Curator Interviews

John Szarkowski: Photographer, Teacher, Curator, Legend

For more than three decades John Szarkowski was the director of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. In 1961, he abandoned a successful photographic career that included several solo exhibits, two books, The Face of Minnesota and The Idea of Louis Sullivan, and two Guggenheim fellowships, to become arguably the most influential photography curator and theorist of all time. His classic Looking at Photographs: 100 Pictures from the Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, published in 1973, remains an important resource for both contemporary photographers and historians.

Published

2 years agoon

By

Kay Kenny

“Photography is the easiest thing in the world, if one is willing to accept pictures that are flaccid, limp, bland, banal, indiscriminately informative and pointless, but if one insists on a photograph that is both complex and vigorous, it is almost impossible.”

john szarkowski

During Szarkowski’s tenure at MoMA some of the now most prominent curators of our time were interns under his mentorship. Upon retiring in 1991, Szarkowski recalled his camera and began to photograph again—this time the familiar landscape of upstate New York. This work and his earlier photographs culminated in a retrospective exhibit organized by Sandra Phillips at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2005. The exhibit has traveled to major museums throughout the U.S., including MoMA, and recently ended its tour at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston in September 2006. Now in his 80s, he continues photographing and through his lectures and teaching, challenging the way we look at photographs.

When you succeeded Edward Steichen as the curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art it was 1962, you were a young man of 36 who had already received two Guggenheim fellowships, published two books, The Idea of Louis Sullivan, 1956 and The Face of Minnesota, 1958, and had several one-person exhibits of your work. Yet there is no record of you as an exhibition curator. How were you able to acquire the position at MoMA?

The people in charge at the Museum had all done exhibitions, so they knew that there is no special mystery to it, if one knew what to include and what to leave out. Then one must try to make meaning clear on the wall, which is an artistic and intellectual problem. It was perhaps felt that I had demonstrated some artistic and intellectual competence. The museum business was more adventurous and footloose in those days. It is true that a lot of the leading museums in this country were already directed by people who had studied with Paul Sachs at Harvard, but there was also room for people who had gotten their educations in irregular ways. The director of the Museum of Modern Art when I went there was Rene d’Harnoncourt, who I think had a degree in bitumen engineering, but whose artistic education had begun before he learned to crawl. Many people who had played extremely important roles in the museum’s program had not been officially approved for museum work, e.g., Jim Soby, James Johnson Sweeney and Steichen—to restrict myself only to those whose names begin with S. Among colleagues of my own time at the museum, Monroe Wheeler, Arthur Drexler and Dick Oldenburg, among others, were educated in ways that might now seem slightly exotic for one hoping to enter museum work. But that was all long ago. Certainly I would never be asked to do that job today, when there are PhDs in the history of photography on every street corner.

You described to Mark Haworth Booth (History of Photography, Vol. 15, 1991) your job interview with Steichen and Alfred Barr as several moments of silence followed by Steichen saying, “‘Well, Alfred, It’s a gamble’ and Alfred smiled and we all shook hands.” In your three decades at the MoMA you’ve spawned a great number of photographic curators who now run museum departments of their own, and you’ve launched many a photographer’s career, notably the fabulous four: Arbus, Winogrand, Friedlander and Eggleston. Do you think your approach to photography, both in hiring potential curators and discovering photographers, owes something to Steichen’s faith in you?

Faith is perhaps not quite the right word. Steichen had many virtues, one of which was that he was a realist, even though he could do a pretty good romantic. He thought, I think, that I was a good bet for the job, or at least the best of the visible lot of candidates. If I had proved him wrong, I trust he would have done the manly thing and tried to persuade the museum to get rid of me and try again.

You were an ardent and obviously accomplished photographer before you went to the University of Wisconsin where you majored in art history. You once referenced working for a local photo studio during that time. Besides discovering the great masters of painting, was that when you discovered the photographs of Ansel Adams and Walker Evans? They seem to have had a profound influence on your own approach to image making.

When I went to Madison at 17, I showed a portfolio to the portrait photographer Frederica Cutcheon, and she hired me on the spot at the truly princely sum, for part-time student help, of 75 cents an hour. I think she hired me because I knew something about the photographic gray scale and had a sense of how to fill the sheet. Certainly she did not hire me for my sophistication, which would have been of no use to her and very possibly a handicap to me. Most of what I liked came from U.S. Camera Annual which was quite a good book and Coronet magazine, which favored photographers from the old Austro-Hungarian Empire, ranging from Brassaï and Kertész to conventional pictorialists—people fond of back-lit swans, sailboats in the fog, etc. It was some months later—perhaps the next year—before an art history professor named John Fabian Kienitz told me to stop interrupting and go to the co-op and buy a book, the name of which he wrote on a file card. I dutifully bought the book, which turned out to be American Photographs, by Walker Evans. It mystified me completely, except for the lady in the striped blouse standing in the door of the barbershop, which I could see had some design quality. However since I had paid four dollars for it, I felt obligated to keep looking at it to get my money’s worth, and gradually it improved. Sixty-odd years later it is still improving.

You were known as a “formalist” in your theories about photography. Some have defined this as the relationship of elements within a frame: the shape of the shadows, the depth of tonality, the lines of the planes. These elements define the form, and it is form that defines the content. Is this a description of how you evaluate meaning in photography?

I think many people have a very shaky sense of what artists mean when they talk about form. It has nothing to do with cubes or planes in space or organic looking shapes like those in late Kandinsky; in fact it has little obvious connection with design, as that word is usually used. Rather, it has to do with the relationship between content and container. Think of photography as a kind of container, not like a pail, for example; one cannot carry water in it, but it will hold other kinds of content, and those that it accepts most efficiently and most gracefully are gratefully pursued by photographers who would rather work with their medium than against it. On occasion a photographer of talent—consider F. Holland Day—will decide, for example, to photograph the Crucifixion, which seems to me a project doomed to failure because to stage it persuasively, one would have to break too many serious laws. Frank Lloyd Wright said a very good thing about form: he said that Louis Sullivan came close when he said that form follows function [content], but that in fact they were the same thing. Certainly one cannot change one without changing the other. Or one might say that content is the disembodied idea, the soul, and that form is the physical body, but we know nothing of the idea except what is expressed in the body. Mallarme also said a good thing on this, to Degas, after Degas said that he had some very good ideas for poems, but the poems were never very good. Mallarme said, “But Edgar, that is because one does not make poems out of ideas; one makes them out of words.” I once had a student in the history of photography who asked me, I think more in sorrow than in anger, if it was really true that I was a formalist? I said, “Isn’t everybody?” but I don’t think she was satisfied. But I believe that all good artists are formalists, if the word means anything at all. Only bad illustrators could think that an idea exists prior to its formulation.

