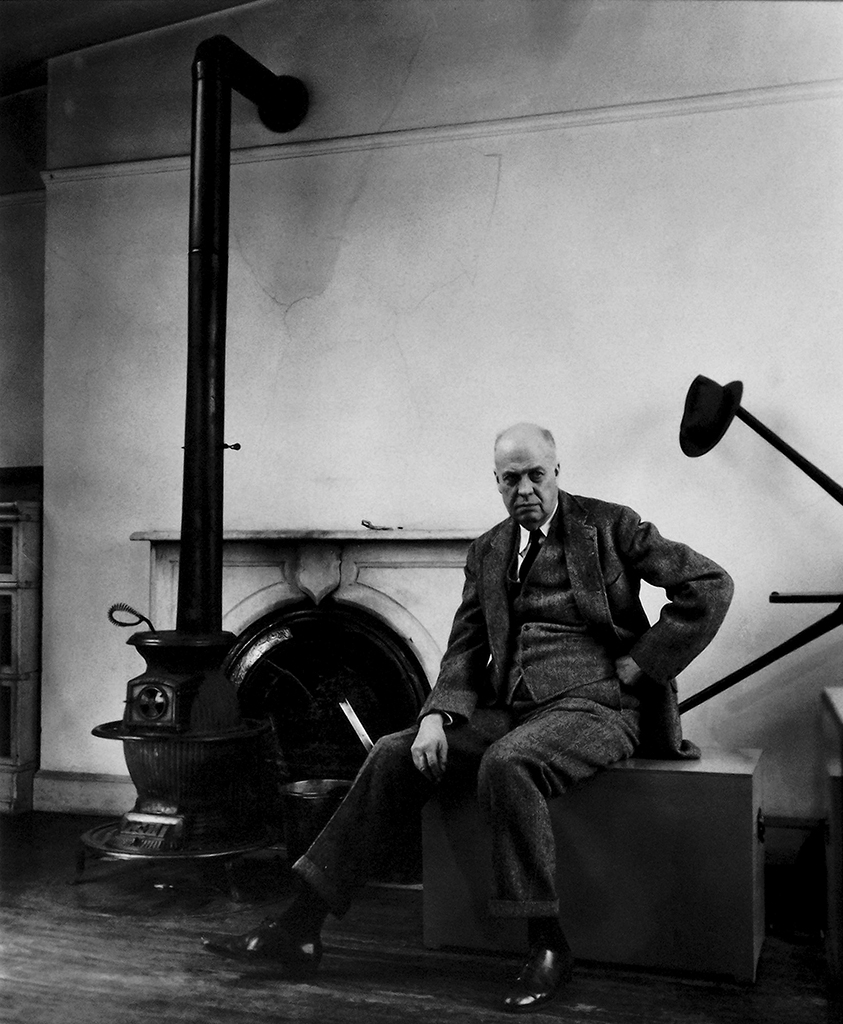

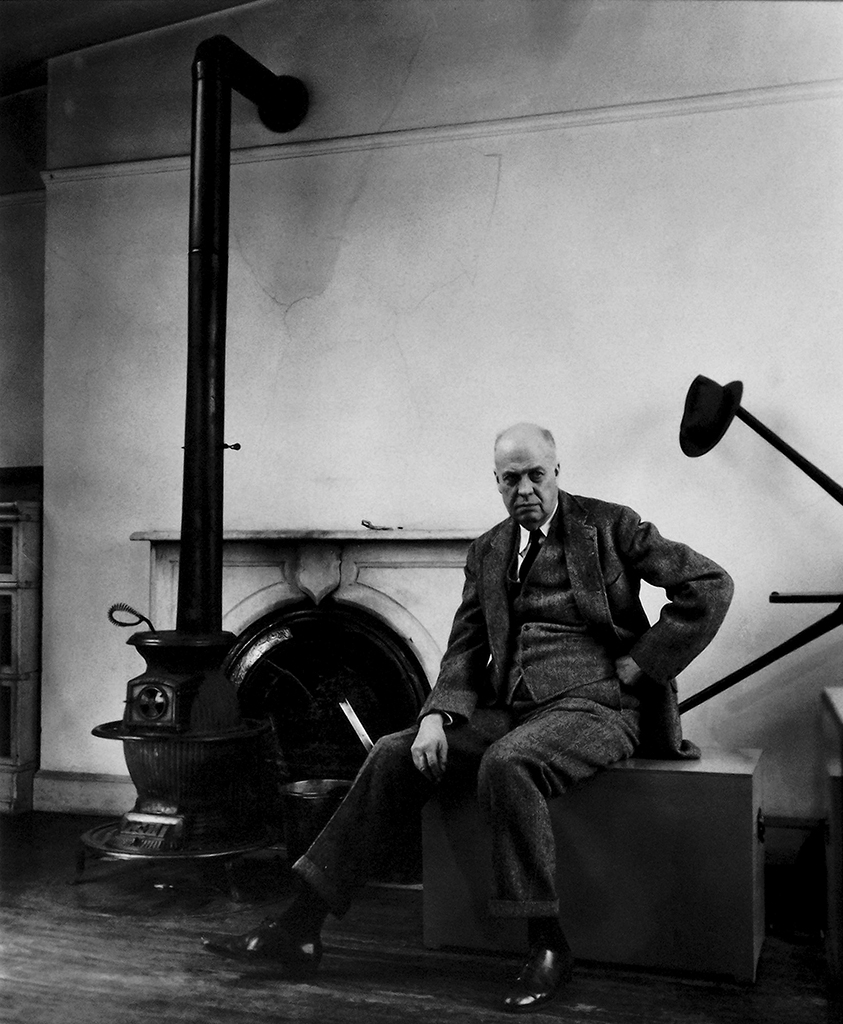

Berenice Abbott’s New York may be a thing of the past, but the spirit of her depiction—the tender gaze at what was before her during the 1930s—endures as a treasured statement of the rich spirit of the place. During the late ’20s, Abbott engaged looking at people, mostly artists in Paris, and for the clarity of her vision, these images have become icons—surrogates of such as James Joyce, Andre Gide, Jean Cocteau and Eugène Atget.

Abbott was born in 1898 in Springfield, Ohio, and studied art and sculpture in New York City, Berlin and Paris. In 1923, while living in Paris, she began work as a studio assistant to American artist Man Ray, and he introduced her to the work of Eugène Atget, whose chronicles of Paris inspired Abbott’s efforts in New York after her return to America in 1929. The impact of Atget’s work upon her was “immediate and tremendous,” she declared. It was “the shock of realism unadorned.” When Atget died in 1927, Abbott kept his work alive by purchasing from the artist’s estate (with assistance from art dealer Julien Levy) the thousands of negatives and prints Atget had left behind. It was Abbott who saw that the work was chronicled, published, exhibited and finally acquired, principally by the Museum of Modern Art in 1968.

