Photographer Focus

Arthur Tress: Finding Us In The Other

Published

1 year agoon

By James Rhem

When Arthur Tress stood amid the sumptuous retrospective of his career in the rooms of the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. in July of 2001, he had one question: “Where do I go from here?” At 60 Tress was not ready to end his career as one of America’s most prolific and protean photographic artists, but he wasn’t ready to settle into repeating himself either. “It happens to many photographers,” says Tress, “ you become successful for one period because maybe in your twenties and thirties you make a certain contribution to photo history and then you kind of settle into that.” And, indeed, while he’s produced a huge and varied body of work, prints from Tress’s Dream Collector series done when he was in his thirties remain perhaps his most collected work along with his homo-erotic imagery and selections from one of his excursions into color photography and extended photo-narrative, The Fish Tank Sonata.

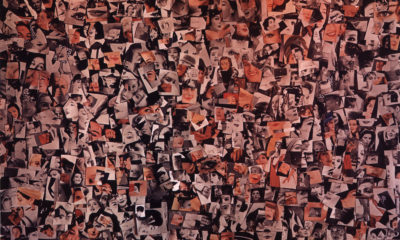

Tress describes himself as “polymorphous perverse” in style and motivation, always looking for the edge of expression and pushing it or transgressing at that edge just a bit. The last rooms of the Corcoran show contained what must have seemed to many viewers the end of the line in stylistic experimentation. There were “pop-ups,” three-dimensional photo constructions and a group of images called Faceted Fictions” These last Tress created by photographing book illustrations through a faceted glass and then hand coloring the photographs. “With this elaborate series of very crafted images, I really pushed what photography is normally thought of,” Tress recalled in a recent conversation.

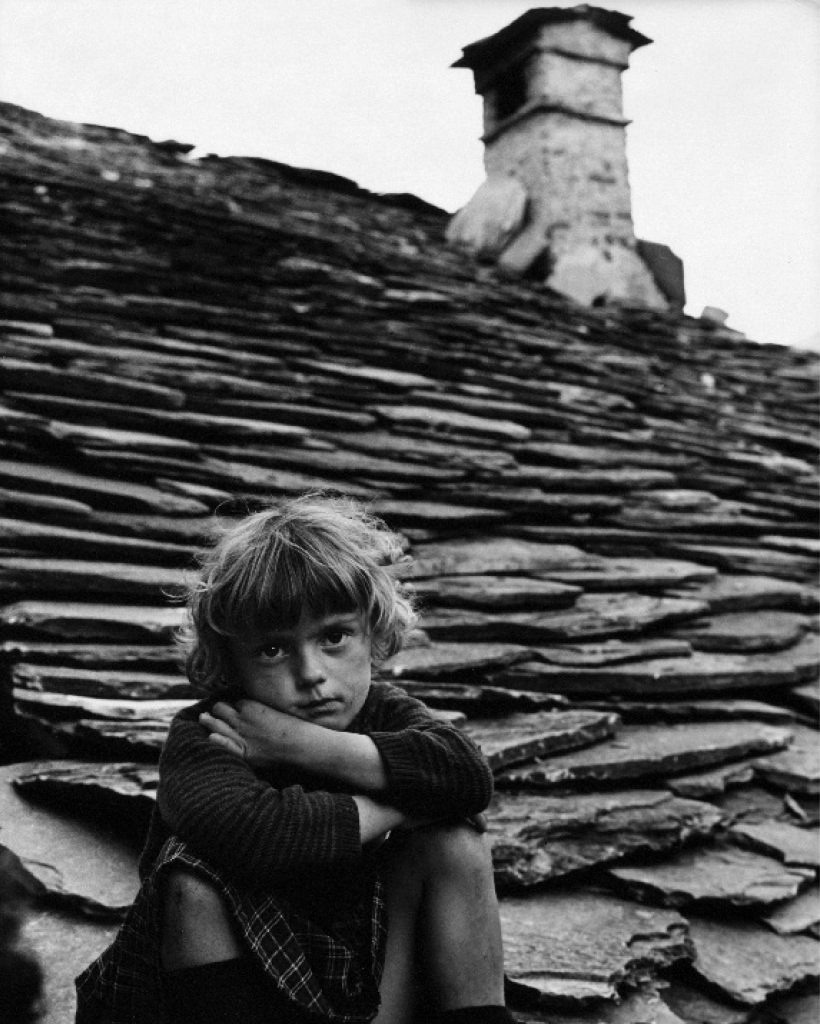

“So what do you do?” Tress continued. “You go two steps forward and one step back; so I took six steps backward. I began rereading, getting in touch with photographers that I admired in my youth like Henri Cartier-Bresson, Walker Evans, and others. I began looking at their books again. So in my own photography I went back to simple documentary, just walking around and taking pictures.” For Tress, known as a pioneer of “staged” photography in his Dream Collector and Theater of Mind series in the 1970s, this move was both a departure and a return. His first major work was also documentary made just “walking around” — Open Space in the Inner City: Ecology and the Urban Environment — a series undertaken for the Sierra Club focused on finding remnants of nature in the built environment. Five thousand portfolios of that work were printed and distributed to public schools. It fulfilled its documentary mission, aided in many ways by Tress’s darker surrealist sensibility.

Before Tress could get out the door on his new walking adventure, what he describes as a “funny event” happened: a heavy box of prints he was getting down from a high shelf fell on his head and gave him a slight concussion. Perhaps it was more than slight; he awoke that night with the room spinning and found himself taken by ambulance to the hospital. He developed a severe case of vertigo. Most vertigo lasts a day or perhaps a week; Tress’s lasted a year and a half.

The falling box was the first of a small series of accidents that had significant impacts on Tress’s new creative work. When he started photographing again, he began a series he calls Spinners created by rotating the camera lens around a central pivot during exposure. “I’d just twist my wrist,” he says. Spinners of children seem to catch them with a fresh visual energy not so much in a tableau from their dreams as in the visceral process of dreaming itself.

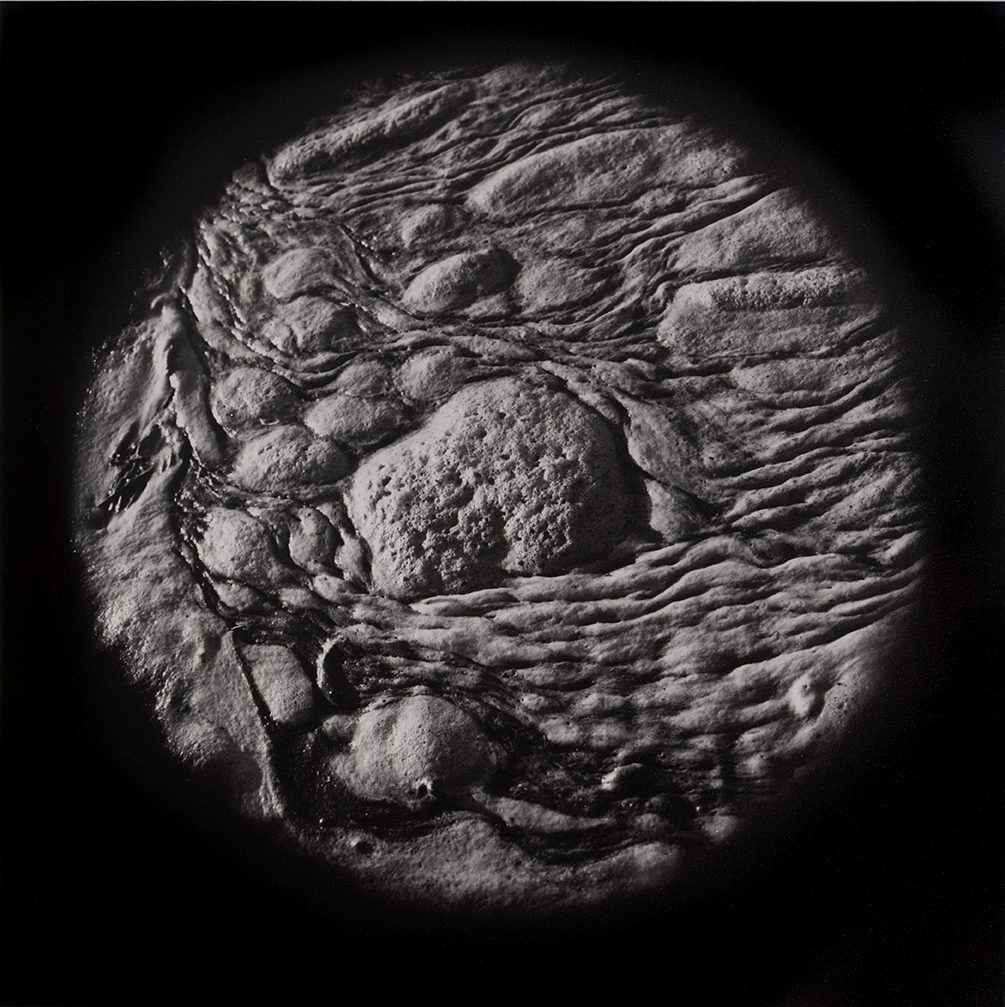

One day while making Spinners, Tress’s lens shade got cock-eyed. He thought, looking at the vignetting in the ground glass of his Hasselblad, “this is interesting” and went on to make a series of octagonal photos. Later that led him to wonder what would happen if he turned the lens shade around backwards. He tried it and looking at the fully circular vignette, he began to imagine images of strange new planets. Focusing on different textured and patterned surfaces, he created a whole portfolio of these, which Lodima has just published as a book. “I was just using what I found — a kind of ‘straight’ photography, not that that’s in anyway superior to manipulated photography. It’s just where my head has been the last few years,” Tress continued.

The vertigo, Tress says, created a little instability in his creativity and made him rely on intuition more than on a program of intention. Somehow it also got him into geometric shapes, especially spiral shapes.,

While the actual vertigo was new to Tress, the appeal of disorientation and the quest for reorientation were old friends. After college, he traveled the world — Europe, Egypt, Mexico, India, Japan and Africa — photographing cultures and customs as a kind of folklorist and ethnographer. Indeed, he ended his world tour in Sweden working as photographer for the Stockholm Ethnographical Museum. And when Tress retuned to the States in 1968, his first assignment took him to Appalachia to document the people and customs there. Each of these “foreign” worlds presented a disorienting aspect, a challenge to Tress’s understanding and experience, a challenge he would work out photographically by embracing the “otherness” of the places and peoples. He had, after all, long been in the process of embracing the otherness of his homosexuality, a process culminating in yet another body of published work, Arthur Tress: Facing Up (1980). “Growing up in the 1950s as a gay teenager and not really knowing what that was gave me sort of a sense of being an existential outsider,” he says.