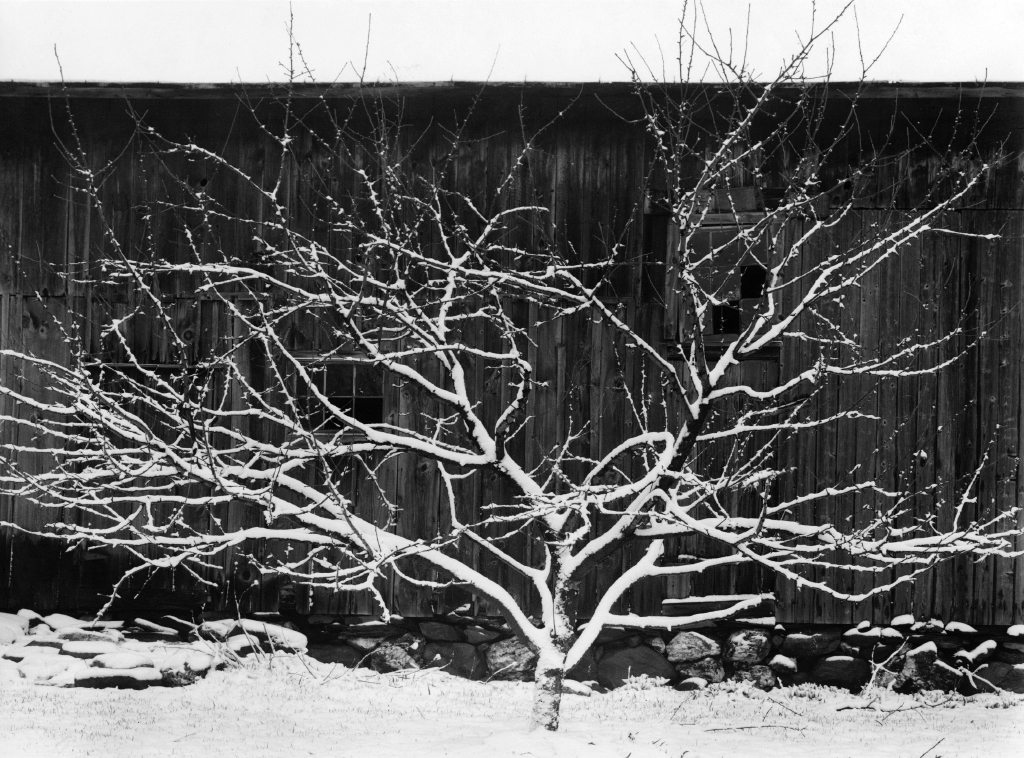

You bought your apple farm in 1969 in upstate New York. Now you seem to spend all your time photographing the apples and the land around you. You’ve often been heard to use the apple tree as a metaphor for photography as art when giving talks at museums and universities. It is hard to look at your photographs of your farm without recognizing the reverence you feel for it. Do you believe that you’ve honed your capacity to embody this sentiment into your photography through the study of formalist structure, or do you think this is the intrinsic “equivalent” that Minor White once referenced in an issue of Aperture in an article on looking at photography that described the four kinds of photography: documentary, pictorial, informational and the equivalent?

Our place was never an apple farm. When it was a farm it was a typical 19th-century subsistence farm, run with one team of horses and an amount of hard work that I prefer not even to contemplate. I manage to keep the meadows open and try with indifferent success to keep up with ten apple trees that I have put in, and I do a little grafting on them from old local trees, mostly seedlings, but I am certainly not arrogant enough to think of myself as a farmer. It is true that I love this place, and it is a good subject for me to photograph because I now know it fairly well, and thus know when I have failed to make a photograph that is good enough for the subject, which is of course most of the time. I don’t like to argue with Stieglitz, but the term equivalent has always made me a little uncomfortable. It seems to suggest that the same thing can be said in two different ways, which I doubt; it also suggests that the possible meaning of a photograph is potentially larger or nobler if it can be translated into philosophical or psychological language. As for Minor’s attempt to explain photography by dividing its practitioners into four classes—from peons to priests, more or less—I’m afraid this is merely silly and represents White at his least interesting and least useful.

You recently wrote a book on Ansel Adams to accompany the exhibit “Ansel Adams at 100.” In an interview regarding Adams, you stated that “ . . . it has been impossible for a photographer to deal with the issue of landscape—an issue that has always been important for me—without somehow confronting Adams.” Before you accepted the position at MoMA, you had just embarked on a project examining the wilderness area in Northern Minnesota and Canada, funded by your second Guggenheim. Clearly, the landscape and its use have always been profoundly important to you. Do you see Adams’ influence and a continuity of your approach to land use in your new work on the farm?

I believe that Adams’ passionate dedication to the western landscape—the only subject, I think, about which he deeply cared—was his expression of an intense spiritual need to somehow become part of—to join himself to—a world that was to him sublime. He pursued this grand ambition with workmanlike humility, applying his system to his experience and in his best years making pictures of fierce and original intensity. Neither the grand ambition nor the humility comes easily to us today; we favor—certainly I favor—a less vulnerable posture toward the world. But the high virtue of Adams’ finest work is nevertheless available for our instruction and inspiration.

You stopped making photographs, at least for the public eye, during your tenure at MoMA. Yet you seem to have taken up your camera again and with apparent ease slipped into the stream of your earlier images. Now you have a gallery, Pace/MacGill, and a retrospective of your earlier and current work traveling to several major museums, including MoMA. In the catalogue for the exhibit, you published some of your letters to friends and family. In one there is a quote: “When I was 20, I gave myself 10 years to continue my education; now I want just 10 more and promise myself that from the age of 40, I will not learn a single new thing of my own free will, but will begin to cast it forth again, in a slightly changed form. I come from a long-lived stock and expect at least 40 years after (the age of) 40 to practice that which my education will have presumably taught me.” (March 1955). Do you think that your recent work is the fruit of this foresight?

