But painting was his first great and overwhelming ambition. From 1934 to 1938, deep in the Depression, he attended the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art, drew from plaster casts and live models, learned the techniques of water color and oil, and chose Alexey Brodovitch as his major instructor. Brodovitch, the legendary art director of Harper’s Bazaar, through his design courses and later photography classes, influenced such photographers as Richard Avedon, Hiro, Lisette Model, Diane Arbus – and Irving Penn. He encouraged Penn’s design work and invited him to be his assistant at the magazine during two summers and to work with him on several personal projects. Occasionally, Brodovitch asked Penn to make small drawings, a few of which were published in the magazine. Penn was barely out of his teens.

For many years, aspiring artists yearned to be painters the way mountain climbers yearn to conquer Everest and little boys yearn to be president (or firemen). Though he had no intention of being a photographer, Penn bought a Rolleiflex as an aide mémoire with the money he earned from his drawings, and in fact he took photographs that already showed his strong sense of composition and graphic design. But what he wanted deep in his heart was to earn the honorific “painter.” In 1941, when he was working as an art director at Saks Fifth Avenue, the kind of job his art school classmates considered a stepping-stone to heaven, he quit to spend a year living on meager means in Mexico to devote his life to canvas. Irving Penn had determination bordering on obsession in his bones, determination to be the best he could and perhaps simply the best. This was coupled with a nagging uncertainty that he could reach that pinnacle, an uncertainty he never quite put to rest. That may be one definition of perfectionism, which he wore like a glove; one observer says he was not easy to work with, and “even objects had to comply” – when an assignment was to show the instant a tray full of glasses fell, he insisted that all the glasses, in all the trial shots, be Baccarat. Yet Penn’s steely determination drove past his insecurities onto high ground over and over again. He judged himself strictly: at the end of that year in Mexico he decided he wasn’t good enough to live up to his own standards, and he took his linen canvases into the bathtub and washed off every trace of not-good-enough. Later, he sometimes used his erased paintings as tablecloths.

When he returned from Mexico, Alexander Liberman, another extraordinary art director, hired him as an associate at Vogue. Penn did layouts and drew cover designs for photographers, who neither liked nor followed them. At length Liberman, who had seen some of Penn’s photographs, suggested he take them himself. Penn’s first Vogue cover, in 1943, was a color still life, the magazine’s first still-life cover. In 1944, Penn volunteered for the American Field Service, driving ambulances and taking photographs overseas until the end of the war. He then returned to Vogue and immediately began taking fashion pictures, still lifes, and portraits.

He was a modest man, private, formal, rather shy, and reticent. He spoke so softly that at times one might have been grateful for an ear trumpet. Scarcely the Hollywood profile of a revolutionary, even a revolutionary artist– yet by 1947 he had sweepingly revised the traditions of both fashion photography and portraiture (more on portraits later), and in time he would toss in the resurrection of a nearly-forgotten process as spare change. He began by throwing overboard all the standard procedures. Fashion photography in the 1930s, influenced by Edward Steichen and European sources, tended toward a cinematic and dramatic lighting, with elaborate poses and gestures, cleverly designed backgrounds, and suggestions of theatrical situations or narrative. Penn wiped the slate as clean as his linen canvases. His fashion photographs were exceedingly simple and pared down – context, story-telling props, and extravagant artifice had been removed as if by a scalpel in the hand of a surgeon intent on removing moribund tissue to reveal clean skin.