The outsider hasn’t wanted to change, but he has thrived on transformations of the world around him. In the early 1980s Tress discovered a way into an abandoned training hospital on New York’s Welfare Island, a 500-room facility full of outmoded equipment from the 1950s. For three years he entered through a second-story window with cans of colorful spray paint, his camera and color film. He transformed over 60 rooms from haunting tombs filled with the memory of diseases like polio into what he describes as “Kafkaesque kindergartens.” An iron lung becomes The Green Cow; an array of portable respirators becomes a rainbow fantasy of maternal nurturance in Mother Matrix.

In some ways Tress has been almost as prolific, varied, and creative in the six years since his big retrospective as in the 40 years it showcased. He’s produced compelling work in at least ten new series in both black and white and color. In two of the most impressive, he’s played to his strengths as an “existential outsider” making penetrating images of two very contemporary subcultures — the habitués of skateboard and paintball parks. Both these worlds contain the fears and excitements that have animated some of Tress’s best work for years. “It’s something reflective of my inner psyche or insecurities, I guess,” he says. “I always seem to focus on this edgy darkness, and that’s where the best Tress lies. I don’t know why: it’s my gift and my curse.”

In the skateboard and paintball parks, the fears of death and injury are both real and imagined; the dreams of flying and conquest enjoyed equally though in miniature versions. But if thematic familiarity drew Tress to these worlds, it is perhaps his delight in engaging very different visual and technical problems that has helped make them newly vibrant. “Look, there’s a great joy in photography,” says Tress. “Most photographers, when they’re happy is when they’re trudging along with their camera photographing; it’s the brightest part of their day.”

Just as thematic streams in Tress’s creative life flow together in these two series in transformed ways, so, too, do formal visual qualities: the disorientation of the current spinners series, a harking back to the drama of shadows, which he once explored in a full-length narrative (Shadows, 1975). Yet nothing about the work seems old, rehashed Tress.

“An aspect of the skate parks and paintball series that I’m rather proud of,” says Tress, “is that I became a sort of sports photographer to do them, and that was something that I’d never really done. I really got good at anticipating action and shooting at 500th of a second. With the Hasselblad it’s not easy. By the time you focus and release the shutter the action may be over. The way I enjoyed learning these new skills was as a challenge, I think that’s part of me, the attraction to trying the new to see what that’s like. What can I do with that?”

Eventually the skateboard work became a kind of narrative of ritual self-initiation that will soon appear as a book — Wheels on Waves.

Serendipity has guided Tress’s artistic journey in the last several years, and while he’s opened himself to aleatoric practices at times (as in the “spinners”), there’s been nothing careless about how he’s traveled these new pathways. Take Pointers, another post-vertigo series that followed Spinners and the octagonal photos. Exposure to a lot of modernist, European-style architecture around Palm Springs caught Tress’s eye and led him back to reviewing Rodchenko and Bauhaus imagery. Faced with the challenge of photographing these stairways and facades in a fresh way, he turned the camera 45 degrees and stood his square image on its point. There was a touch of Mondrian influence hovering over the form as well, since Mondrian had done some diamond-shaped paintings with his usual geometric content. But Tress didn’t stop there: “It was a way of working that I’d never explored,” says Tress. “Over the last five or six years I’ve thought of myself as a kind of student, recharging my batteries for the next 25 years,” he says laughing. “When I was doing the Pointers, I even went to Europe to photograph some of the masterpieces of modernist architecture: Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, and others. I just made a little pilgrimage.”

About the Pointers Tress says, “I set out first to destroy the frame, the traditional frame of the photograph. I’ve made myself a little rule for the last few years that I’m not allowed to make the same photograph twice. I think a lot of photographers get one or two interesting photographs and then do that for the next five years. So I’ll do three or four of something, and then I’ll say to myself, ‘Have I done that already?’ In photography it’s very easy to get into visual formulas, and I think a lot of photographers fall prey to that. It’s the way you structure reality. You just get in the habit of organizing things again and again the same way.”

Though the modernist subject matter in the Pointers seems familiar, Tress’s images convey a fresh energy, one that not only satisfies in the here and now, but also one that renews one’s sense of what was fresh and vital in all that Bauhaus imagery and modernist design in the first place.

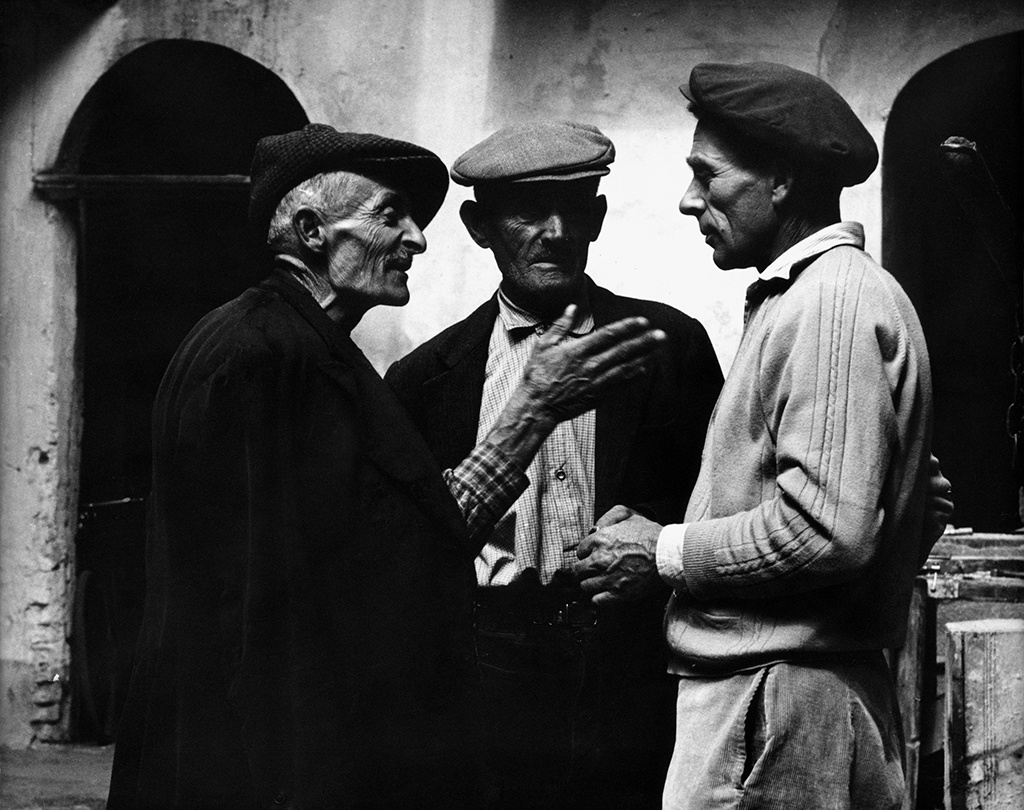

Influences abound in Tress’s work. He readily acknowledges them, knowing that to be influenced is not to be derivative. “A big influence on me in the last few years has been Paul Strand,” he says. “A couple of his books are laid out on my table right now.” Though Strand did all kinds of work, his portraits have impacted Tress perhaps most, and have led to yet another impressive series in the last few years called Grave Demeanors. A number of these picture gay men with their mothers. One astonishing portrait of Tress’s sister makes the idea of family connection almost literally palpable.

All of Tress’s recent work has been formally well structured; something that he believes may be a professional disadvantage for an artist these days. Thinking especially of his Pointers” Tress muses: “One of the tenets of modernism is movement of forms within the picture and the tension of positive and negative shapes and the edges of the picture, but now with the adoration of the snapshot aesthetic that attention to form has been neglected a little bit — the ability within that instant to be able to construct a very complicated orchestration of shapes and forms. I think we’ve dumbed down what we expect from photography. And sadly, I think a lot of curators have followed that lead.”

Though Tress has continually renewed himself creatively and produced an impressive body of varied work, he remains untroubled by the thought that clear, careful structure is passé. For him, a photograph could hardly aspire to the status of art without it, and, in that way, he remains unabashedly old-fashioned even as he goes forward never really repeating himself.

James Rhem is the author of Ralph Eugene Meatyard: The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater & Other Figurative Photographs and the Phaidon 55 Series on Aaron Siskind.

You may like

Today is the birthday of Berenice Abbott, an American photographer. A key figure in having brought photographic circles in Paris and New York together. She moved to New York in 1918, then to Paris in 1923, where she met Man Ray, who hired her as his photography assistant. Man Ray had introduced Abbott to the work of Eugène Atget. She devoted herself to documenting New York with the same dynamism that Atget had shown for Paris, photographing its streets, buildings, parks, and, of course, its people.

Photographer Focus

An Outsider On the Inside: Bruce Daivdson

Published

1 year agoon

December 25, 2021By

Jain Kelly

An intense and well–spoken man, Bruce Davidson has proved to be one of the most prolific photographers of the 20th and early 21st centuries. The list of his photographic series that have culminated in books is startling. He has published 16 book titles. A partial list includes East 100th St. (1970 and 2003); Subway (1986 and 2003); Central Park (1995); Brooklyn Gang (photographed in 1959 and published in 1998); Portraits (1999); Time of Change, Civil Rights Photographs 1961–1965 (2002); England/Scotland 1960 (2005); and Circus (2007). In particular, the modern classic East 100th St. has afforded Davidson a special niche in photographic history. With a background in what many would characterize as photojournalism (he is a member of Magnum Photos), he introduced innovation by utilizing a 4 x 5” view camera to create portraits with depth and complexity — and yes, beauty — of the residents of what was termed in the late 1950s “the worst block in Spanish Harlem.” The impact of East 100th St. was heightened by the charged emotional atmosphere of a nation struggling with Civil Rights issues.

Bruce Davidson is known as an artist whose work ethic is unusually consistent. He invests a great deal of thought in his projects before he begins, but that is only half the equation. The other half is sheer, non–stop work over extended periods of time to accomplish his goals. His approach requires an extreme level of organization, right down to the careful filing of prints. He brings that same work ethic and organizational ability to the presentation of his exhibitions in the art world. Although a veteran of the museum world — his first one–person show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York took place over 40 years ago, in 1963 — he has come to the art gallery scene relatively recently, in the 1980s. In a short period of time he has emerged as an important figure in the collectibles market, partly because his body of work is large enough to sustain exhibition after exhibition in rapid succession. It is notable that in addition to investing time in preparing exhibitions and arranging his archive of past work, he still moves forward with the act of photographing the present and planning future projects with joyful intensity.

At the time of this interview, The Jewish Museum in New York City is presenting Isaac Bashevis Singer and the Lower East Side: Photographs by Bruce Davidson. Spanning the years 1957 to 1990, the exhibition features 40 intimate photographs of Singer, the revered Yiddish author, as well as residents of the Lower East Side Jewish community, including visitors to the Garden Cafeteria in that location. Could you tell us a little about your relationship to both Isaac Bashevis Singer and the world of the Lower East Side?