Photography is the easiest thing in the world, if one is willing to accept pictures that are flaccid, limp, bland, banal, indiscriminately informative and pointless, but if one insists on a photograph that is both complex and vigorous, it is almost impossible. One can, like an unreformed gambler, keep going out, keep trying, hoping that one might one more time be visited by luck or grace and make one more photograph that is exactly right. I did not photograph much or very well during the 29 years that I was at the Museum because I had a job that required my best attention; and if one is to photograph seriously, that also takes one’s best, concentrated attention. It cannot be picked up on Friday night and put away on Sunday—except perhaps by the greatest geniuses or talented beginners. The quote from the letter is obviously an evasion, if not an outright lie; it is like the promise of the drinker who says that for one more drink tonight he will swear off in the morning. But my intention was clear. I meant that I wanted to be a useful and responsible citizen, but please, not quite yet.

There is a sense of walking back in time when viewing your retrospective. That may be partly because so many of the images are from an earlier time before you became Chief Photography Curator at MoMA. However the prints are small, by today’s standards and black-and-white. Even the newest work has a look of vintage prints to a contemporary eye. As you photographed these images and prepared for your retrospective, what thoughts did you have on the overall concept of the show? Was this a formal decision to connect the earlier work so strongly with the later work?

In principle a retrospective exhibition or book is a very simple thing. It is a report on an investigation of what a given artist has made so far that might still deserve consideration. Sandra Phillips and I chose the show together, and our judgments were very, very close. I think there might have been a little horse-trading in the case of three or four pictures, but basically we had the same view as to what should be included. If some larger meaning seems to emerge from that choice, that is a byproduct of the process. I mean that in the case of a retrospective view, one must not decide on the plot first and then illustrate it; one must allow the work itself to determine whether the artist is a fox or a hedgehog. I work in black-and-white because to me it seems less fearfully constricting than color, which seems instantly to rule out—for photographic purposes—so much of what I like to look at. Size is a very interesting problem and deserves a thick book. Big is not bad; consider the pyramids and the elephants. Furthermore, I will say without equivocation that the first pictures that Talbot made with cameras were too small. They were a little smaller than 35 mm contacts, and his wife called his cameras mousetraps. It is hard to do serious work while one’s wife is making jokes about how one goes about it.

On the other hand, I think it would not be unfair to ask the Germans exactly what they think they are achieving by making photographs that seem to compete—at least in size—with Raphael during his Roman years. To my mind something is lost in these gigantic prints. What is lost has to do in part with the fact that photographic materials—especially color materials—are not intrinsically beautiful—not like marble, or tapestry, or bronze, or paint on canvas. They look instead like something manufactured out of petroleum and soybeans in factories that cause serious pollution problems. The traditional solution to this problem has been to make the print—the object itself—invisible. Classic photographic technique is designed to encourage the viewer to look not at the print but through it, and to believe that they are seeing a space with grass or flesh or bricks in it. But this deceit becomes increasingly difficult, as the print gets bigger. A little piece of black, half the size of a fingernail, can be read as a dark place, but if it is made the size of a dinner plate it becomes merely a big piece of black, signifying nothing, and one finds oneself looking at the surface—at the not very seductive physical object. It is also obvious that the size of the print implies the size of the audience. A photograph by Harry Callahan implies an audience of one—one person at a time—who, under the best circumstances, is sitting down and holding the picture in his hands. One can also exhibit Callahan on a museum wall, but it is difficult to get it seen by an audience in the mega-thousands.

An interesting test case might be the pictures made in 2004 by Thomas Struth of the visitors viewing Michelangelo’s David at the Accademia Gallery. It seems to me that these pictures are of interest from a documentary point of view. To be able to study closely, without rudeness, the postures and costumes of a contemporary museum audience is certainly fascinating. However it is not clear that this information need be conveyed in prints that are 10 feet long. The size surely implies that some larger meaning is involved here, some public issue that requires the declamatory rhetoric of mural scale. Many years ago Ray Metzker and the Bechers found an interesting approach to this problem, by making pictures that changed their content as one approached them more closely. In any case the issue of rhetorical wall pictures does not seem important to my own work, at least not at the moment. My work today certainly does not seem to me retrospective. I am not interested in repeating problems that I have solved in the past. I try to make photographs that describe, and I hope at their best embody, what I find most interesting in my life now. I am not much interested in what the market thinks, or what most critics think, but I certainly do not begrudge them their theories and preferences. I think I work now to demonstrate to myself that my own sense of the world is true.

You once said that as an artist, you have an early period and a late period but no middle period? Is that next?

As you doubtless know, Duchamp said that a story should have a beginning, a middle and an end—not necessarily in that order. Perhaps I might work for a while longer on my late period, before rushing off to the middle one.

“John Szarkowski: Photographs” is accompanied by a fully illustrated book of the same title, published by Bulfinch Press. The 156-page hardcover volume features an introductory essay by Sandra S. Phillips, SFMoMA’s senior curator of photography, a chronology, amusing and revealing excerpts from Szarkowski’s personal correspondence and 84 tritone photographs.

Kay Kenny is a photographer, writer and a teachesr of photography. www.kaykenny.com

You may like

The Corcoran Gallery of Art occupies an unusual place in the federally funded landscape of Washington DC museums and galleries. Surviving as it does: a long-established private institution bobbing up and down through waves of controversy, applause and economic crisis, it is a school and a museum and probably closer to the heart of the Washington-area art scene than it’s heavily endowed neighbors. Now under new leadership, it is poised for change. Paul Roth, the Corcoran Gallery of Art’s Curator of Photography and Media Arts, is ready for the challenge: his areas of expertise are postwar American photography and the history of film. Politics and art fascinate him. Looking at images: anxiety and discomfort provoke him. The Corcoran, with its privately funded flexibility in this government town seems like the ideal place for this curator.

Your background is a degree in Art History at the University of Arizona in Tucson. Was curating art always a goal?

I first wanted to be a photographer. I was lucky enough to grow up in Tucson, where one of the best high school programs for photography is located at Tucson High School, and I trained there and thought I would become a photojournalist. When I was 18 I looked for work at the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona, a place I had visited since I was 14, and I was hired to catalog the Edward Weston Project Print Collection. This was an amazing leap on their part, to hire a teenager to do something like that, and it changed my life. I decided to become a curator while working there during the next five years. I’m not sure what lead directly to that decision; I was there because I loved the medium and liked being around pictures. It consumed me. I was able to do many things and had access to their great collections of photography and archival materials, and in time it just seemed obvious that my career would be in curating.

You’ve been with the Corcoran Gallery of Art for over 11 years. Were you a photography intern at another museum prior to that? When did your fascination with postwar American photography grow into a passion?