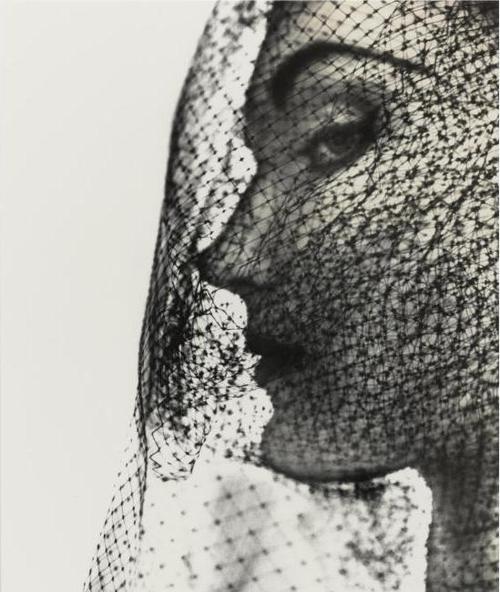

His light was soft, even, and clear, more like the liquid light of day than the strong light and hard-edged shadows that were de rigeur in fashion magazines. For years Penn daydreamed about a studio with a northern skylight letting in the light of the outdoors; the kind of light that nineteenth-century photographers worked with. In 1946-47 he designed a bank of tungsten lights on a ceiling track to approximate a skylight.8 Behind most of his fashion models was a gray and lightly mottled wall or a plain white sheet of paper setting off the stark blacks of clothing. In 1950 he would carry this kind of contrast to its logical, striking conclusion: a picture of Jean Patchett in a black jacket, white scarf and gloves, a black hat with a white band around it and a black veil. The image, without modeling and only a few tiny and faint shadows, was set against a bare white ground on the cover of Vogue, where all the type was black, and the model looked off to the side as if to avoid the photographer’s stare.

This bold graphic approach was particularly apt for the simpler, pragmatic clothes designed by young Americans conscious of shortages brought on by a world war and the new freedom women had found during that conflict. But the fashion world, having never seen such images, was up in arms; some vehemently against, some equally for. “For the first few years,” Liberman said, “Penn and I were thought of as dangerous destroyers of good manners in a world of ladies in status hats and white gloves.” It was not the first time and it would not be the last that an assault on good manners would change the manners themselves: in a few years magazines adopted Penn’s light, and for a while some photographers imitated his brash simplicity, never quite achieving his audaciously minimal elegance.

The first postwar years were a time for fresh beginnings, and Penn and Richard Avedon, Penn’s only real rival and equal at the time, both changed the temperature of fashion photography in highly individual ways. Avedon employed white backgrounds in his own manner to great stylistic success. When he photographed the Paris collections beginning in 1947, he took his models outside to street performances and set them in motion, descending stairs in swirling skirts that the French, after lean years, at last had sufficient fabric to create. When Vogue sent Penn to photograph the collections in 1950, he was delighted to spend his days inside an old daylight studio with a discarded theater curtain bearing all the marks of age upon it for backdrop.10 His pictures were immensely still; occasional stances and gestures wrote temperamental lines across the surface. His models were engaged in no activity but modeling and no encounter with anyone or anything but the camera; they were isolated within the proposition of displaying two objects of beauty and desire: the couture and themselves. Penn, an exacting craftsman, understood and communicated the delicacies of couturier design and dressmaking. He photographed fashion excerpts and minutiae, like a voluminous, pouffed sleeve or a gauntlet with a diaphanous kerchief attached to it. Fashion photography, today more focused on life style, no longer takes close-ups of details very often, partly because the skills that produced such details are no longer available in quantity.

In Paris Penn took one of the lasting icons of fashion photography, the picture of Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn – he married her in 1950 – in the Mermaid Dress, as well as other stunning pictures of the latest fantasies of female allure. The Mermaid Dress picture and a couple of others show the theater curtain’s edge and a bit of studio wall behind it, a signature mark of Penn’s, a reminder that the dress and make-up are not the only constructs; the studio and the photograph are equal players in that game. Penn was adept at undercutting the camera’s assumed realism and the carefully engineered seduction of his scenes when he wanted to, by saying, in effect, this is only a photograph, it’s a set-up, beware of being entirely taken in. Yet more intrinsic to his thinking is the fact that the curtain’s edge is irregular, a little rough, setting off the elevated glories of superb bone structure, figure, materials, and tailoring with a decidedly imperfect and evidently worn element – as if to say, “All good things must come to an end.”

This idea is key to Penn’s work and pervades it. Fascinated with entropy and preoccupied with decay, far more fascinated with the ultimate end of all things than with fashion, he injected reminders whenever he could into unexpected places. Fashion was in a sense what happened to him when he found work he could thrive on, but his curiosity was practically boundless. He once said to me, “I can get obsessed with anything if I look at it long enough. That’s the curse of being a photographer.”