When Abbott returned to New York, she was captivated by the complex dynamics of the city—always in flux, a changing human and environmental scene of new construction and a burgeoning population: “the noble and the shameful,” she wrote, “high life and low life, tragedy, comedy, squalor, wealth, the mighty towers of skyscrapers, the ignoble facades of the slums, people at work, people at home, people at play.” So she took her large format camera, and made contact prints from the 8 x 10″ negatives it produced for the highest register of detail and pictorial information—realism unadorned.

From 1935 to 1939, she formalized the project as a part of the Works Progress Administration’s Arts Project, a federal effort to provide public service benefit and employment during the depression. The project concluded in 1939 with the publication of a book entitled Changing New York, highly collectible today. The negatives and a core collection of master prints are held by the Museum of the City of New York.

The ’30s were a time for the documentary photograph, a new realism in America, encouraged by the efforts of Roy Stryker and the Farm Security Administration, which also engaged a photography project to educate the nation about the struggle of rural America. Among the FSA photographers were Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, Arthur Rothstein, Ben Shahn and Russell Lee. The negatives from the FSA project are on deposit at the Library of Congress. During the ’30s and into the ’40s, Abbott worked with Margaret Bourke-White at a new magazine devoted to current affairs called Life. And she supported the efforts of two of the great documentarians, Louis Hine, whose career was coming toward its end and Lisette Model, whose career was only just beginning.