Isaac Bashevis Singer lived in our building here in New York on the fifth floor. I had photographed him years before on a magazine assignment. We just became neighbors. Also, I was interested in trying to find out about his world because that was the world of my grandfather. I wanted to find continuity. My grandfather came to the United States from Poland as a boy of 14. He learned English, became a tailor, and had a very good business. He went from being a tailor into manufacturing with his older son Leonard and Leonard’s wife Ruth, and that company is very large now.

I was born in 1933 and grew up in Oak Park, Illinois. My mother was a single parent. She was working in a torpedo factory during World War II. My brother and I could really fend for ourselves. We were very self–sufficient. We learned to cook. We learned to clean. We learned to meet our mother on time at the bus stop and carry home very heavy packages of groceries. My younger brother became an eminent scientist. I became a photographer. That was all part of being with my grandfather. For a while we lived with my grandfather in the home my mother was raised in. I began to sense there was something strange about my grandfather, there was some secret. There was something he left behind and he never really talked to us about it.

I was the first son in our family at that time to be Bar Mitzvahed. Our synagogue was a small clubhouse synagogue. I mean it was not a synagogue at all; it was a clubhouse with a small congregation. While I was reciting the Hav Torah during my Bar Mitzvah, I could see a box that I knew would be a camera on the rabbi’s desk. During the 1940s, cameras were scarce. Film was scarce. I had been taking pictures since the age of 10, and was very excited about receiving my first good camera and two rolls of film.

I was taking pictures and my grandmother emptied out a closet in the basement where she stored bottles of jelly. I began developing and making small contact prints in it. I even wrote on the outside of the jelly closet — I mean, it was small; I could barely fit in it — but I wrote “Bruce’s Photo Shop.”

You know, there is a similarity between photographing and tailoring. You learn to make the pockets straight, and actually you have the persona of the person you are fixing the jacket for. The persona is definitely there. It’s craft. And photography has craft also. So my grandfather sewed buttons and I sewed photographs.

So I would say that entering the world of Singer and the Lower East Side was really entering the world of my grandfather, but I am in no way an observant Jew.

As a Midwesterner transplanted to New York, you have demonstrated your great love of the city and its inhabitants in many series of photographs. Could you expand on your feelings about New York and how the city inspires you?

The town of Oak Park was a very small community. It was the home of Frank Lloyd Wright and Ernest Hemmingway. I have said that I am not a practicing Jew, but I am in the sense that wherever I photograph in New York — or wherever I photograph anywhere — it becomes to me a spiritual space in that I think there is a solemn responsibility when you have a camera. Although I don’t read the Torah, I do read the Torah of life, and my own personal Torah, so it wasn’t a big deal to leave Illinois to come East, to go to school, and to explore New York. My very first day in New York — my mother had remarried and we were staying at the Plaza Hotel — I began to explore. I went outside the hotel and I was photographing the pigeons and people with my Rolleiflex. My mother or my stepfather came out and said, “You’re using up all your film.”

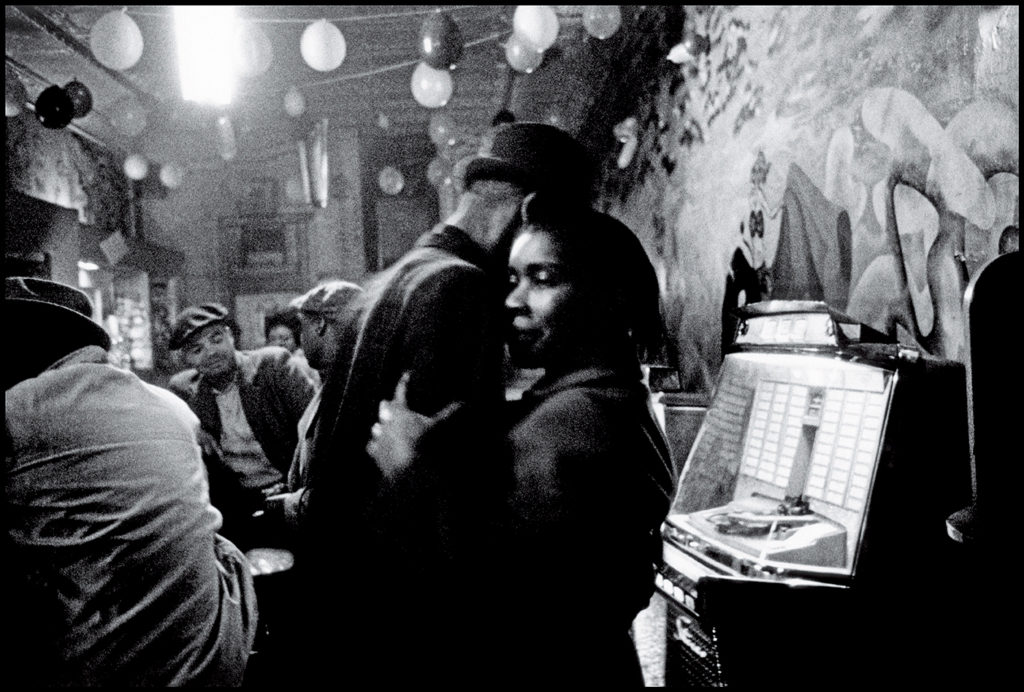

I think New York is probably the most important and the most alive city in the world. It’s the most diverse. It’s the most difficult. It’s the most challenging. I have found that over the years I have been able to enter worlds within worlds in the city, beginning with the Circus series, then the Brooklyn Gang, and later the Subway and Central Park, and other entities. I entered worlds within worlds and they became sacred places for me. I no longer entered a shul; I entered the sacred space of people’s lives.

You attended the Rochester Institute of Technology (1951–54) in Rochester, New York and Yale University (1955) in New Haven, Connecticut. In other interviews, you have spoken of taking classes at Yale with the artist Josef Albers. Can you tell us about that?

Yes, I took Josef Albers’ color course. I also took his drawing course, although I didn’t draw. I was there as a photo student. But his color course really left an impression, and I began to understand the meaning of color. That isn’t to say I was going to use color to become a color photographer. I understand color. I know how to use color, but I do not prefer it. I prefer black–and–white. My films are in color, but the Subway body of work is the only major body of still photographs that I have in color, except for a number of landscapes made on Martha’s Vineyard over the years.

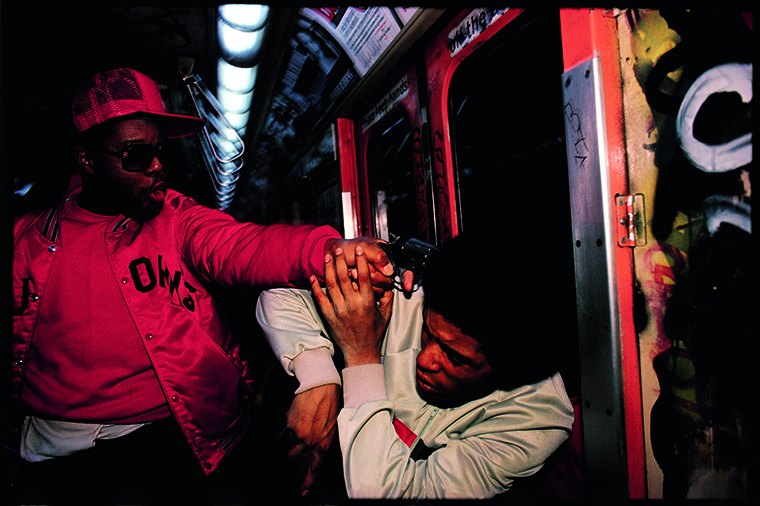

I started photographing the subway in 1979 or 1980 in black–and–white, but I saw another dimension of meaning in color. The graffiti, even the iridescent, fluorescent lighting in the subway, all had a kind of meaning — there was sort of a poisonous green–blue light down there that had color meaning, so I switched. I remember going out at day with one camera with color film and one camera with black–and–white, and I redid each picture. I would take pictures in black–and–white and then I’d switch to color. There’s a difference, you know, not only because one is black–and–white and one is color. There’s a difference in the “moment to moment” and you have to choose.

You have compared the subway to the Theater of the Absurd. Do you still think of it this way?

Yes, but it is also the most democratic space in the world. Anybody, rich or poor, healthy or unhealthy, rides the subway. The graffiti at the time was written all over the place and was what is called the hieroglyphics of anxiety, of anger, of frustration, of “I am invisible but my marking remains.” You know, dogs pee on a pole but graffiti artists draw their name. The dog says, “This is me. I am here.” They’re making their marking and then somebody else comes over and pees on that marking and makes a new marking; so that was the dynamic. But the subway could be excruciatingly beautiful. It could be the sexiest environment I’ve ever been in; we can’t go into details but the subway can really be sexy.

How did all this relate to the mood of the city at that time?

At that time, about 1980, the trains were running poorly. They were very unsafe, there were a lot of muggers, there was graffiti written all over the place. I think the city was in default at that time, also. It was a chaotic, neurotic, pathetic time. And I chose…the subway really chose me. I started to go into it with a camera out, with a flash. A safari hunter. In fact I fashioned myself after the tiger hunter Jim Corbett. His books were written for boys but I liked them. So I became the tiger hunter. When you hunt tigers you have to watch your back. Anyway, I had all sorts of fantasies going because that’s what the subway can be. It could become as sacred as a church pew, it could be beautiful, it could be upsetting, it could be depressing. Anything goes, and I fed on that.

You have stated that your work in the subway was an antidote to depression. How was that so?

Because the subway was more depressed than I was. And in photographing in color — I wanted the color to be vibrant — I drew a parallel between fish in the deep sea where you see no light and yet you have iridescent colors when light is shown on them. I wanted to transform the subway in some way so that from a beast I made it beautiful and when it was beautiful I made it bestial, so that anything could come to me or reflect off me and rebound in the subway. I left my imagination and awareness open to the moment. The color experience was also a human experience.

Did you find it an experience of loneliness?

Yes, I seem to be attracted to things in transition, things that are isolated, maybe alone. I gravitate to that which has a certain tension because it’s in transition. The circus was in transition from tent shows to coliseum shows, from small, intimate family circuses to large extravaganzas.