When it came to faces and what he could find there, Penn (and minutes later Avedon) brought about what could fairly be called a revolution in studio portraiture by changing the nature of the relationship between photographer and subject. When Hollywood stars sat for Hollywood portraits in the 1930s, they expected to be turned into gods and goddesses of the screen, and so they were. Portraits of celebrated people in the immediate postwar years made a point of telling you who the sitters were or what they were famous for by referring to their work or their work spaces. Writers, artists, politicians, the famous of every ilk expected to be, and were, shown as the best of what they were and the best of themselves. People went to a studio to be flattered; it was their due. Penn turned that on its head.

He once made out a list of people he’d like to photograph; decades later he recalled, “I was shivering at putting these gigantic figures on a list.” His portraits removed identifying context and substituted for it two simple, unprecedented, inelegant, and psychologically charged settings. In 1947 he began with a rug he’d picked up when he passed a junk shop, one of those items that pleased him with its evidence of wear and tear and intimations of ultimate disintegration. Distinguished people came to lean on it, sit on it, drape themselves over it. Alfred Hitchcock looked like an overstuffed bag that had sprouted a suspicious head (Janet Flanner wrote Penn that this portrait “is a fine piece of monstrosity, practically straight Goya.”)13 George Jean Nathan and a world-weary H. L. Mencken were half hidden behind the rug, each with a hand to his chin and one of Mencken’s hands advancing between them as if it belonged to both. Christian Dior slumped on the rug like an empty sack, his head nodding off to one side, his body and legs weightlessly vanishing into blackness. These were (and still are) arresting pictures, as nothing quite like them had been seen before.