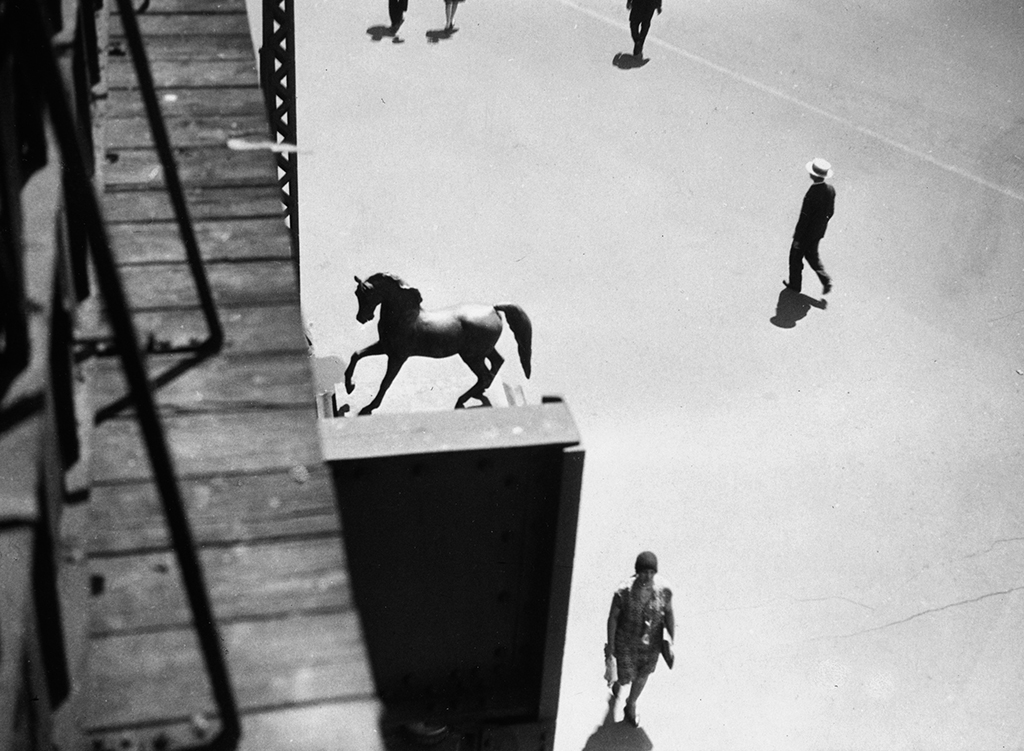

Like Atget’s documentation of Paris, when working on her own in New York, Abbott’s images depict people and places that no longer exist as they did then. They are valuable records, not simply objects of sentiment and nostalgia. Like Atget’s work before her, these are clear-headed statements of the way it was, participating fully within the time of their creation. The late Robert Sobieszek, curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and before that chief curator at George Eastman House, wrote that Abbott carried the modernist impulse “to render a moment of pure chance and implied integration.” He was speaking about her photograph from 1930, Horse Fountain, Lincoln Square, exposed from a vantage on the elevated subway line that no longer travels above ground on the upper West Side of New York. Sobieszek praised her sense of “serious play and new vision,” and echoed the sensibility of another fine critic. Calling her a “superior artist, one of the finest of her generation,” The New York Times art critic Hilton Kramer had written about a 1976 exhibition of Abbott’s work: “What is remarkable about these pictures of New York in the ’30s, which range from the most monumental subjects to the most workaday, is the degree to which they retain even now this sense of discovery—of something freshly seen and intensely valued.”

While Abbott continued her documentary work (most notably with a series of images made along U.S. Route 1, from Maine to Florida), she also immersed herself in the closely related discipline of science, as she pressed forward her commitment to discovery. Her great commitment and wonder with the observed environment was first displayed internationally in 1929 at the famous exhibition in Stuttgart, Film und Photo, where her work, together with work by Edward Weston, Charles Sheeler, Edward Steichen, Paul Outerbridge and Paul Strand, were declared the Neue Sachlichkeit, by art critic Carl Georg Heise.

From the mid-’40s and into the ’60s, Abbott illustrated the laws of physics in secondary school textbooks and worked under commission to create an exhibition on the “image of physics” for the Physical Science Study Committee. With her illustration of scientific text, Abbott lines up with her previous work, all of it free of sentiment, decidedly honest and direct. “The challenge for me has first been to see things as they are, whether a portrait, a city street, or a bouncing ball. The second challenge has been to impose order onto the things seen and to supply the visual context and the intellectual framework—that to me is the art of photography,” she wrote in a forward to Ten Photographs, a portfolio selection of her work created in 1976 in an edition of 50, with an introduction by Hilton Kramer.