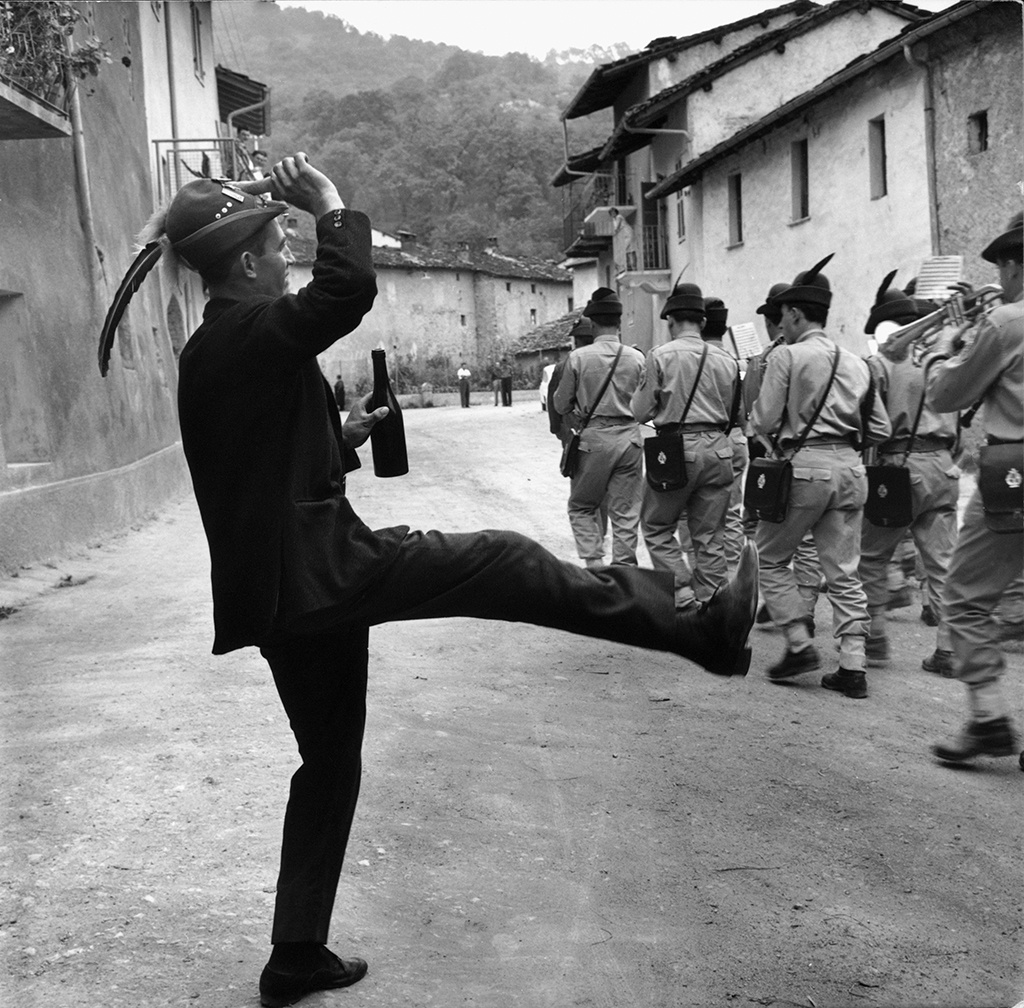

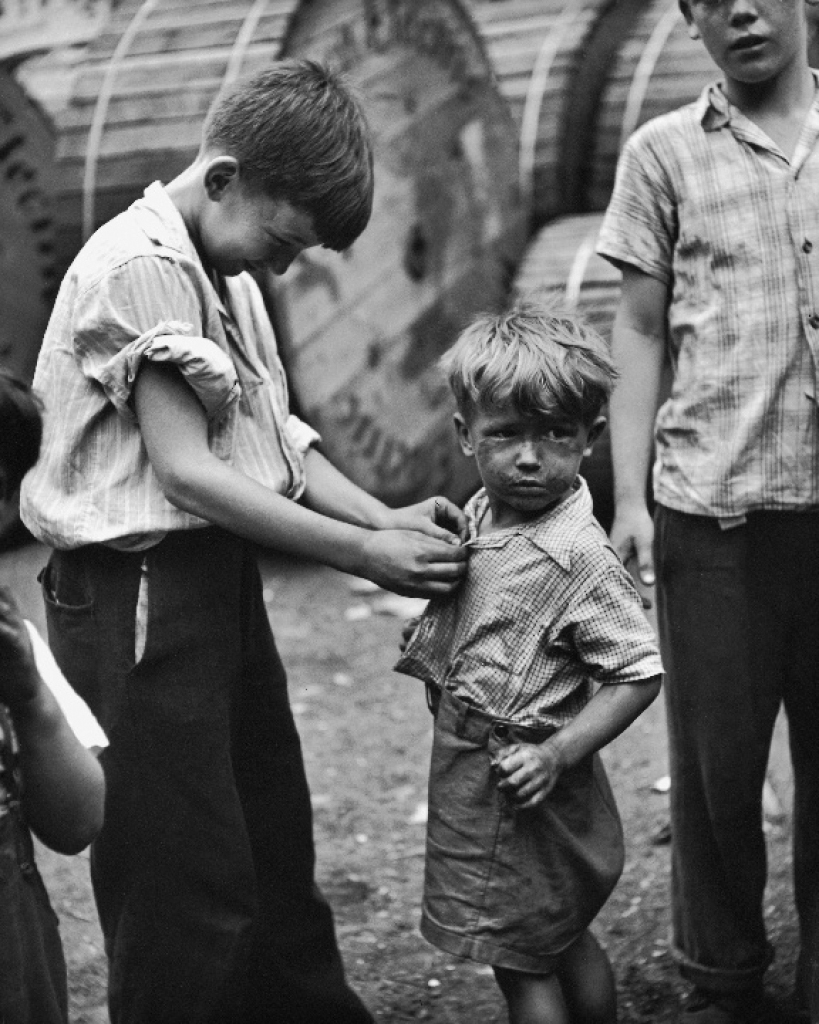

Let’s talk about your circus photographs. Historically, many artists of the 20th century, such as Pablo Picasso, Alexander Calder and Edward Hopper, have been drawn to clowns and the circus. What do you think is the source of the appeal and how did you yourself get started with the circus?

Magnum in New York had an incredible picture librarian by the name of Sam Holmes. Sam was an amateur trapeze artist. He was the one who told me about the circus in Palisades Amusement Park in New Jersey, which was the beginning of my circus work in 1958. I was not drawn to the circus per se, but to the clown who was a dwarf. It was the combination of attraction and repulsion that I felt standing next to him outside the circus tent that drew my attention and sustained a friendship with him.

His name was Jimmy Armstrong. He was melancholy. He was sensitive, very sensitive to everything. He wasn’t depressed but he was poetic. It’s almost like he was a performance artist. Even when he was outside the tent, he was performing; he was directing the camera to what he could feel at the time. I never said, ”Jimmy, why don’t you pick up your trumpet and blow it.” I waited for him to do it. He worked hard in the circus. He was carrying two heavy buckets of water. And you know, people in the circus liked him. I have a picture in the Circus book of a roustabout giving him a massage. He didn’t have to do that. But that was the nature of the circus, too — they were a family. They were kind of like Magnum, but with elephants.

Jimmy and I had a very silent friendship. I just observed him. He allowed me to observe. He also allowed me to see things that might have been embarrassing for him, or even dangerous, like walking through a crowd of children. You know children can be quite cruel to dwarves. Where else can you find someone with the same size head as your father, but half your size? At the end of our two–month trip together I bought him a Yashica Rolleiflex–type camera that he could hold in his hand. He often said that I was his best friend, even though I wasn’t really close to him, except in the sense that I was with him all the time. What made it so compelling was that we all have a dwarf in us, and that dwarf can come out in various ways: something small and compressed as being repulsive.

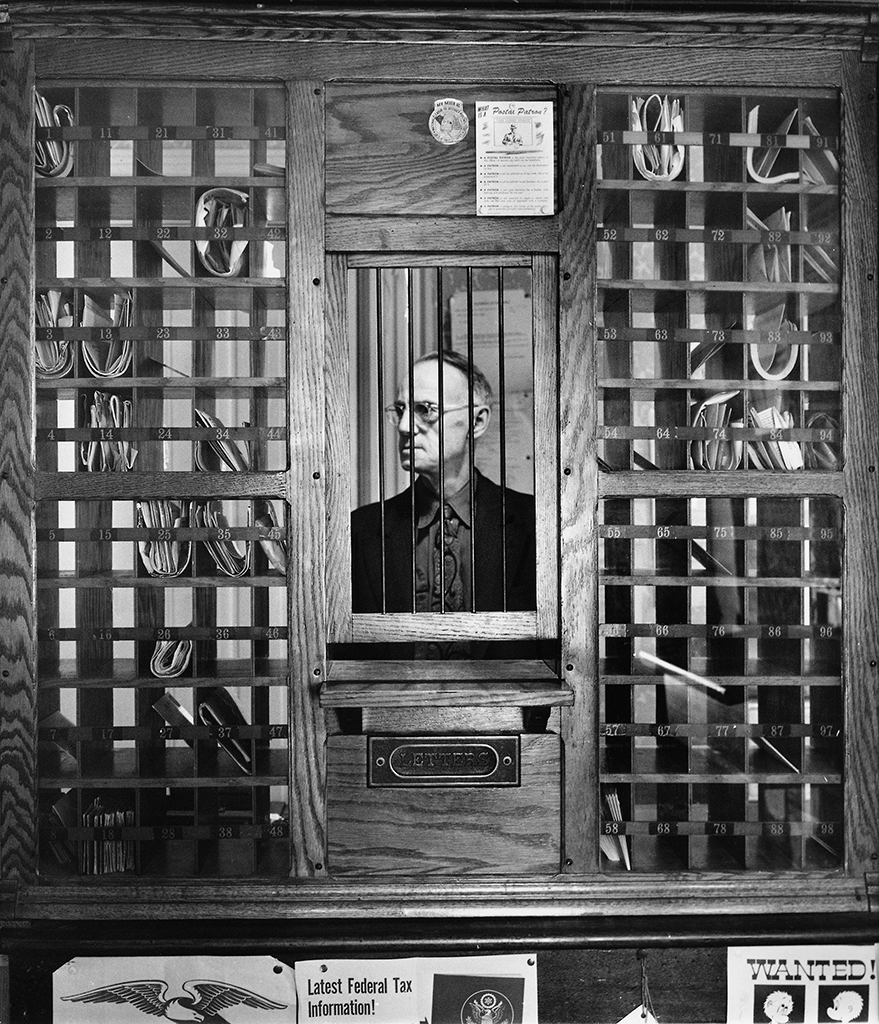

The picture I took of him peeking out of the van [on the cover of Focus Magazine] is an early ”confrontational” photograph. It isn’t that other photographers hadn’t done confrontational photographs, but it was something that wasn’t usually done. In photojournalism at that time you were supposed to be the “unobserved observer.” So no one looked at the camera because the camera wasn’t “there.” Here I made the camera “there.” I think that was a very penetrating thing. The fact that Jimmy Armstrong, the clown, allowed me that close into his soul was important to me.