I’ve worked at three museums. From the Center for Creative Photography I went to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, where I worked for Sarah Greenough as the archivist for the Robert Frank Collection and served as the assistant for the retrospective Robert Frank: Moving Out. After Moving Out was completed I was hired at the Corcoran by one of that exhibition’s curators, Philip Brookman. Between the National Gallery and the Corcoran I worked briefly at the Library of Congress and the Washington Project for the Arts on specific projects. I’ve had incredible luck in that I’ve always worked for great people and had fascinating jobs with great collections. “Learning from the experience” has become the meaning of my life.

The amazing access I had to the work of Robert Frank is what drove me to specialize in post-war American photography. It’s unfashionable to use the word “genius” these days (and he probably doesn’t like hearing this) but Robert really is one. For 4 ½ years I was able to work every day with his work prints, proof sheets and negatives, and to think exclusively about his photography and his books. I began to think of American photo history as it led to him and grew out of his influence. Ultimately my understanding of art, politics and life was affected by his visual legacy.

In addition to your work as a curator, you also teach the history of film and you have organized a number of film series for the National Gallery including “The Films of Gordon Parks,” a photographer who donated 227 of his works to the Corcoran, following an exhibition of his work. Now that we have entered the digital age and high quality DVDs are readily available, do you see more still photographers creating narrative film-like presentations and more collectors turning to film and video as collectible?

A couple years ago I saw a multimedia narrative presentation of still and moving images by an artist while judging work for a grant-making organization. It was an amazing packaging of disparate documentary works on a single subject. Unfortunately I have seen nothing like it since. Some individuals are collecting media arts in digital form, though very few have offered such works as gifts to the Corcoran. I’m not sure whether the number has increased dramatically in recent years, though certainly more artists are making work for presentation on DVD, whether in installations or as projected pieces. The collectors I know of who acquire lots of projected media works are the bravest ones, the ones collecting on the cutting edge, the ones least concerned with displaying the object quality of their acquisitions.

The Corcoran Gallery of Art is rooted in Washington DC’s history. As a privately funded museum in 1869, it was founded “for the purpose of encouraging American Genius.” William Wilson Corcoran, the philanthropist whose collection of American Art was the basis of the museum, is reputed to have bought work only from artists with well-established reputations. Today the Corcoran stands in the shadow of much larger government-funded Washington museums. Competition is fierce and photographs from well-established artists have reached the same stratospheric heights as painting and sculpture. Does the Corcoran still adhere to its founder’s dictum of collecting only blue-chip art?

“Blue-chip art” can be interpreted a number of ways: while it seems to generically refer to work of a high quality, it also implies a high prospective investment value, or work by “name” artists, in the sense of “blue chip stocks.” And in that sense we do not acquire only blue chip work, because to do so would violate the very nature of photography, which in my view is a democratic medium. We acquire documentary and vernacular work as well as fine art photography, and we acquire work by younger and lesser-known artists as well as established figures. Both in photography and in contemporary art, collecting means taking risks, and much of the best work in our collection has come because we have tried to remain open-minded and take chances. Having said that, we are currently re-focusing our energies to plug certain gaps in our holdings, and that will mean targeting specific artists and particular works.

We do have many great collections of photography in Washington, some of them vast and encyclopedic in scope, such as those at the Library of Congress, the National Archives and the various museums of the Smithsonian. Because they are here, we do not need to duplicate what they do. And we couldn’t, even if we wanted to. So we try to build our collection and make it better than before.

Considering that photography was in its infancy when William Wilson Corcoran bequeathed his collection to the museum, how did the photographic collection begin at the Corcoran? Was there a major donor who began it with a similar passionate interest in American Photography? According to David Levy, director of Corcoran Gallery for many years prior to resigning in 2005, photography collecting was pioneered by the Museum of Modern Art, the George Eastman House and the Corcoran. Who were those pioneers at the Corcoran?

While the Corcoran is an important part of the story of the institutional recognition of photography as art, we are not pioneers in the sense that MoMA or the Eastman House are. But we did begin accepting photography into the collection in the 19th century, and we began exhibiting photography during the Pictorialist era. William Wilson Corcoran himself is likely the person who brought the first photographs into the collection. But the real “pioneers” of photography at the Corcoran were the people who made the medium an active part of the museum’s program in the late 1960s and into the 1970s and 1980s: Walter Hopps, Jane Livingston and Frances Fralin. They all did groundbreaking work during their respective tenures at the museum.

The Corcoran also is well known for its School of Art and Design (now College of Art + Design) founded in 1890. Is it a common practice for alumni to contribute to the Corcoran’s photography collection?

The collection does include the work of Corcoran alumni and faculty members. From the 1970s on, the museum has been an important force in the local practice of photography, and it was a natural step to reflect that in our collection. We still do so, though we are particularly cognizant of the potential for conflicts of interest. But to give a recent example, last year we acquired works by Joyce Tenneson that were made during the early 1980s when she worked in Washington.

The Corcoran appears to be undergoing a major shift in direction since 2006 when Paul Greenhalgh was appointed as director and president of the Corcoran. The long touted new addition by architect Frank Gehry has been sidelined, exhibition schedules have been dramatically altered, and there is talk of a return to generating exhibitions from the Corcoran curatorial staff rather than relying on exhibitions organized by other institutions. However, the current exhibitions Ansel Adams and Annie Leibovitz: A Photographer’s Life, 1990–2005, both through January 2008, were both organized by other museums. What plans does your department have for fulfilling this new directive?

The Corcoran has and will continue to host interesting traveling exhibitions, just as we organize our own exhibitions and send them out on the road. Both Ansel Adams and Annie Leibovitz: A Photographer’s Life, 1990–2005 are examples of shows organized elsewhere that we thought our audiences would want to see. But we’ve been making our own major exhibitions all along and will continue to do so. Under Paul Greenhalgh’s leadership we are changing the way we make major exhibitions, but I don’t think we are planning to ignore other museum’s exhibitions. We are still always looking to see what is out there that fits well with our program, and we are well aware that we can’t organize every type of show our audience wants to see.

We are planning several major exhibitions that involve photography. Right now I am organizing Richard Avedon: Portraits of Power, a survey of Avedon’s portraiture that deals with politics and power. The work included spans his career and the show will be timed to the American presidential election season, opening just after the conventions in Fall 2008 and running through the end of the inaugural in January 2009. Philip Brookman, who is now our Director of Curatorial Affairs, is organizing an Eadweard Muybridge retrospective for 2010. And a team of our curators is working on a sweeping survey of Postmodernism for 2011, which will include many photography and new media works.

Where will you turn to for these new curatorial initiatives? What feeds your curatorial imagination?