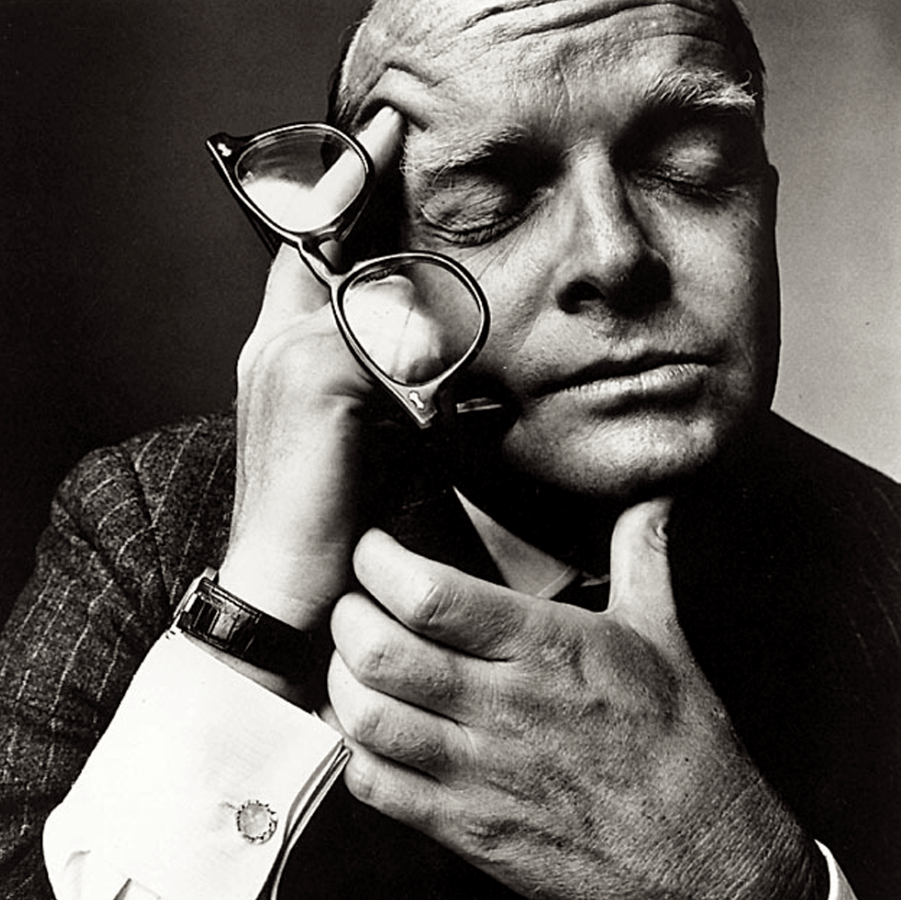

Penn also built a narrow corner from two studio flats and let subjects arrange themselves as they would; he said he invented it because he felt unequal to his famous subjects.14 Some of these images pull back to reveal the rough edges of the flats, emphasizing yet again the contrivance of the photograph and the imperfection of the means. Individuals reacted to this tight spot in individual ways. Marcel Duchamp leaned back comfortably against the corner with a little smile, George Grosz leaned forward anxiously in a too-small chair in this too-small space, Truman Capote knelt on the chair and huddled defensively in a coat that was so much too large it utterly defeated his body. (Penn photographed him again years later as a thoughtful man whose eyes are nonetheless closed to the camera and anything else worth seeing.) Georgia O’Keeffe shrank so deeply into the corner she seemed to be shriveling away. These people were in a tight spot and literally cornered, potential prey to all the anxieties left over from a war and a bomb that changed the world. They were also irretrievably alone, with no one to communicate with but the photographer. Penn said he didn’t direct them or make “very small talk” but might say something like, “How does it feel to you if you realize this eye looking at you is the eye of 1,200,000 people looking at you…?”

Penn flattered his models but not his heroes. He thought of himself as neutral, attempting to cut through the façade and find something the subject might not even realize was there. He felt not a shred of obligation to make his subjects attractive. Angry letters filled his mailbox. Georgia O’Keeffe so hated her portrait that Penn never published it in her lifetime. But he was not working for O’Keeffe or anyone else before his lens but for a magazine’s pages. He defined the largely unacknowledged but bedrock difference between a portrait commissioned by the sitter and one commissioned by a magazine: “Many photographers feel their client is the subject,” he said. “Karsh does. My client is a woman in Kansas who reads Vogue. I’m trying to intrigue, stimulate, feed her. My responsibility is to the reader. A severe portrait which is not the greatest joy in the world to the subject may be enormously interesting to the reader.”17 And in a sense his real obligation was to his very demanding self, to make the finest picture he could make, the devil take any lurking vanity.

His portraits were not only stunning, many of them enduringly so, but they opened the door to the kind of celebrity portraiture so familiar since the 1960s, distinctly unflattering but distinctive pictures which at length devolved into just-get-my-face-in-the-media-and-the-rest-doesn’t-matter photographs. Abroad in 1950 without his corner set-up, then back home later, Penn moved in extremely close to T.S. Eliot, Richard Burton, Henry Moore, Colette, Picasso. Picasso’s face was so deep in shadow and buried in a pulled-up collar and a pulled-down hat that all that emerged was barely half his nose, an ear, and a single burning eye. Colette was eighty and confined to bed; her husband said the picture “was a startling image, but was also an act of treachery, an intrusion upon her inmost being. It laid bare all that Colette liked to conceal – and doubtless something about herself of which not even she was aware…” Sometimes Penn got so close he cut off foreheads (see the sad face of S.J. Perelman, the writer of wittily amusing stories), and sometimes he placed his half-length subjects behind a table as if they were speaking to us at an uncomfortably close distance. Mr. and Mrs. Gilbert H. Grosvenor (he was the editor of National Geographic) sat behind such a table, he in bow tie, waistcoat with chain, and disapproving look, she with crimped white hair, wrinkles, and an air of caution, the picture a kind of upper-class Wasp version of American Gothic.