He was married and had children. He married a normal–sized, but short, woman named Margie. Jimmy is dead now, and Sam and I can’t seem to find Margie. Sam found out that Jimmy, during World War II, could crawl into the fuselage of the bombers to do wiring. So he joined the war effort as a dwarf. He had a lot of lives. He was a musician. He was photographed by many different photographers, including André Kertész. He was even in a movie, Cecil B. DeMille’s The Greatest Show on Earth (1952) with Charlton Heston and Betty Hutton.

After I left the circus, he sent me a route card every once in a while. This was his schedule, so I knew where he would be. I would call the chief of police of a town and say, “My cousin is a dwarf in the circus. Could you get a message to him?” The chief would assume that I was a dwarf too, and he would jump into his car and run out with the message, “call me,” or whatever. Over time I lost track.

Going back to the period of your life following Yale, you were in the military from 1955 to 1957. Was there anything about that experience that relates to your photographic work?

Absolutely. In the army, I was in the Arizona desert for about a year. I used to hitchhike to Nogales, which was only 40 or 50 miles away, to photograph the bullfights. Patricia McCormick was a female bullfighter and I became somewhat friendly with her. In hitchhiking to Nogales I came upon a small town called Patagonia. It was really a railroad siding and a bar and a gas station and a post office and that was about it. There I met an old guy who was driving a Model T Ford and we became friendly. He was a miner. Every weekend I stayed at his bunkhouse and photographed. As I look at that body of work now, it seems very whole to me and I find it amazing.

It was the precursor to the Widow of Montmartre, which I made the following year, when I was transferred from Fort Huachuca, Arizona to Paris, France. There I met a French soldier who invited me to have lunch with him and his mother in Montmartre. After lunch I was standing on the balcony with my Leica and I saw an elderly woman hobbling up the street. I took a picture. The soldier said, “Oh, that woman lives above us and in fact she knew Toulouse–Lautrec, Renoir and Gauguin.” She was in her 90s in 1956, you see. She was the widow of the Impressionist painter Leon Fauchet. So the soldier introduced us and that series became the Widow of Montmartre. I lost track of that soldier for many years, but recently found him. He still lives in the same area. He’s one of the painters at the top of the hill in Montmartre.

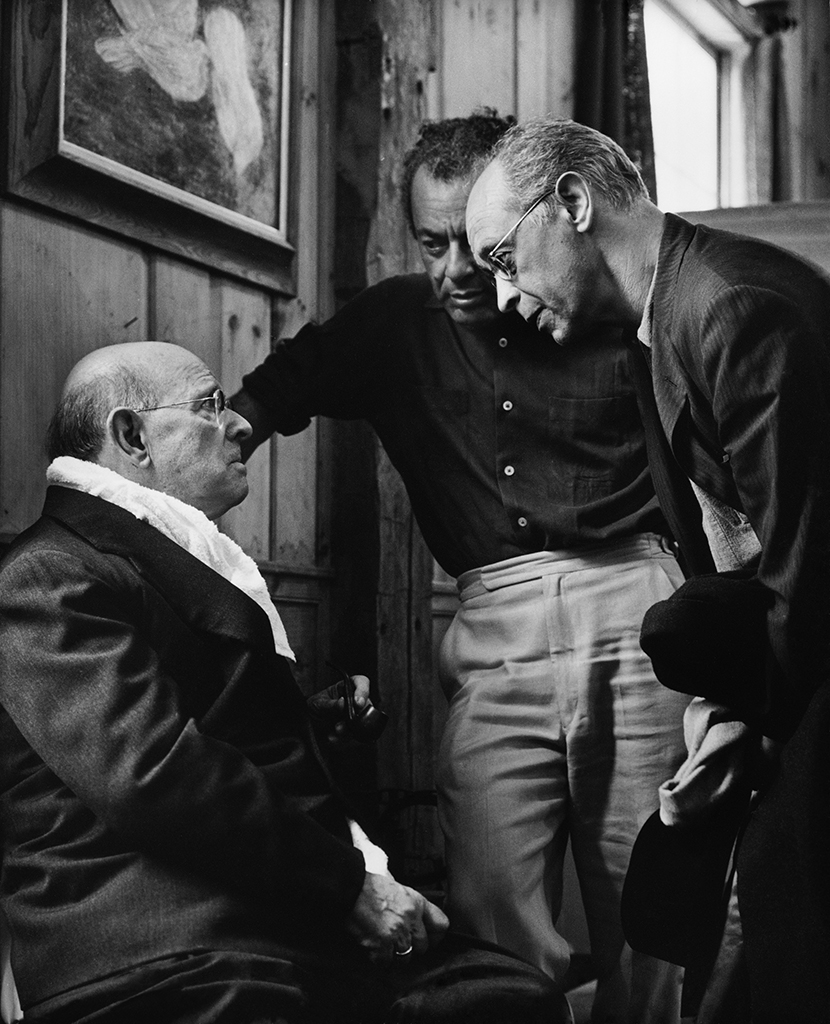

At that point in my life I decided to show my work to Magnum Photos in Paris and to Henri Cartier–Bresson. Well, actually I had no idea of Cartier–Bresson. He was beyond reach. I left my photos at the Magnum office. They called me and said, “We would like to show your work to Cartier–Bresson.” Then I had an appointment with him, and that was the beginning of my career, and my life in photography.

Henri Cartier–Bresson is known as one of the most influential photographers of the 20th century. Could you talk about the effect of Cartier–Bresson on you and your work?

Cartier–Bresson took me under his wing. He tried to get me to read more, to reflect more, to be more disciplined. Over that year we had a professional relationship in which I occasionally showed him my work. Of course he had seen the Widow of Montmartre contact sheets. In fact, I just donated those vintage contact sheets from 1956 and about 17 prints to the Fondation Cartier–Bresson in Paris.

Cartier–Bresson is known for developing the concept of the Decisive Moment, one definition of which is the moment of stillness at the peak of action. Do you see yourself as being influenced by the idea of the Decisive Moment?

Well, the concept of the Decisive Moment has never been absolutely clear to me. To me it’s the Decisive Mood, and not the moment. I think that, sure, there is a decisive moment in life in everything we do. There’s a certain timing. But it isn’t just about timing, a man jumping over a puddle. The Decisive Moment is an internal thing. If you become decisive and you enter life in a decisive way, the moments will appear, as long as you are in tune. So what we are really talking about is a way of looking at life, a kind of balance. Sure, there’s geometry, there are moments and all that, but my photographs are more of a mood and they are cumulative, too. They aren’t just one picture.

We’ve spoken of Cartier–Bresson. You’ve also mention in other interviews being influenced by W. Eugene Smith and Robert Frank. In an interview with the Oregonian Newspaper you said, “Cartier–Bresson was Bach, Smith was Beethoven, and Frank was Claude Debussy. They’re all in my DNA.” Could we discuss this?

Well, definitely Smith was an influence because his photographic essays published in Life Magazine were very powerful. I don’t see how anyone could do a better job on Spanish Village than he did. All his works were very theatrical. They’re almost like stage sets. I don’t think he’s given enough credit for what he’s done. To some extent I was influenced by Robert Frank, but I moved away from him completely when I did East 100th St. and, in fact, I moved away from almost everybody who might have inspired me when I did East 100th St..

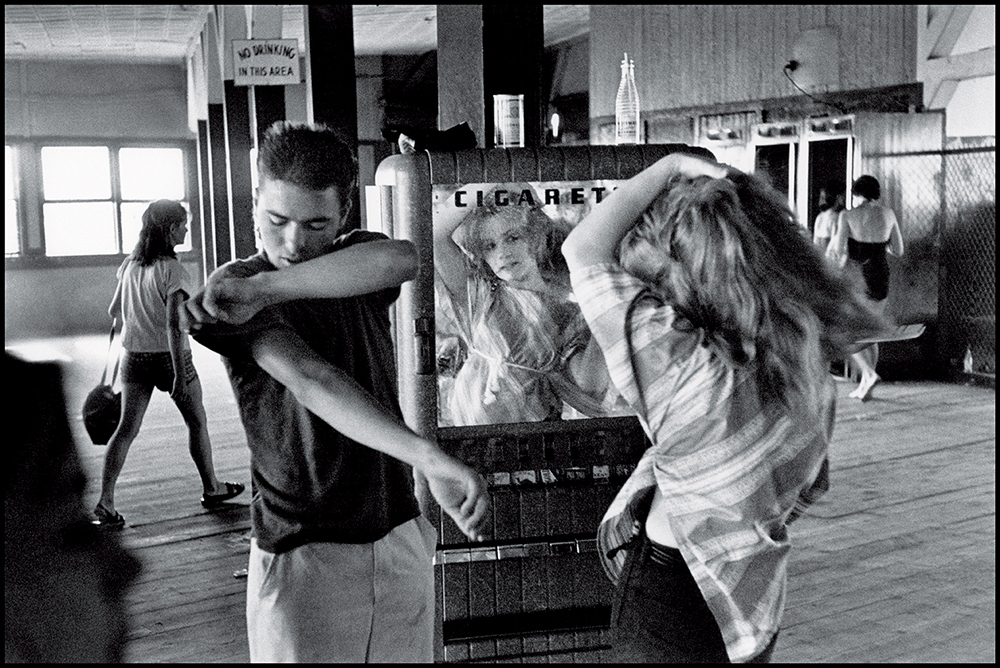

You did your series on the Brooklyn Gang in 1959. It was published in Esquire Magazine that year, but it did not appear in book form — Brooklyn Gang, published by Twin Palms — until 1998. One critic has described the essay on the Brooklyn Gang as having an air of innocence about it. Do you agree with that?

Those kids, at that time, you see, were actually abandoned by everybody, the church, the community, their families. Most of them were really poor. They weren’t living on the street, but they were living in dysfunctional homes. It’s the same thing. Anyway, they were kids and the reason that body of work has survived is that it’s about emotion. That kind of mood and tension and sexual vitality, that’s what those pictures were really about. They weren’t about war. I mean, you can’t compare those kids to the kids today who have machine guns. So there is an innocence in the photographs because it reflected the kids’ innocence, but that innocence could erupt into violence.

It’s interesting that the leader of the Brooklyn Gang, Bengie, who is now 65 years old, called when I was given a large show of the Brooklyn Gang at the International Center for Photography (ICP) in New York in 1998–99. My wife and I went down together and had coffee with him in midtown, and he turned out to have had an extraordinary life. He is now a substance abuse counselor. We just returned last Sunday from his birthday party, where we saw some of the old gang members.