I’m really interested in the intersection between photography and politics, and in the ways that photographers use the medium to reflect the social world. I’m not sure if I developed this interest from being in Washington, or if I came here because this was the perfect place to view the medium through this filter. Working on the Robert Frank archive at the National Gallery, in a building near the U.S. Capitol, was certainly an influence. Seeing how artists think when installing their work in the Corcoran, which is a few hundred feet from the White House, has been an ongoing revelation. Context is so important: we always think about how images reflect the country — and its people, its promise and problems — when considering our exhibitions.

You are a photographer as well as a curator. Your work was included in the Crosscurrents series at the University of Maryland in the 2004 “Room Full of Mirrors.” The 14 artists in the exhibit were described as ‘using the collage aesthetic; incorporating various methods using chance and accident to allow creativity to work through them not from them.’ You have also been involved in a grass roots organization of Washington area artists WPA\C that until recently was part of the Corcoran Museum. You have juried exhibits for many organizations. Clearly, you have a pulse on the kind of work being generated by contemporary and as yet unheralded photographers. What trends do you see there?

Well, interestingly, I don’t feel all that “in touch” right now! I’ve been buried under the work I’m doing on the big shows we have scheduled. But when I do have time to look at new work, I’m really interested in how photographers are evolving their representation of capitalism and its discontents. Gursky’s rational re-orderings of the middle class world of consumption and power are giving way to more explicitly political visions like Chris Jordan. I’m also seeing more work I like that seems suffused with a blanket of anxiety, like that of Amy Stein, Noelle Ta, and Kate MacDonnell, all of whom have roots here in D.C. And I am interested in the ongoing return to earlier photographic processes in the face of the medium’s eclipse at the dawn of digital.

You were also part of a panel discussion, “The Artist’s Responsibility in a Political Environment” that reflected on the role of the artist as a political pundit and activist. Documentary photography has a long established place in political activism but what about the new photography where lines are blurred between the real and the created?

Well, that’s an interesting question. I have to say that I think most fictional, performative and theatrical work is really boring. It is, I think, the most overrated avenue of photography I can think of. Most of the work I see shows just how hard it is to make a single image out of set design and stage direction — usually the work people praise is incredibly awkward, emotionally empty and totally unrevealing. I am kind of fascinated by own negative response, though, and I want to investigate this work more so I can see why I reject so much of the work I see. I recently got Lori Pauli’s exhibition catalog from her show at the National Gallery of Canada, Acting The Part (Merrell, 2006) so I can learn more about it. Maybe it will temper my attitude.

The Corcoran’s Director Paul Greenhalgh was quoted in a Washington Times interview as saying: “This institution should be a think tank. We’re not in the business of pleasing people; we should also challenge and educate.” With that in mind: what would be your ideal exhibition?

My ideal exhibition is a survey of the medium through the notion of the uncanny, first defined by Freud as the state where something is both familiar and foreign at the same time, resulting in profound discomfort and anxiety. This show would look at photography’s history as a vehicle for exploring what lies beneath the visible: the uncomfortable truth below the pleasing, understood and well-ordered surface. My favorite photographs are the ones that destabilize our consciousness rather than confirm what we think we know.

Any plans for that in the future?

Well, fortunately yes! That show is tentatively scheduled at the Corcoran for 2011–12. If all goes well it will be the next big show I work on after Richard Avedon: Portraits of Power.

The Corcoran Gallery of Art is located at New York Avenue and 17th Street, NW, Washington, DC. Please see the Gallery’s website for hours and admission fees.

Curator Interviews

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Photography Curator Sandra Phillips

Published

1 year agoon

December 25, 2021By

Kay Kenny

Sandra Phillips is Senior Curator of Photography at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, an institution that has dynamically supported and collected photography since its opening in 1935. Phillips received a B.A. in art and art history from Bard College in 1967 and an M.A. from Bryn Mawr College in 1969. She earned a Ph.D. in art history in 1985 from City University of New York, where she specialized in the history of photography and American and European art from 1849 to 1940. Phillips has written and lectured widely on photography and is the author or co-author of several books and catalogues. Her recent exhibitions include: “John Szarkowski: Photographs”; “Diane Arbus Revelation”; “Police Pictures: The Photograph as Evidence”; and “Shomei Tomatsu: Skin of a Nation.” Despite the globalization of media and the arts, regional differences are a curious reminder that a sense of place still informs our imagery. Sandra Phillips has an unusual vantage point having grown up with the New York’s MoMA and overseeing the photography collection at SFMOMA.

All of your university degrees, including your Ph.D. from the City of New York, are in art and art history where you specialized in the history of photography along with American and European art from 1849 to 1940. Did you have a primary mentor for the study of photography’s history at that time?

No, but I grew up in New York and loved museums, and I consider myself a student of the work shown at the MoMA. In fact, I remember seeing the show, “New Documents.” I remember seeing the Arbus pictures because I went with a friend, and she thought it would be fun to go. I remember seeing a man spit at some of the pictures in the show.

When did you gravitate towards photography as a field of study?

I come from a family of art people -my dad was an architect, my mom a landscape architect, and I thought I would be a painter, so when I went to school, that’s what I studied. But I became more interested in looking at art, and it seemed really interesting that no one was then taking the history of modern American art really seriously -this was in the 60s. And then when I got more involved in modern American art, it seemed that one of the major contributions was in photography, which was even less studied, and that intrigued me even more.

Under the direction of curator John Humphrey, SFMOMA was one of the first museums to recognize photography as an art form, over 70 years ago. Can you tell us what initiated that recognition and began the process of creating the SFMOMA’s photography collection in 1935, the same year that it opened? Was there a special collection donated to the museum at that time?

The San Francisco Museum of Art, as it was then called, was founded by a group of wealthy local individuals. You realize that San Francisco became a city very suddenly when gold was discovered, so everyone in the world was interested in San Francisco, and the 49ers were here and many of them used the services of the daguerreotypists to send records of their recent fortunes back home. There has been a very strong interest in photography here since the 19th century–remember Carleton Watkins, Muybridge, and others used this as their base. There has never been a tradition of important art created here -that is relatively new, but when the museum was founded in the 30s there was an impressive range of important photographers he could own or lease. This might include tents, caves, pictures made within buildings, etc. He is still an active collector, and I tease him that we’re planning the Return of the Paul and Prentice Sack Collection.

SFMOMA recently received another significant donation from the Emil & Silverstein Collection. What distinguishes this collection from the Sack collection?