Penn was at least as interested in the lower strata of society and in less sophisticated societies in general as he was in the upper crust of adornment, good looks, or achievement. In 1948, when Vogue sent him to Peru for a fashion spread, he stayed on in Cuzco to photograph the inhabitants. He discovered a daylight studio and got helpers to bring country people to his door. Unaccustomed to posing, some of them even unaccustomed to cameras, they shook with nervousness and went rigid with fear. Penn posed them by hand with difficulty. He presented them centered and before a mottled gray backdrop, as formally arranged as any of his fashion models. Shoeless or tattered, they were entirely self-possessed, often with chins proudly lifted, in their hand-woven, multi-layered winter garments. Two barefoot children with raggedy clothes and adult faces hold hands upon a small table between them; a kneeling man steadies his imperious little girl on a table; three men sit on the floor, wrapped up in striped blankets and knitted face masks against the cold. Penn was surprised and touched when many of those fearful subjects turned up again the next day.19 Did they come for the money he paid them? Certainly, but the close and serious attention to themselves may have counted too. Penn spoke of certain unsophisticated subjects as being transformed when they came into the studio. Lionel Tiger, a sophisticated anthropologist, wrote about being photographed by Penn that he’d had a feeling “of giving more than I had, of being more than I was, of telling more than my story.”

In Paris in 1950, when Penn was photographing haute couture and celebrities, Liberman suggested that he make portraits of workers in the petits métiers, the little trades. The petits métiers, particularly characteristic of Paris, had been slowly disappearing for years; Parisian photographers like Atget and Brassai occasionally photographed those still at work on the streets. Vogue hired Robert Doisneau, who photographed all the nooks, crannies, and denizens of Paris, to find subjects for Penn, who didn’t know who Doisneau was. Penn posed a glazier, a coalman, a news vendor, a waiter, in their working clothes, full length before his favorite dappled backdrop, much as he had his fashion models, and was so captivated that he went on to photograph the little trades in London and New York – a rag and bone man; a sewer cleaner; a New York street photographer in a long coat beside a large-format camera on a tripod, looking like he might almost have walked in off a nineteenth-century sidewalk. Penn said the Parisians were suspicious but came for the fee, Londoners were proud, but the Americans were unpredictable: “In spite of our cautions, a few arrived for their sitting having shed their work clothes, shaved, even wearing dark Sunday sits, sure this was their first step on the way to Hollywood.”

All of these workers, beautifully lit with strong shadows on their faces and their dark clothes seldom admitting much modeling, stand tall and are often in bold poses. There have been times in painting and photography when full-length portraits cost more than half-length and under the circumstances favored the well born; the tradesmen, poised in the center with their accompanying implements, are as dignified as any aristocrat. Indeed, before the lens they have become aristocrats of their professions: entirely self-assured, even prepossessing, no matter what their gear or shabby clothes.

Penn could focus easily on widely varying subjects one after another, in part because he could become wholly absorbed in such a wide spectrum of things and people when he was behind his camera, in part because he seems to have regarded people from entirely different backgrounds and stations as equally interesting, possibly even equal. Certainly he took similar approaches to almost everyone who posed before him.