What caused him to contact you?

There was a reunion of the old gang members. They were looking at my photographs in Esquire Magazine and they started talking. Bengie said he had been trying to get up the courage for years to call me, and finally he just did.

Perhaps we could discuss East 100th St. for a while. You photographed on that block from 1966 to 1968. The book East 100th St. was published by Harvard University Press in 1970, and was reissued in an expanded edition by St. Ann’s Press in 2003. You received the first–ever photography grant from the National Endowment of the Arts in 1966, which you used in support of the East 100th St. project. East 100th St. appeared as a solo exhibition — your second at this venue — at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1970. How did you come to be introduced to the people on East 100th St.?

Sam Holmes, the picture librarian at Magnum who told me about the circus in Palisades Amusement Park, also told me about the “worst block in Spanish Harlem.” His cousin was a minister living on the block and working with the Metro North Citizens’ Committee. So I looked up the minister and had an appointment with the Citizens’ Committee and then I photographed for two years.

Were you attempting to create collaboration between the photographer and the subject?

Yes, one of the reasons I chose to use what would be regarded as an old–fashioned view camera on a tripod, with a flash, was that I felt it dignified the act of photography. I was eye–to–eye, face–to–face with the subject. The only thing that connected me to a camera was the little cable release, but I was really looking into the eyes of my subject. The environment was also important; what surrounded them was part of the picture, too. It was part of their expression. If the wall had a picture on it or a birdcage or nothing, it said something about them.

In some of the photographs the people presented themselves in a middle class way, very dressed up. Why do you think they chose to do that?

Well, you know, people are middle class in their minds. They may not own an automobile, but they dress very elegantly on Sunday, going to church. I had an experience in which I saw some children half–naked. They just had some little panties on and they were playing on the fire escape. I went to take that picture. The mother saw me and brought the kids in through the window. I counted the floors and went up and knocked on the door. The woman said, “You can photograph my children that way, but you must also photograph them dressed up.” So I photographed them playing on the fire escape and on Sunday I photographed the family dressed up.

Much has been made of the dark tonality of the photographs in East 100th St.. Did that tonality emerge immediately as your intention, or did it evolve over time?

When I entered a person’s home I was entering a sacred space, is the way I looked at it. It was up to the person to decide where the photograph might be made. Was it in the kitchen, in the bedroom, or in the vacant lot downstairs? Most of the time it was in the bedroom because it was a quiet space and it had artifacts or clues to their spirituality, like a cross, a picture of Jesus, a framed photograph of John F. Kennedy. Very often these dwellings were dark. I remember a photograph I took of an elderly woman sitting on a bed with towels and rags stuck into the cracks in the window to keep out the cold air. That was an important part of the photograph, which showed her sitting alone in this dark room with only one little light bulb on the ceiling. I tried to be true to the mood, to the darkness, and through the darkness I made a light because I made an image of that person’s predicament in life. So when I printed the photographs for the book I printed them in a very strong and heavy way. In fact, I was inspired by the bronze Degas sculpture of dancers at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The bronze looked like shrapnel to me. It was dark, metallic, rich, and I followed that through as a theme in the printing of my photographs. I was highly impassioned in those days with that tonality. Years later, when I was printing for the second edition of East 100th St. I opened up the tonality because I was able to: the technology had improved. I had the aid of a scanner. I made the printing a little lighter.

East 100th St. wasn’t just a documentation. It was a vision, a vision in which I reached into the tonality with a large format camera. I wanted that depth of field. I wanted to be able to see down to the street while someone was lying on the couch. The way the camera was used, the way the lighting was used, the way I saw things were all part of the aesthetic. The aesthetic dimension to East 100th St. combined with the sociological message.

How recently have you had contact with the people on the block?

A few years ago I received a fellowship from the Open Society to go back to photograph. When I returned I could find very few people I knew. They had moved on. You know, people move on. What happened in the 1960s was that a matrix of new schools, tutorial programs, all kinds of things, rippled all through Spanish Harlem. Metro North Association was the beginning of that self–improvement, reviving the community. The community itself was doing it. I photographed positive aspects of new schools, new housing, tutorial programs, a new park and ball field, a women’s health center, the vest pocket gardens, and the new mood and the street. I’ve donated all that work to the Union Settlement and it is on display there. Yes, Spanish Harlem has changed. It’s almost easier to get a café latte now than a café con leche. Some of the texture is lost, but it’s a lot safer than it was.

Obviously you maintain contact with people you have photographed over the years. Can you tell us more about that?

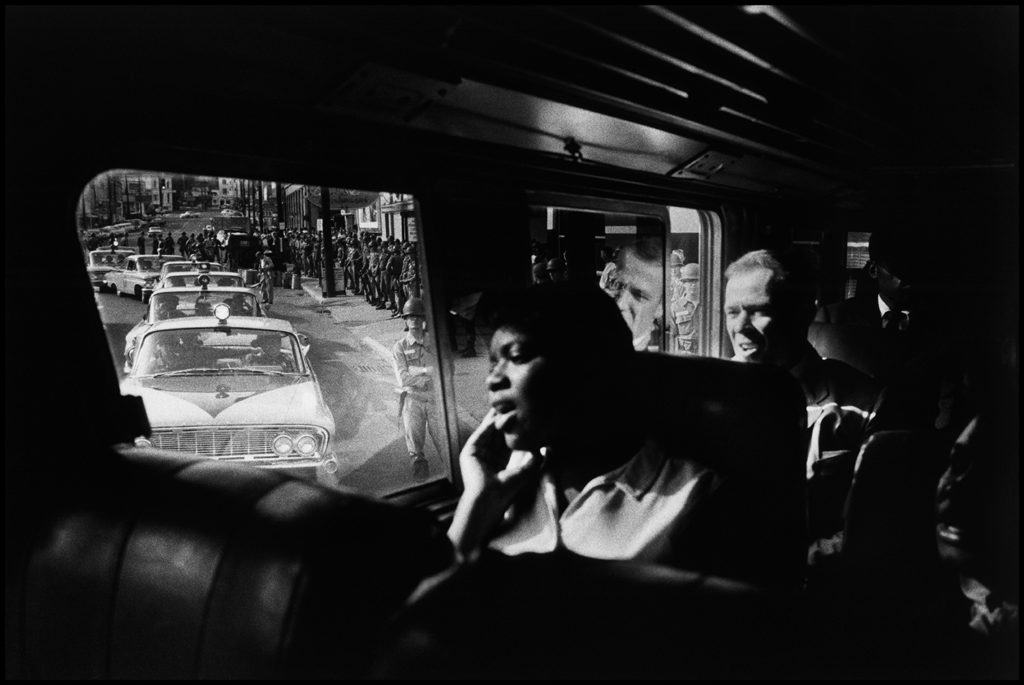

I do, but I don’t overdo it, because life goes on. In Time of Change, there is a picture of a woman in a shack holding a baby, made during the Selma march. I found that baby and I found the whole family recently and re–photographed them. Their lives had changed tremendously because of the Voting Rights Act that allowed the younger children to get a better education. One of the 11 children holds a master’s degree in library science and became head legal librarian at the State Capitol in Montgomery, Alabama. Almost all of the younger children I photographed have successful lives.

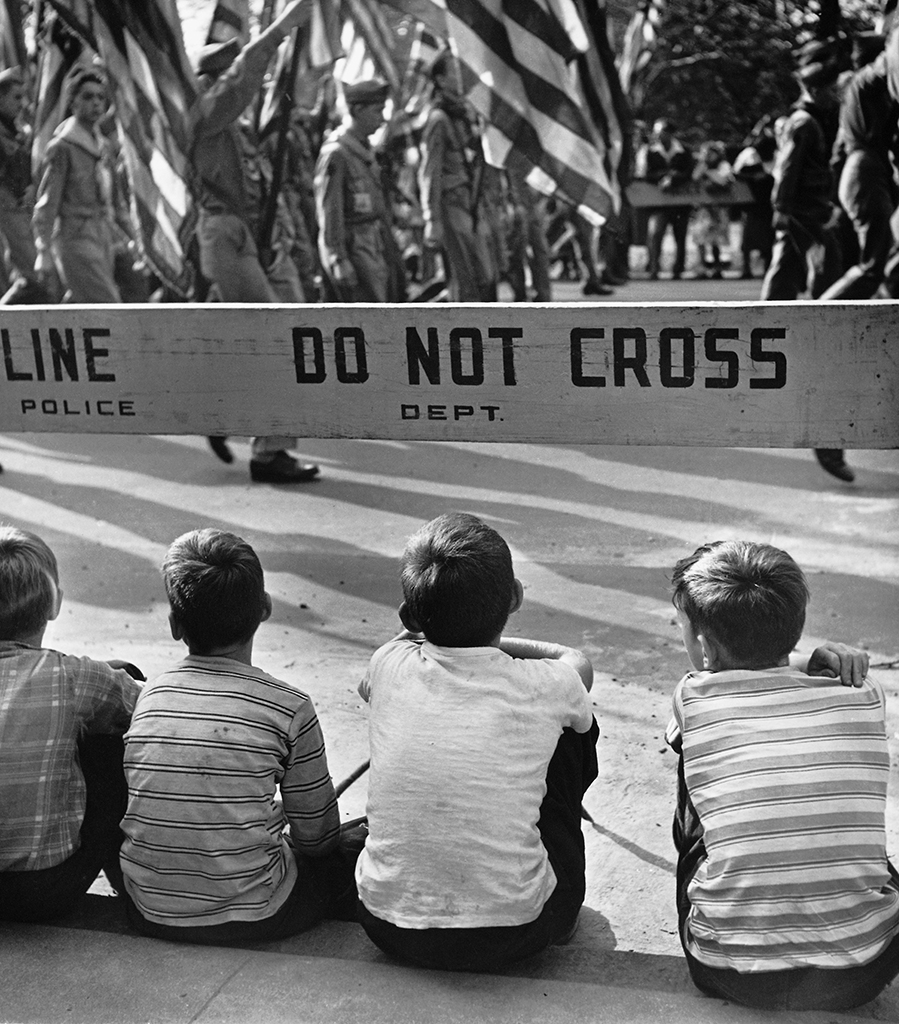

You photographed the Civil Rights Movement, primarily in the American South, from 1961 to 1965. In 1962 you received a Guggenheim Fellowship in support of this project, and in 1963 the Museum of Modern Art included these historic images, among others, in a solo exhibition. The book, Time of Change, Civil Rights Photographs 1961–1965 was published by St. Ann’s Press in 2002. In that same year, the International Center for Photography presented an exhibition of Time of Change. When you were photographing these events in the early ’60s, did you find it a frightening experience?