This is a very different collection. I would describe the pictures as psychologically informed. It is historical, but the emphasis is on work of surrealist inflection produced in the 1930s and the present. The pictures are also in their own way very personally meaningful to their owners, in a very different way from

the work in the Sack collection.

SFMOMA prides itself as having from the first, viewed photography as a modernist art form. Its collection of over 15,000 prints is known for it’s early American and European modernist photographers as well as Western American Landscape photography. How does modernist photography differ from contemporary photography? Would you define photography in the same terms today as in the days of your predecessor, Van Deren Coke, who established the department of photography in 1980?

I would define modernist photography as photographs which aspire to modern art, and which were made by Americans and Europeans in the 1920s and 30s, essentially. Since I came to the museum, in 1987, I have enlarged the scope to include 19th century and have emphasized our tradition of landscape representation. Coke thought about photography in terms of modernist art -I believe the concerns of contemporary photographers are related but different.

In 1980 the exhibit “California Photography 1945-1980” examined the aesthetic and history of photographic image-making unique to California. Do you think there remains a special sensibility that divides West Coast from East Coast photography?

First, I had nothing to do with the California show, but yes, I would generally say that in the west there is an abiding interest in land use and land issues, which is not generally shared by photographers or audiences for photography in the east.

In California today, what influences define West Coast photography?

There is more of an understanding of Asia here.

Before coming to SFMOMA in 1987, you were the curator at Vassar Art Gallery in Poughkeepsie, New York. Did your experience at Vassar provide you with a heightened sensitivity to women photographers?

Not really, I was there for about a year. But in general, photography has provided women with opportunities not so obvious or available in other fields.

You have organized exhibits and written numerous essays on women photographers, most notable Dorothea Lange in 1994 and Helen Levitt in 1991. Your essay “Women Artists in California & Their Engagement in photography” appeared in the book Art/Women/California 1950-2000. What special concerns faced women photographers in the past, and do you believe that many of those photographers may still be undervalued?

If you mean monetarily undervalued, I suppose you could say that, but this is an aspect of the field that really doesn’t interest me too much. The “concerns” that women faced in the past are ones they -we -face today. If we are mothers who need to work, how do we do this? That is probably the most obvious difference.

There is an interesting story about one of Dorothea Lange’s most famous photos, a migrant farm worker named Florence Thompson. As Lange’s photo gained wider recognition and value, Florence and her children came forward, angry that neither monetary compensation nor a copy of the photo were ever given to them. You recently organized the Diane Arbus exhibit, another controversial photographer often accused of exploiting her subjects. How do you address this issue when the subject comes up?

Well Lange worked for the government, she had a job, and her photographs were made to serve a purpose, one that she very much believed in; then the times changed. I do not think she would have said she was exploiting her subjects. And frankly I don’t feel comfortable with the idea that Arbus “exploited” her subjects either, they look very interested in her, as much as she in them. When she was making these images, they were very new, very raw material. I don’t think you would see anyone today spitting on her photograph of a young man in curlers, as I saw in the MoMA exhibit “New Documents.” I think we’ve become more tolerant, as a culture.

Documentary photographers, such as Dorothea Lange, never anticipated their work on a museum or gallery wall. Their photographs told a story meant for the printed page of national magazines. It seems that today’s documentary photographers anticipate a museum or gallery exhibit along with a well-designed coffee table book. Do you think that the nature of documentary photography has changed to appeal to a more limited audience?

Photography has changed technologically, and the ambition of certain photographers has changed, I think that is the way I would put it. Someone wise once said that the process gets easier but the number of important photographs remains the same. There is a lot of indifferent work being made, but some very interesting work as well.

Many of the snapshots of today, along with the news photos of our time, are in digital form. It is very likely that no “paper trail” will exist in the future for these kinds of images. The history of fine art photography is filled with images that were never intended to be considered fine art. Is this concept lost forever to future collectors and curators?

If so, maybe that is not such a bad option -look at all the bad stuff out there, and consider all the time needed to sort out the good from the dull.

You’ve spent a good deal of research time at the Vatican Photography Collection and recently received a Getty fellowship to return to Rome and continue your research. What special fascination does

this collection hold for you?

It’s mainly unknown work by unknown photographers from all over the world.

With John Szarkowski, you organized a major retrospective on Ansel Adams, in 2001, then curated a major retrospective of Szarkowski’s photographs that recently traveled to the NY MoMA. What’s next for SFMOMA? Any future plans for another major retrospective such as one on Van Deren Coke?

My next big project will be on voyeurism and surveillance. I’m working on a big exhibit about things that are forbidden to be photographed: like violence and death and sexual images. It is also about how we are watched and our ambivalence about photography. It is about a culture that is ferociously looking at images that are taboo.

SFMOMA is located at 151 Third Street (between Mission and Howard Streets) San Francisco, California. For general information call (415) 357-4000 or visit www.sfmoma.org.

Kay Kenny is a photographer, writer, and teaches photography at ICP, NYU and SHU, web: www.kaykenny.com, e-mail:[email protected]

Curator Interviews

Malcolm Daniel: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Published

1 year agoon

December 21, 2021By

Kay Kenny

During a weekday afternoon at the Metropolitan Museum of Art a few tourists straggle in and a woman with a traveling easel and unfinished copy of an 18th-century portrait passes by. Two educators compare their students’ drawings from the Pre-Columbian section. When we meet, Malcolm Daniel, newly appointed Curator in Charge of the relatively new Department of Photography, breaks into a smile. He assures me that while photography has only recently gained a department and curator of its own within this museum’s vast encyclopedic collection, it’s been around much longer.

Photography departments in university art schools were just beginning when you received your B.A. in Art History & Studio Art from Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut in 1978. Did your art history studies include the history of photography?

No, there wasn’t a history of photography program offered at the time. There is one now. At the time I was studying printmaking and painting. I had visions of being an artist and I was studying the range of art history from ancient to modern. I had a mild interest in photography.

In a way, the most important aspect of my education, one that shaped the career I would follow, was a semester spent in Rome where I had inspiring teachers and the experience of going into the city and studying art history by standing in front of the actual art object and architecture. It was that experience of contact with the real works of art and what you could learn from that contact, that confirmed an interest I already had of working in a museum. It was also true that the more great art I saw, the more humble I felt about my own range in the art world, so I became more and more confirmed as an art historian. I do think that as an art historian I’ve been helped by having had that experience of trying to make art myself. I have a better understanding of how those physical processes work as a result of my printmaking experiences.

Peter Bunnell was a leading force in the development of a History of Photography Program at Princeton University where you received your M.A. and PhD in 1987 and 1991. How did he shape your interest in photography?