Her medium was gelatin silver, mostly contact prints from 8 x 10″ negatives. In the =60s, with a series of images taken around her new home in Maine, she began to enlarge them to 11 x 14″ and 16 x 20″. Her signature, Berenice Abbott—sometimes in block letters, sometimes in cursive—appears in the lower right when the print is mounted; if unmounted, she signs or stamps on the back of the print, often with her Commerce Street address in New York, where she lived until the mid-’60s. A stamp from the Federal Arts Project of the WPA also identifies some vintage prints from Changing New York.

In 2002 Sotheby’s auctioned Abbott duplicates from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York, which, with the New York Public Library and Syracuse University, hold the major Abbott collections. The Sotheby’s catalog is a good resource on the artist, who, according to research done by Andrew Eskind at George Eastman House, is among the top 10 most collected photographers, with work held by more than 100 museums.

Another interesting resource is a lengthy interview with Abbott conducted by James McQuaid as a part of a George Eastman House oral history collection with many of the major photographers living in the United States in 1975. The House recently restored the original tapes. Abbott placed the most vigorous restrictions upon the transcript, saying that it “may be read only by serious research scholars using the facilities of the museum.” Thus the transcript has not been reproduced in its entirety.

Anthony Bannon is the seventh director of George Eastman House, the International Museum of Photography and Film in Rochester, New York.

By Anthony Bannon

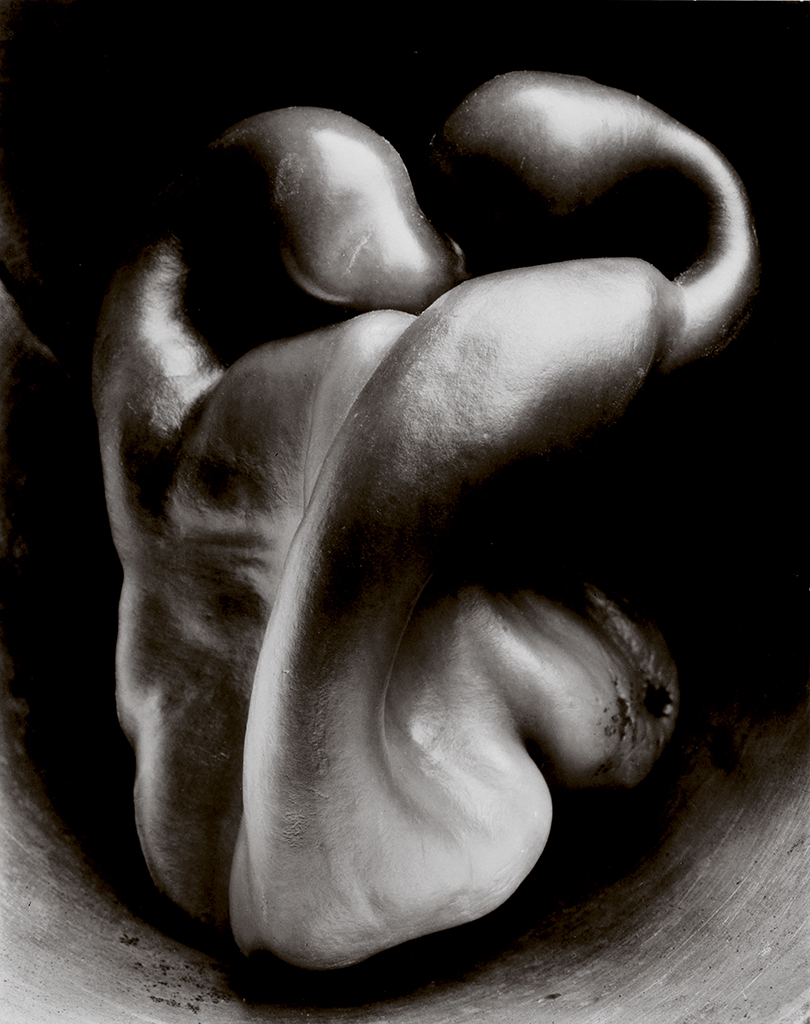

The nudes and dunes, shells and peppers, of Edward Weston are classics of American art created by a 20th-century master. Weston’s vision is held by culture, not just by photography. His vision defines a value, a set of assumptions about formal balances and natural harmonics and the possibility of their isolation and transmission through the special gift of his aesthetic genius. Weston’s often self-proclaimed perfect light and aperture gave promise to a notion of unity where nudes and dunes shared a sensuous line that traced volumes more usually described through poetry and music.