Oh, yes, because if you made a mistake and you got into a situation that you couldn’t get out of…that almost happened to me. I photographed a Ku Klux Klan meeting, but I drove my little Volkswagen bug too close to the cross. When they lit it, they said, “New York license plate so–and–so, you’re too close to the fire.” I knew that that was not going to be cool, to have New York license plates at a Klan meeting in Georgia. I stayed a while, took a few pictures, and then left.

Would you call the Civil Rights photographs a turning point in your life?

Well, it certainly made it possible for me to understand what I was getting into in East 100th St.. It was the prelude to East 100th St.. It was like my homework. I had borne witness to what was going on in the South and to some extent become sensitized to what was happening in the North, too. Without that background I don’t think I would have done East 100th St. the way I did.

What about your early fashion days? How did that happen?

The story I heard was that after Brooklyn Gang was published, Alex Lieberman, the creative director of Vogue Magazine, was having lunch with Cartier–Bresson. He asked Bresson if he thought the young Bruce Davidson could do fashion. Bresson’s answer was: “If he can do gangs, why can’t he do fashion? What’s the difference?” So I did a lot of fashion for about three years.

I rarely do fashion now. I came to a point in the Civil Rights Movement where I was doing fashion and also protest marches and I couldn’t equate the two things, so I gave up fashion. I’m good at fashion photography but it doesn’t give me meaning. It’s like cotton candy. It looks beautiful, but it melts in your mouth, and the sugar can rot your teeth.

During the early 1990s, you did an extensive series on Central Park here in New York, which culminated in the book Central Park, published by Aperture Press in 1995. How did that series come about?

I did a body of work for National Geographic Magazine called The Neighborhood, in which I retraced my boyhood steps in the Chicago area. After I completed that the editors asked me what else I would like to do. I said I’ll make a list of ten things. To make it an even ten, I added Central Park. We used to take the kids there and at that time it was like a dust bowl. You never knew when you were sitting with your children if there were hypodermic needles sticking them. Then the editors said, “Oh, Central Park, that’s a good idea.” I said, “I need four seasons and I need to be in black–and–white.” They said, “Oh, no, we are a color magazine. You have to do it in color and we can give you only three seasons.” So I went out and I started photographing Central Park. I exposed 500 rolls of film. Then we had a presentation. The next morning I got a call from the editor–in–chief Bill Graves, who said, “We’re pulling the plug on this project. Think of something else.” So I said to myself, “Good, I’m free at last,” and I went back to Central Park with my Canon Cameras and I spent the next three years photographing in black–and–white.

That series has been called a love poem to New York. Do you think of it that way?

Yes, the series I did was a love poem, but it was not a sweet poem. It had a fierceness to it. It had an edge to it, as I explored the layers of life.

What are you interested in photographing at present?

I’m interested in the balance of nature right now and the meaning of the vegetation that at times goes unnoticed in our lives. I just finished a large body of work called the Nature of Paris. It was shown at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris. The exhibition opened in June of 2007 and closed in September. In Paris I think I made an homage to vegetation. In that city the monuments take over. We go to the Eiffel Tower and we don’t realize there’s a 500–year–old tree growing right next to it. When you see the pictures it will be self–evident. I’m interested in raising people’s consciousness, my own included, to the meaning and the need for green space and vegetation.

When I began the project in Paris, I began by photographing some people in nature. For instance, my assistant found an elderly woman in the cemetery in Montmartre, a woman well into her 80s or 90s. There were cats standing on the tombstones, waiting for her to come to them with food. They wouldn’t just rush in. I photographed her and also lovers in the park and all that kind of stuff, and I was getting sick from it. I edited it all out, including the panoramas, even though the panoramas were successful, I thought. I edited all the 35mm pictures out. There was something I was doing with the square format that was coming through to me. In the end the whole show was nothing but the Hasselblad 2 ¼” photographs. I was able to disinvest all that other imagery, which I’d already done, into something that I hadn’t done, something that was new to me, fresh to me. And challenging.

I’m looking for another city that would be the extension of Central Park and Nature of Paris. I would like to continue the concept that was born through the Paris photographs.

At what point did you become interested in selling your photographic prints through galleries?

I was too busy photographing during the 1970s to become affiliated with a gallery. I became interested in the 1980s. It was Howard Greenberg who really brought me out of the fine art world “shadows” and into the sunshine. I had my first exhibition with his gallery in New York in 2002. I felt that Howard could really embrace my work and he did. Howard is, as they say in Yiddish, meshpokha, he’s family. He understands the work, he’s honest, he’s energetic, and he assigned me Nancy Lieberman, who is wonderful, and who manages my work for the gallery. Recently she arranged for my wife and me to go to Greece for a 75–print commemorative exhibition for the Hellenic–American Institute in Athens.

On the West Coast, Rose Shoshana and Laura Peterson of the Rose Gallery have mounted some of the most beautiful exhibitions I’ve ever had. They did a dye transfer color show of Subway that was amazing to see, and before that, Brooklyn Gang. They had a patron who underwrote the creation of a portfolio of Subway containing 47 very large dye transfer prints (20” x 24”) in an edition of 7. I think there are only two portfolios left.

I am now working with three people: Howard Greenberg Gallery, in New York, Rose Gallery in Santa Monica, California and the Sandra Berler Gallery in Chevy Chase, Maryland

After 9/11, did you have a desire to photograph events here in New York City?

Well, I went down a night or two to 9/11 to photograph. It was very difficult to get permission to work. I had sent a whole portfolio of photographs — not of 9/11 — to Hillary Clinton, but it never got to her. The FBI just X–rayed things and kept them, so I got those prints back a year later. So I didn’t have permission to get down there, but I knew someone who operated a building nearby and they were housing police overnight. He said the captain would be willing to take me around for a while at night, but that was all I could get.

In my slide presentation I have a photograph of the Twin Towers at night with the Statue of Liberty before 9/11. It’s a photograph that can be taken only with a 1700mm telephoto lens. There are only two in the world. I borrowed it from Canon. My wife did the scouting. She found a pier that jutted out a quarter of a mile into the bay. It’s a Kodachrome picture of the World Trade Center at night, lit by the office lights in the windows. When I took it I thought, oh, yeah, this is a perfect symbol of consumerism, materialism, all of that. But after 9/11 it became a memorial image, like two candles set on the altar of life and death.

Esquire Magazine gave me an assignment to photograph some aspect of America after 9/11. I just didn’t feel comfortable going someplace like the Grand Canyon, so I went to Katz’s Delicatessen. I spent a month at Katz’s making photographs of people eating pastrami, because I wrote, “Pastrami and Peace Go Together.” You feel very peaceful when you are digesting pastrami. I felt that freedom was about being able to photograph the impossible or the vulgar or whatever, or simply people enjoying themselves.

Did you feel the urge to photograph the people around Union Square who were looking for their relatives?

No. I felt there were so many photographers there that it would be well covered. I don’t like to photograph where there are a lot of photographers. It doesn’t feel right to me. I like to go where no one else has gone. Also, you have to understand my feelings. The whole thing knocked the wind out of my sails.

What projects are you involved with at present?

I still do some editorial photography. In fact, I just did a really interesting project with CareOregon, a private healthcare company that asked me to photograph a number of their members. These are people who are very, very sick. They are in their homes, not in the hospital. CareOregon made two beautiful exhibitions of the work, one at their headquarters in Portland and one in the Department of Human Services Building in Salem. Legislators got the chance to see people who really need care, and who are having good care right now through CareOregon. There were testimonials that were heart–wrenching.

Do you have any final statements to make about your work?

I would say I work out of a state of mind. When I’m photographing the dwarf in the circus, I’m confronting myself as a giant compared to this dwarf, but I’m not a giant compared to other people who might be a foot taller than I am. So then I confront another reality; I’m in another state of mind. Even in the Civil Rights Movement I’m erasing my own heritage and the town I grew up in. We didn’t have any social experience with black people at all. So I’m learning about that oppression as I go deeper into the Civil Rights Movement. And East 100th St. is another frame of mind. Then I work on that. I don’t read an article in The New York Times and think, well, that’s a good idea, I’ll work on that. No, my work is very personal. It’s a personal barometer of my life, a voyage of consciousness that is my life’s work. Each one is different. My wife says, “You always start with zero, you erase your clichés,” as I did in Paris. You’re only seeing what I ended with, what I felt the thing is. So there’s a psychological, there’s a visual, there’s a contemporary, there’s an artistic element.

I, personally, have been printing my body of work during January and February for the last two or three years, and I’ve accumulated about 1,200 prints in that time. I’m doing it because it needs to be done. One of my publishers, Gerhard Steidl, who does beautiful, highest–quality work, and who published England/Scotland 1960 in 2005 and Circus in 2007, is talking about publishing a four or five volume set of books of my life’s work. That would be great, if it happens.

I would also like to give my wife Emily credit for her keen intelligence, visual acuity and inspiration through all these years that we have lived and worked and raised our children together.

Jain Kelly was the assistant director of The Witkin Gallery in New York City from 1971-78. She has written numerous articles on various aspects of photography and is a fine-art photography consultant to collectors. Her email is [email protected]

Photographer Focus

Clemens Kalischer: The Invisible Man

Clemens Kalischer’s first look at New York in 1942 was out of focus. The malnourished German-Jewish refugee could barely make out the skyscrapers. Within five years he would be documenting everyday life in now classic images of the city. He chronicled the arrival of other displaced persons in New York harbor in the late ’40s. Kalischer’s first break came when, thanks to knowing French, he got a job counting words as a copy boy at Agence France Presse in New York. When their regular photographer was away, the editor asked Kalischer to cover the last voyage of the luxury liner Normandie, which had caught fire in New York harbor, and was being towed to New Jersey for dismantling. His reportage was cabled to Paris. Thus began his career as a freelance photographer.

Published

1 year agoon

December 22, 2021

By Brent Greggston

In 1948, Kalischer was invited by Beaumont Newhall of the Museum of Modern Art to be included in the exhibit “In and Out of Focus.” In 1955, Edward Steichen selected one of his photographs for “The Family of Man” exhibit. Since then Kalischer has exhibited all over the world. His work is represented in many international collections among which are: the Metropolitan Museum of Art; The Smithsonian Institute; The Brooklyn Museum; The Albertina Museum, Vienna; the Diaspora Museum, Tel Aviv; The Library of Congress; and the Photography Museum of Charleroi, Belgium, to name just a few. The career of Clemens Kalischer spans 60 years. He maintained a long relationship with the New York Times, working on assignment for over 35 years and doing freelance jobs for Newsweek, Time, Life, Coronet, Fortune and the Herald Tribune. Kalischer was 85 at the time of this interview, lived and worked in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. He ran the Image Gallery in Stockbridge for many years. The gallery showed work in all media, as well as the photography of artists such as Paul Caponigro, Eugene Richards and John Brook.