That’s really where my interest in photo history blossomed. Before going to graduate school I worked in the education department at the Baltimore Museum -bout five years. While I was there I developed a deeper interest in the graphic arts in 19th-century France and in photography.

At Princeton, having the opportunity to work with primary material in the Minor White Archive, and Peter’s dedication to teaching history with the actual object – it was his instruction, his enthusiasm and his passion that ultimately led me into photographic history. I didn’t go to Princeton to study photo history! I went thinking I would do something in modern painting or sculpture then gravitated towards 19th-century France. I decided, however, to do something that excited me a lot: Work where I could make a contribution. That was the work I had done with Peter in an area of photography where there was still so much primary research to be done.

You were still working on your doctorate in 1990 when you joined the Metropolitan Museum as a curatorial assistant. That must have been an exciting time to be there just as Maria Morris Hambourg began working with Howard Gilman and Pierre Apraxine to shape the Gilman Paper Company’s Photography collection as a compliment to the museum. What was your role as her assistant with this enormously important collection?

Actually, I had been a fellow in 1987 and 1988 in what was then the department of Prints and Photographs and worked with Maria Hambourg at the beginning stages of my dissertation. We got to know each other. I then went off and did a year of research in the archives in Paris. I was writing my dissertation in 1989, 1990 when a position opened up and she held the job open for six months for me so that I could finish the dissertation before starting work. She knew we would work well together.

It was a very exciting moment in the department. We were on the verge of becoming an independent curatorial department. Certainly the great attraction of coming to the Met was the opportunity to work with Maria, whom I admired so much, still admire so much, and from whom I have learned so much, as well as the chance to work with a great collection in an encyclopedic museum. From the moment Maria came to the Met, in late 1985, early 1986, the relationship with the Gilman collection began to build. By 1990, they were already envisioning the exhibition “The Waking Dream” and that collaboration intensified. I’ve always worked with the whole collection but my heart has always been with the 19th century. It’s the period I feel the most passionate about and done the most research in, but the history of photography is relatively short and in this department we all contribute to the discussion about works from the whole history. Each of us have a special area, an area that we love more than others, but we all feel comfortable participating in discussion – that’s what makes it so exciting.

Your area of expertise is described as 19th-century French and British photography. Was it the Gilman collection that brought you to the museum or did you see the Metropolitan Museum’s on-going interest in early photography as a perfect compliment to your own interests? I’m referring to Alfred Stieglitz’s collection of turn-of-the century photographs and the photographs from the Ford Motor Company Collection.

Well, it’s not accidental that Maria Hombourg had a deep interest in 19th-century French photography, which was the area that my dissertation was in, the French landscape and architectural photographer Edouard Baldus. It was an area that she was interested in building within the collection. Part of that was the Gilman Collection, but we also made major acquisitions for the collection in 19th-century French photography since the moment Maria arrived. By the time I got here, the collection had two great strengths, the Stieglitz Collection, which had come in as a gift from Stieglitz in 1933, and the Ford Motor Company Collection acquired in 1987.

The Stieglitz Collection included some of the greatest works by Pictorialist photographers and members of the Photo Succession so we had incomparable strength from the period of 1895 to 1915. The Ford Collection assembled by John Waddell, a great New York collector, is a collection of 500 American and European photographs of an era between the two world wars. That extended our collection up to World War II. Maria’s task was to strengthen what came before the Steiglitz Collection and what came after the Ford Collection.

You have also been instrumental in acquiring work from the Rubel Collection and curated an exhibit in 1999, “Inventing a New Art: Early Photographs from the Rubel Collection.” How did that come about?

We had various opportunities throughout the 1990’s to acquire French photographs that trickled out from people’s cupboards and came through auctions and dealers and were pretty successful. We weren’t as successful with the British material. Part of that had to do with the market. In the late 1970’s and early 1980’s there was a great rush of British material to the auction houses as the photography auctions began in the 1970’s in London. Libraries and manor houses emptied out into those auctions as people discovered that there might be value in those old photographs, but the museum did not buy anything during those years! The study of the history of photography wasn’t developed enough yet. There weren’t the books, the tools, there wasn’t yet a connoisseurship, a sense of what the print should look like.

So, after the rush of materials to the auction houses, it all dried up. The William Rubel Collection gave us a second chance. He assembled the collection in the late 1970’s, early ’80’s when maybe only half-a-dozen people were seriously collecting. Rubel put together a very remarkable collection with enormous strength in British photography, particularly those four pillars of 19th-century British photography, Talbot, Hill and Adamson, Roger Fenton and Julia Margaret Cameron.

You founded the Alfred Stieglitz Society about seven years ago. Is this a special interest group dedicated to early photography?

We’ve always had a visiting committee, which is a kind of advisory committee for the department. It’s made up of prominent collectors and a couple of people from academia including Peter Bunnell and Eugenia Parry. She was the person who wrote the book “The Art of French Calotype” but we wanted a way to expand our circle of friends and supporters so we founded this friends group for photography from the past right up to the present. It developed into this very lively and supportive group of about fifty individuals or couples, most of them collectors. The members are by invitation, but we do welcome queries and the members do spread the word. Our one restriction is that it is not open to dealers or people involved in the trade. Members pay dues each year. There are events throughout the year that include visits to artist studios and to private collections, tours of our exhibitions and curatorial seminars working with the Met collections. We balance our program with 19th century, vintage 20th century to contemporary photography. For instance, this year Jeff Wall spoke to us at our first event of the year. We just made a major acquisition of Wall’s work. The main event is a dinner each spring in which the curators present works of art -cquisition and the members vote on what their dues money is to be spent on. Of course, all of the work we present is work that we want and most times we’ve been very fortunate and individual members have stepped up and said, ”If the group doesn’t vote for this, I’ll contribute the funds!” Usually we’ve been able to acquire almost everything we’ve presented.

You were appointed an assistant curator in 1993, the same year that “The Waking Dream: Photography’s First Century,” a huge exhibit of photography from the Gilman Collection, was exhibited. The Department of Photography was only created in 1992. What took so long for the Museum to formally recognize a department of photography?

Well, this museum collected photography before MOMA was founded. It’s important to us now that we are a separate department, but the Met began collecting photography in 1928. It was in the purview of the Prints department but we had quite visionary curators. The first curator of the Print Department was William Ivins followed by Hyatt Mayor. Both of them had an all-encompassing sense of what constituted the graphic arts. In the fifties John Mckendry was at the helm. He had connections to the fashion world and brought in a little more contemporary photography. When Weston Naef came in first as a college intern. then as assistant curator, he took photography as his bailiwick and focused on building the collection further. So there was a sustained interest but no pressing need to make it a separate department.