Weston, with friend and colleague Ansel Adams, have been poster makers, arbiters of a populist co-modification that well after their deaths has floated the boat of art in the medium of photography. This is an irony that wasn’t lost on Weston, who never enjoyed significant profits from his images. But neither was the legacy of his art lost. He prepared the way toward his memorials with the most articulate of self-definitions—an investment of self-appointed critical theory as fine as any written—his two volumes of reflection, The Daybooks, first published by George Eastman House in 1961 and 1966. George Eastman House holds the original edited typescript manuscript of the journals together with a rich collection of other ephemera. The Center for Creative Photography in Tucson also holds valuable archives along with the Dayton Art Institute, which holds an archive of photographs and manuscripts from Weston’s sister Mary Weston Seaman.

It was in the year 1923 when Weston came into what would be his own. He had been to New York in 1922 to visit the aging guru, Alfred Stieglitz, and received approval for his new work, which was a tough-minded, tectonically articulate appreciation of the Armco Steel Mills in Middletown, Ohio. So it was in 1923 when Weston left his wife and children to travel with his lover, Tina Modotti, to Mexico, where they remained for the next three years.

He also was leaving behind his old way of working, abandoning the soft focus, restrained gray scale of pictorial imagery for a more declarative modernism. This also was a vital period in Mexico, a revolutionary time for the arts and culture, with great humanist expression from Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Frida Kahlo, and Miguel and Rose Covarrubius. In 1926, Weston finally returned to family and home in California; it was his 40th year. In 1928, he opened a San Francisco studio with his son Brett, and then moved to Carmel, where he remained until his death in 1958.

Weston was born in 1886 in Highland Park, Illinois, near Chicago, where he grew up. He began to photograph at the age of 16 after receiving a Kodak Bull’s Eye #2 camera as a birthday present from his father. His first photographs captured the parks of Chicago, where he lived at the time. An indication of how seriously he took this beginning is his commemoration of his 50th anniversary in photography in 1952 with a special portfolio.

In 1906, Weston photographed professionally in Chicago and California; he attended the Illinois College of Photography in 1908. He worked in California as a door-to-door portrait photographer or as a studio printer. He married Flora Chandler in 1909, a wealthy woman seven years his senior; her father was successful in real estate and later became publisher of the Los Angeles Times. Edward and Flora quickly had four sons, Chandler (1910), Brett (1911), Neal (1914) and Cole (1919). Between 1911 and 1922, he operated his own portrait studio and made pictorial salon images, successfully entering international competitions and exhibitions. With many, Weston perceived the shifting tenor of culture at the end of World War I. The case for fine art photography had been won; it was a time to see more clearly and understand more directly. Photography, rather than trying to be richly connotative, should depict “the very substance and quintessence of the thing itself,” Weston declared.

Through the 1930s, Weston enjoyed publication and significant exhibition, work with the WPA Federal Arts Project in New Mexico and California; and in 1937, the first Guggenheim Award made for photography. In 1938, Weston married Charis Wilson, with whom he had lived and photographed since 1934. She is the model for much of his work during this period, and together they published two books, The Cats of Wildcat Hill and California and the West. They were divorced in 1946.

Weston was a founding member of Group f.64, which included California-based artists Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham and Willard Van Dyke. Suffering from Parkinson’s disease, Weston ceased exposing photographs in 1948. His sons Brett, then Cole, took over printing his work for him. In 1955, Brett took on a project to make eight prints each of 1,000 negatives Edward selected. These were called the “project prints,” and about 800 negatives were realized. He died on January 1, 1958, in Carmel.

George Eastman House holds more than 250 prints by Edward Weston, including a collection of personal images he made with Tina Modotti in Mexico. Gustavo Lozano, an Andrew Mellon Fellow in the advanced residency program at George Eastman House, has been studying the Museum’s Weston holdings. He reports that during his formative years in the 1910s and early ’20s, Weston’s photographic technique was influenced by the dominant Pictorialist aesthetic of the moment. His photographs from that period were printed by contact on matte platinum, palladium or gelatin silver paper. Later starting around 1922, Weston progressively abandoned his romantic, diffused aesthetic and shifted towards a more objective form. He began using sharper lenses, a large format camera with sharp focus in every plane and printed (still by contact) on smooth, glossy gelatin silver paper without retouching.