What was it like being raised in Germany between the two World Wars?

I remember my childhood better than I remember yesterday. I was born in Bavaria. When I was very young, we moved to the Harz Mountains. We lived at the edge of town next to huge woods, and I spent a lot of time running around those woods. At about the age of six, I had to go to school. We had a young woman teacher who had everyone line up by size, and I was one of the smaller ones. She had all of us bend forward, all the way down, then went around with a big stick and beat each one of us on our behinds. I came home to my parents crying. They were incensed and went to the school to demand an explanation. The teacher said that it was good for them and that they’ll know right away who’s in charge. I preferred playing in the woods! Around the age of nine, we moved to Berlin. When Hitler came to power in 1933, my father decided to leave for Paris.

Was there something specific that got you interested in photography at this time?

While a friend and I were going to purchase some oil paints at a department store, I came across a copy of the book Paris by André Kertéz. I had never heard of him but when I looked at the photographs I realized that he was seeing all the things the way I was seeing them on my very long walks. Several weeks later I bought the book—that book has remained with me all my life.

I understand you were in a French forced labor camp. Can you tell us something of that experience?

When the war broke out, I was camping with a friend in Brittany. We saw posters that read, “All aliens of German descent report to such-and-such a place.” Even though I no longer considered myself German, I decided I’d better go before they came to get me. I took the last bus and ran to the mobilization center where a French officer took my name and address. I asked for a telephone to call my parents and he said, “You cannot call anywhere, you are a prisoner. Go right in this room. You can’t leave any more.” It was a room full of people in shock, like me. We were shipped from camp to camp, and one night we were awakened by sirens and the order to leave at once. We marched for days on end without food, and were told not to sit down, or we would be shot. At a rare rest we threw away whatever we could. I could not give up the book, but I ripped out a few pages to lighten my load, it was that difficult. I was 19 or 20 years old. Before I was released, I went to eight different camps. The labor was strenuous, but I wasn’t going to give in, so I worked very hard. For three years I hardly ever ate any real food.

How were you able to escape?

We were saved unexpectedly by being on a list prepared by Varian Frey, a young journalist in France, with the help of Eleanor Roosevelt. We traveled on a tugboat from Marseilles to Casablanca to await a Portuguese ocean liner that took us to Baltimore, a trip that lasted six weeks. When we arrived I had my first real meal in three years, but was unable to digest it. When we arrived in New York, we were put up in a room for a little while. The temporary shelter in New York in which we lived would send me out to pick up food donations from stores. One day when I came home, I learned that our room had caught fire. I yelled out, “Where’s my book!” The firemen had thrown the burned rubble into the garbage cans in the street. So, I ran down and went through the cans and found my charred book.

Do you still have your André Kertész book today?

Yes, the burnt remnants of it, which are now in my attic. I haven’t seen it in a long time. I never tried to find out if I could get a newer copy.

Before the war you were training to be a painter. You arrived in America as a refugee with little or no experience in photography and no money. When you arrived in America, did you have any thoughts of becoming a photographer?

I had no thoughts about anything. I was extremely depressed and had lost all illusions. After three years in camps I weighed 90 pounds. The skyscrapers were a blur. The doctor said I needed more vitamins because I hadn’t eaten well for three years, and that my sight would come back—and it did. While working in the window department of Macy’s, I met a young photographer in the company print shop. He showed me photographs he took in the street. I was very impressed. He told me about some exhibits at the Photo League. On a day off, I searched to find it and, after seeing the work, I thought, “If I ever had a camera, that’s the kind of stuff I would photograph.” A sign on the wall announced a beginner’s class. The next day I signed up.

From this inauspicious beginning, how were able to establish a career in photography?

While I was working at Agence France Presse, word got around that I took photographs. One day, Mr. Rabache, the head of the Agency, called me in and asked me if I could do an assignment because their photographer was in the Midwest. I said yes, but I didn’t even own a camera. I borrowed a Rolleiflex from a French sailor I met in town. “You know how to use it?” he asked. I said yes, but I had no idea. I spent the rest of the night trying to get film into it. I got to the harbor at four in the morning. I spent the whole day on a tugboat following the luxury liner, Normandie, shooting without knowing . . . and it came out perfect. It was developed and went by the Atlantic cable to Paris. “Congratulations for a first-rate reportage,” came back from Paris, so I became a freelance photographer. The first magazine to publish my work was Common Ground and is where my “Displaced Persons” series first appeared. The editor encouraged me to come up with ideas like the nationality groups in New York, longshoremen, etc. I got paid very little and lived from roll to roll. One day, I said, “This can’t go on, I can’t survive.” I decided to do something different. I walked over to the New York Times and asked, “Who does one see about pictures.” I was sent upstairs. There I met a stern old lady. She said, “Sit down. What do you have?” She looked very slowly at my work. I was scared, thinking, “Does she really think I’m a photographer?” Finally she said, “Very good, come back in a few weeks with more.” She liked them as much the second time, but she had no use for them. She said, “Go down another floor and show your photographs to Grace Gluck in the book section.” Grace picked out periodically from whatever I photographed, that which symbolized something to do with a book. For many years I worked with Lonnie Schlein, photo editor of the Sunday Times “Arts & Leisure” section, and many more assignments followed.

Some of your most famous images are of refugees. You took them just five years after arriving in New York. When you looked through the camera lens, did you see yourself getting off the boat?

Yes, I totally identified with them. Therefore, they ignored me completely. Well, that has been my strength. When I photograph things, I become part of it, not a spectator or a curious journalist that intrudes. I wait until I feel that they are comfortable and have forgotten about me. I don’t ask permission because you can’t get real pictures by saying, “Can I take your picture now?” I sense when it’s okay. When it’s not okay, I stop or go away for a while.

Is that why you have been called “the invisible man?”

Someone in Belgium once asked me, “How do you do this?” and I didn’t know how to explain so I said, “I become invisible.” Very rarely do people even notice I’m around. Patience is also a big part of it. I wait for the moment when I know I’m no longer a novelty and then I make my best photographs.

You took a picture of Henri Cartier-Bresson on the New York waterfront while working on the “Displaced Persons” series, is that correct?

Yes. I discretely took his picture. A woman saw me take the photo and gave me her card. She worked for Harper’s Bazaar and wanted to see the photos, so I sent them to her. A few days later she called and said that Cartier-Bresson wanted to invite me to dinner. I was nervous because, like me, he was very quiet. At dinner we talked all the time, but never about photography. When I was invited to meet with him again in Paris just before his death, he looked at my new book. When it was time to leave he said, “Until next time.” But I thought there might not be a next time, so I replied, “Everything happens by chance.” And he replied, “Yes, yes, that’s right.” I met him at the beginning of my career and saw him again at his home in Paris at the end of his in June 2004.

I understand that you had a photograph in the famous “Family of Man” exhibit at the MoMA, the one that was curated by Edward Steichen. Coming into photography in the manner you have described, how did you manage this?

I was introduced to Steichen by John Morris. When I showed him my photos, he asked me to bring more. I brought him a box of prints. I didn’t hear from him again for a year or two, and then he called and said, “One of your pictures will be at the MoMA on exhibition.” At the time I wasn’t very involved in the New York photography scene and was surprised to be included.

Why did you move to New England after living in New York City for just nine years?

I never liked big cities. I needed space and nature. My best times in New York were the weekends I spent hiking with my friends in the country. One day I said a simple thing to myself, “I’m not going to stay my whole life in New York.” Most people would say, “Wait until you become successful.” I said, “No, do it now.” I got out a map of the United States and traveled with my eye and pencil. California for some reason didn’t pull me. The Midwest is supposed to be all flat, and I like mountains and trees. The South, probably not. Then I hit upon New England. I drove to Pittsfield and walked around. Towards the end of the day I met an old woman and told her I was looking to find a room or an apartment. It turned out I knew her son, a photographer. She said, “Between the trees, there’s a cottage and you can have it for free.” I was so excited. It was everything I wanted. For the first six months after moving there, all I photographed were trees.

After moving to New England you continued to support yourself with your photography. How were you able to do that living so far from New York City?

I arrived here with an old car and $75, and I didn’t know anybody. I thought, things will work out if I work and learn about the area. Not long after moving here I began working for Vermont Life. They do an essay on a village in the winter and many other topics. I also had small jobs in New York, and I would go once or twice a month to work there. That gradually diminished and in 1965, needing more space to store my photography, I moved into the former town office and opened the Image Gallery. It cost $14,000 to purchase the space, which was a lot of money for me back then.

You have done a lot of photographs for so-called alternative publications like The Sun, Jubilee, Orion, Common Ground, Yes, World Watch and Ploughshares. Why did you choose to work for them?

Well, that answer is simple. They use real photographs. They are more in line with what really interests me than most of the other publications. I’m interested in social, psychological and environmental questions. Photography has allowed me to learn and become involved in the things that matter to me. And what interests me are the things that give us hope, in spite of everything.

Throughout your career you’ve worked independently at your own risk and peril. Any regrets?

No. Sometimes it’s hard. But I’m free. I’ve never lost my taste for independence. Everything that has happened to me has happened by accident. Life has given me opportunities beyond my imagination and dreams.

On June 15, 2018, nearly 11 years after this interview was published in Focus, Kalischer passed away at 97 years old. His obituary can be found in the New York Times here: (https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/15/obituaries/clemens-kalischer-97-refugee-photographer-of-humanity-dies.html)

Brent Gregston is a writer living in Paris.

Happy Birthday, Berenice Abbott

New: Focus Magazine Returns To Print

GORDON PARKS: A CHOICE OF WEAPONS

Paris Photo 2021 Review

A Trillion Sunsets

Happy Birthday, Berenice Abbott

New: Focus Magazine Returns To Print

GORDON PARKS: A CHOICE OF WEAPONS

Arthur Tress: Finding Us In The Other

Dare To Go

What I Did Over Summer Vacation

Trending

-

Collector's Focus1 year ago

Collector's Focus1 year agoDare To Go

-

Collector's Focus1 year ago

Collector's Focus1 year agoWhat I Did Over Summer Vacation

-

Collector's Focus1 year ago

Collector's Focus1 year agoMagnum Photos

-

Vintage Focus1 year ago

Vintage Focus1 year agoBerenice Abbott

-

Collector's Focus1 year ago

Collector's Focus1 year agoSPEAKING OF TRENDS…

-

Collector's Focus1 year ago

Collector's Focus1 year agoGallery Trends

-

Vintage Focus2 years ago

Vintage Focus2 years agoFrederick H. Evans

-

Photographer Focus1 year ago

Photographer Focus1 year agoFascination With Beauty: Jock Sturges