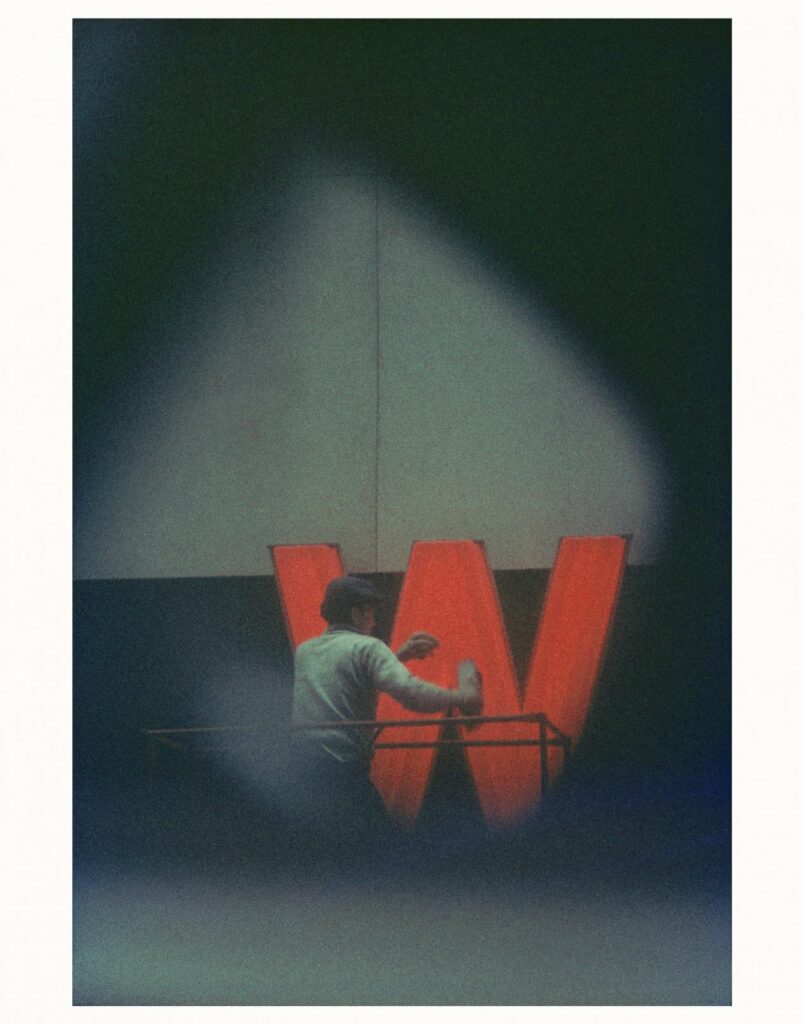

His interest in the lower echelons of society (and what might be called the lowest echelons of objects, which would later enter his still lifes) precedes his career. The photographs he made in the late 1930s and early 1940s, before he was a photographer, are very much of a time when photographers set out to witness a Depression, paid attention to people at the bottom of the economic ladder, and noticed how signs and advertising had become an environment as surely as paved streets had. He photographed poor blacks in the South and signs that were mostly hand-painted, “vernacular” notices, some of them missing letters or flaking off.

When it came to objects, he could make watermelon and gold watches as tantalizing as wishes, but his still lifes for Vogue alsomake clear that he valued the intrusions of everyday life into the carefully arranged paradises of commercial photography. “I began with still life,” he said, recalling his 1943 cover. “I didn’t have any sense of strength to deal with human beings at the time, either personal or photographic strength.” John Szarkowski, who curated a large Penn exhibition at MoMA in 2001, wrote that he couldn’t find any still lifes in earlier issues of the magazine and thought Penn probably introduced the genre to fashion magazines. Luscious in color, and generally luscious in black-and-white as well, Penn’s idylls of fruit and wine glasses, compotes and torn loaves of bread are anchored by gravity but often with only a nominal indication of a table to rest on. Then there are the intruders: a fly sits on a blazing yellow lemon; a charred match and its ashes lie by a perilously balanced composition of playing cards, dice, and poker chips; broken off cherry stems and a small beetle join the Elements of a Party. The results are a version of classicism with a view toward misrule and debility. He also photographed flowers for Vogue, magisterial red poppies and purple tulips heraldically set off by white backgrounds; afterwards, he photographed them as their petals wept their way to the ground on the path to death.

In Summer Sleep, a young woman, asleep beside a fan, a coffee cup, a piece of fruit and a fly swatter, is seen through a screen that flies crawl over – Penn affixed them, dead, to the outside of the screen with great care. And in The Empty Plate, an editorial photograph for House & Garden in 1947, the napkin is as crumpled as a piece of foil and the plate is full of food spatters, some of which have migrated to the table cloth. (Penn preceded artistic explorations more than once. The attitude toward food in The Empty Plate would be taken even further by Daniel Spoerri (who probably did not know Penn’s photograph), in the 1960s, when he hung on a gallery wall the remains of a meal eaten by Marcel Duchamp.) In Penn’s late still lifes for Vogue, in the 1990s, the objects themselves, rather than the leftovers or incidental intruders, could be disturbing – skinned frogs’ legs, an oozing oyster – and served up floating on a blank white page.