Lozano, formerly the photography conservator at the National Library of Anthropology and History in Mexico, observed that Weston’s lenses were a very expensive anastigmat and several soft focus, among them a Wollensak Verito and a Graf Variable. George Eastman House has in its collection a Rapid Universal Lens (Bausch & Lomb Optical Company, Rochester, New York) inscribed, “To Brett – Dad ’37.” Weston made use of a 3¼ x 4¼ Graflex camera, a 4 x 5 RB Auto-Graflex and an 8 x 10 Eastman View No. 2D.

The inscriptions in Weston’s prints changed over time, Lozano notes. In his prints from his early works until the ’20s, Weston signed in full, dated and inscribed his prints with pencil below the photograph and sometimes along the bottom edge on the mount. In his late works and particularly in his last two big projects, the “50th Anniversary Catalog” and the “Prints Project,” the full signature in script is transformed into the printed initials “EW” and the date, and the title was no longer included.

The Weston legacy has been that of carefully rendered, finely printed work without complex manipulation. Weston’s style was to use simple materials very well. It is an axiom that has sustained his regard into our time.

Anthony Bannon was the seventh director of George Eastman House, the International Museum of Photography and Film in Rochester, New York.

By Anthony Bannon

Frederick Henry Evans was a little man whose photographs from the turn of the 19th into the 20th century play, to this day, very, very big. They are images that do honor to the grand places of their making—cathedrals notably among them—and do honor to the light that is found there.

Frederick Evans seemed an odd, small man in his orange corduroy jacket and his green tie secured by a scarab ring, looking intently through thick spectacles. But the images he made, elegantly understated through platinum prints and meticulous composition, were sober, rich statements made special through painstaking visualization before and after the shutter opened.

He was a bookseller, but no ordinary one, as accounted the great playwright and customer, George Bernard Shaw. His place on Queen Street, Cheapside, London was “jam full of books,” Shaw recalled. “The window was completely blocked with them, so that the interior was dark: you could see nothing for the first second or so after you went in, though you could feel the stands of books you were tumbling over.”

And then there was Frederick Evans himself. He was obstinate, opinionated, sometimes unreasonable and impatient, and, said Shaw, he would sell you not what you asked for, but what he thought was good for you.

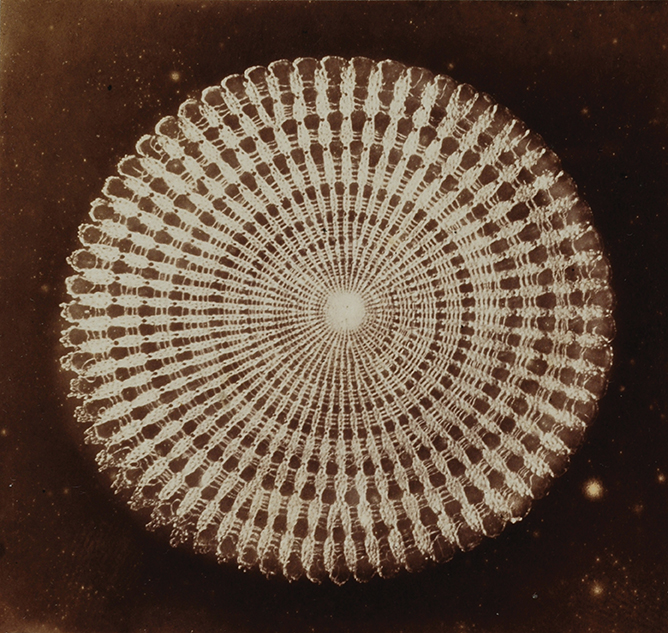

In 1898 he retired from the book business. Evans was 45 years old, and he set out to focus on photography, begun in the previous decade. He then had made images through a microscope of such as the spine of a sea urchin (Echinus), and he told colleagues at the Royal Photographic Society in 1886 that he pursued this new medium out of interest in the beautiful, taking pride in letting the materials of photography speak purely, without retouching or other intervention. His objective was to make “plain, simple, straightforward photography render, at its best and easiest, the effects of light and shade that so fascinate me.”

In his time, by 1900, he was acclaimed the master of architectural photography, and not simply a photography that created a record of a place, but a photography that moreover presented the ideas that stood behind the aspirations of place, whether the cathedrals at Ely, Wells, or Glouchester, or the home of the artist William Morris at Kelmscott, shortly after Morris’ death. Evans also had achieved respect for his photographic portraits, such as the intense study he created of the young illustrator Aubrey Beardsley, who frequented his bookshop. The Beardsley portrait in the George Eastman House Collection features a mount drawn by Beardsley, satyrs climbing a vine that entwines as ground for the photograph. It is one of more than 200 Evans images in the Eastman House collection.