When Maria came in 1985 she was the first curator specifically hired as a photography curator and the first to have done her doctorate with a focus on a photographer. She came in as an associate curator prepared to lead such a department. It took a little time to establish it. She came in and built the collection through the Ford Motor Collection acquisition and made her mark through various exhibitions. The director and the trustees saw what she was doing and understood that photography had its own history. I think that it’s more remarkable that this museum has been collecting photography for eighty years than that it didn’t have a department of photography until 1992.

By the time you assumed the post of Curator in Charge, in 2004, the museum had already started to vigorously collect more contemporary photography. It seems as if the museum was trying to rapidly make up for lost time. Do you see a major shift in that direction at this point?

I think that’s true. We have always collected right up to the present day but as long as Maria’s been here and I’ve been here we have exhibited contemporary photographers. But I do think, with the acquisition of the Gilman Collection giving us such great strength in the first hundred years of photography and setting so high a standard in terms of image and print quality, that there would be fewer and fewer acquisitions of 19th-century and vintage work needed to fill the gap in our collection. Our acquisitions will be focused on the period from 1960 to the present and, of course, new work is being made every day!

Your curatorial interests, on the other hand, seem to remain largely in the 19th and 20th century. You curated the exhibits “Edgar Degas, Photographer” in 1999, “The Dawn of Photography: French Daguerreotypes” in 2003 to ‘04, and most recently “All the Mighty World: The Photographs of Roger Fenton, 1852–1860” in 2005. Do you see your interests changing with the museum’s growing interest in contemporary photography or is this an area that is dearest to your heart and likely to remain so?

Yes, my heart remains in the 19th century, there’s no question! I find it a remarkable moment particularly in the 1850’s when photography was fully mature and taken up by trained artists and yet it was still a hand-crafted medium. It hadn’t yet been industrialized. There were such glorious pictures being made by French and British photographers and American photographers.

Who, among your staff, advises you on contemporary photography? What kind of work or trends are they bringing to your attention?

There are two people. The first is Douglas Eklund; he’s an assistant curator whose area of specialty is 1950 to the present. He’s working on a show called “The Pictures Generation: Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince, and Laurie Simmons.” Louise Lawler is currently scheduled for 2009. It should be a great show! He’s the staff member who is most frequently out in the galleries, meeting with artists, meeting with dealers and collectors.

However, we also go out as a department once a month and Doug has usually gone out and done the scouting around and figured out what is most important for us to see as a group. The second person is Maria Hambourg, who after several years of being on leave has returned part time. After doing so much in the 19th century and early 20th century, what she’s finding most exciting is the contemporary world and she’s working closely with Doug in that area.

Now that the Gilman Paper Collection is officially part of the museum’s holdings, would you say that the Met has become the preemptive power in world-class photography collections? Any rivals to this collection of over 8,500 images?

Yes, there are rivals, but I think it places us in the highest rank. It’s very hard to compare collections. In terms of the 19th century our only rival is the Getty Museum. If you compare us to MOMA, certainly MOMA is stronger in classic 20th-century photography. If you compare us to the Museum D’Orsay, yes they have a stronger French 19th-century collection. If you look at the National Museum of Photography, Film and Television in Bradford, England, with their acquisition of the Royal Photographic Society collection, they have great strength in turn-of-the-century material like the Stieglitz collection. They have the second highest concentration of Pictorialist photography in the world and they have an unrivaled collection of 19th-century British photographers.

You participated in a panel discussion recently at the Met in conjunction with AIPAD. The panel’s theme was “Collaboration: Collector & Curator” and you shared the stage with Pierre Apraxine of the Gilman Paper Company Collection, as well as several other museum curator and collectors. Are you still working with Mr. Apraxine to acquire new works?

In an informal way. Pierre has a suburb eye and experience, so we ask his opinion about work few are considering -cquisition, or ideas for exhibitions. The next installation to open in the Gilman Gallery in February titled “Sight Unseen” is from the Gilman collection—photographs that have never been shown in the Met before. Pierre worked with associate curator Jeff Rosenheim to choose the work for the exhibit. We rely on Pierre for the history of that collection. He knows more about those pictures than anybody else. He was the curator for the recent exhibition “Spirit Photographs.”

While the Howard Gilman Gallery is a wonderful showcase for earlier photography it can’t accommodate the large-scale images of many contemporary photographers. Any plans to create a permanent gallery for this work? Do you foresee any future trends that indicate another great shift in the photographic horizons?

Yes, though the details can’t really be announced yet, funds have been donated and plans are very much alive – gallery of contemporary photography that would be appropriate in scale and space to view photography of our own time. Our notion of what constitutes a photograph is expanding so we will continue, carefully, and slowly, to acquire works of video and new media that seem to mesh with our interests in photography. It may be that the modern art department also collects in that area and we hope there will be communication and collaboration. After all, we are all one museum and I wouldn’t want to see the history of photography divorced from the contemporary expressions of that medium!

The Metropolitan Museum of Art is located at 1000 Fifth Avenue at 82nd Street, New York, NY. For general information call: 212.535.7710 or visit

www.metmuseum.org.

Happy Birthday, Berenice Abbott

New: Focus Magazine Returns To Print

GORDON PARKS: A CHOICE OF WEAPONS

Paris Photo 2021 Review

A Trillion Sunsets

Happy Birthday, Berenice Abbott

New: Focus Magazine Returns To Print

GORDON PARKS: A CHOICE OF WEAPONS

Arthur Tress: Finding Us In The Other

Dare To Go

What I Did Over Summer Vacation

Trending

-

Photographer Focus1 year ago

Photographer Focus1 year agoArthur Tress: Finding Us In The Other

-

Collector's Focus1 year ago

Collector's Focus1 year agoDare To Go

-

Collector's Focus1 year ago

Collector's Focus1 year agoWhat I Did Over Summer Vacation

-

Collector's Focus1 year ago

Collector's Focus1 year agoMagnum Photos

-

Vintage Focus1 year ago

Vintage Focus1 year agoBerenice Abbott

-

Collector's Focus1 year ago

Collector's Focus1 year agoSPEAKING OF TRENDS…

-

Collector's Focus1 year ago

Collector's Focus1 year agoGallery Trends

-

Vintage Focus2 years ago

Vintage Focus2 years agoFrederick H. Evans