In 1900, the Linked Ring Brotherhood, the fabled association of artistic photographers in Britain, elected Evans to their ranks. Evans also that year was married for the first time and had his first solo exhibition of 150 works with the Royal Photographic Society. In 1903, he was the first British photographer to show in Alfred Stieglitz’ journal, Camera Work. Stieglitz called him no less than “the greatest exponent of architectural photography . . . He stands alone in architectural photography, and that he is able to instill into pictures of this kind so much feeling, beauty, and poetry entitles him to be ranked with the leading pictorial photographers of the world.”

In the thick now of the new vigor felt by artistic photographers, Evans wrote widely and passionately about the new art, maintaining a stance on behalf of a straight photography, untended by manipulative treatments such as brushed on pigment and drawn-in accents upon the negative. He became secretary of the Linked Ring, selected and installed its annual salon for several years running, and enjoyed an exhibition in the gallery of the Photo-Secession at 291 Fifth Avenue in New York City. He made images, increasingly landscapes, for the magazine Country Life; he continued to exhibit in the fine art salons, galleries and museums; he illustrated with 11 photographs the 27-volume memorial edition of the works of the writer George Meredith for Constable and Co., a London publisher, and he ventured afield to depict mountains and rivers on the continent and informed the pictures with quotations from poetry and the Bible upon the image mount.

But as he grew older, Evans had difficulty carrying his equipment to a scene, and spent less and less time making images after World War I. By the mid 1920s, he had virtually stopped the practice that had been his passion for the past quarter century. Then the Royal Photographic Society elected him as an Honorary Fellow in 1928. Beaumont Newhall pointed out in defining text on Evans written in 1963 for a George Eastman House exhibition of the artist’s work: “He was then 75 and almost forgotten, and his friend J. Dudley Johnson, past president of the Society, had to remind the Council of the eminence of the candidate.” Evans died on June 24, 1943, two days away from his 90th birthday.

Karina Kashina, an Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in the Advance Residency Program in Photograph Conservation at George Eastman House, has researched the Evans’ images in the Museum Collection to find a variety of material treatments. While recognized as a master platinum printer, he also worked in silver gelatin particularly late in his career, using a variety of different papers, and also in photogravure, she noted. Important to his handling of the image was his multi-layered mounting system adopted from his friend, F. Holland Day, a Pictorial photographer who worked in London and New York. Evans’ mounts are framed with pencil and watercolor accents and appear in one, two, or three layers, including tissue. His signature also appears in many ways—his full name with middle initial in pencil, or in pencil repeated over in watercolor, with initials in pencil or in blindstamp on the mount or on the print, always in the bottom right corner.

In an essay in American Photographer in 1904, Evans advised photographers to “ . . . try for a record of an emotion rather than a piece of topography. Wait till the building makes you feel intensely . . . Try and try again, until you find that your print shall give not only yourself, but others who have not your own intimate knowledge of the original, some measure of the feeling it originally inspired in you . . . This will be ‘cathedral picturemaking,’ something beyond mere photography.”

Anthony Bannon was the seventh director of George Eastman House, the International Museum of Photography and Film in Rochester, New York.

Trending

-

Gallery Focus2 months ago

Gallery Focus2 months agoNew: Focus Magazine Returns To Print

-

Gallery Focus1 month ago

Gallery Focus1 month agoPreserving the Past, Capturing the Present: The Journey of Three Traveling Tintype Photographers

-

Gallery Focus2 months ago

Gallery Focus2 months agoNorthern Plains Native Americans: A Modern Wet Plate Perspective (Volume 2)

-

Collector's Focus1 month ago

Collector's Focus1 month agoFine Art Photography and the Human Condition: A Study of the Emotional and Psychological Themes in Contemporary Photography

-

Gallery Focus1 month ago

Gallery Focus1 month agoExploring the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Photography: New Possibilities and Challenges

-

Gallery Focus1 month ago

Gallery Focus1 month agoState of the Arts: The Market For Fine Art Photography

-

Gallery Focus1 month ago

Gallery Focus1 month agoUnleashing Creativity with the Art of Polaroid SX-70 Emulsion Lifting

-

Gallery Focus1 month ago

Gallery Focus1 month agoPainted Smiles and Hidden Tears: A Photographer’s Journey into the World of Circus Clowns