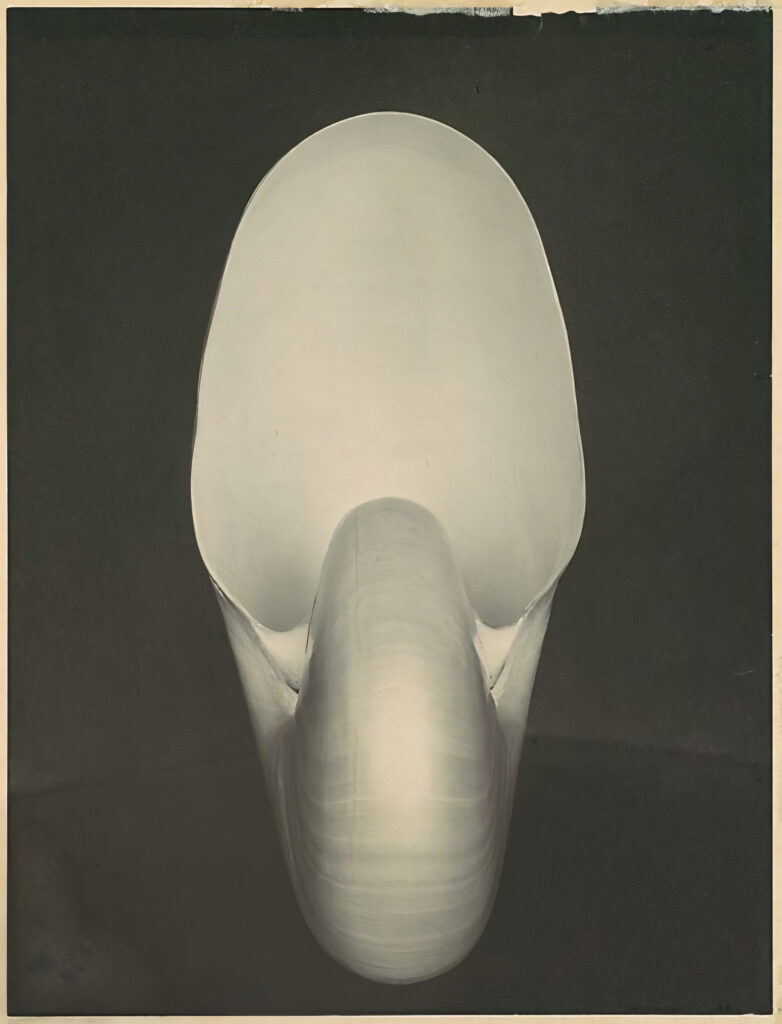

The unwelcome participants in the still lifes have some reference in seventeenth-century Dutch paintings where occasional insects, broken glasses and obvious memento mori like hour glasses remind us that these things too will vanish with time. Yet the mainstream of still life in the twentieth century – cubism’s pitchers and guitars, Giorgio Morandi’s bottles, Edward Weston’s peppers – was far more appreciative then premonitory. Penn was once again contradicting tradition.

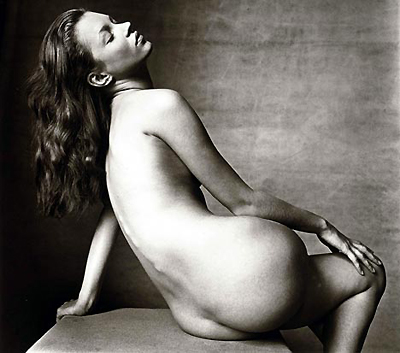

At the end of the 1940s, Penn made a series of nudes, using fleshy artists’ models, most distinctly unbeautiful (at least by conventional standards), all anonymously headless: the imperfect world in place of the manufactured dream of beauty in Vogue. Some were in contorted or ungainly poses or arranged like near-abstract sculptures. A decade later, when magazine production values had declined, he decided to print these pictures in platinum, once valued for its subtlety and artistic qualities. But platinum paper had not been manufactured for years, and the technique was virtually forgotten. Determined as always, Penn spent hours scouring the library and many more hours in the darkroom; by the late 1960s he had revived and elaborated on an outmoded tradition and an almost-vanished technique. The nudes were first shown in 1980; the postal restrictions in 1950 would have prevented their being published back then.

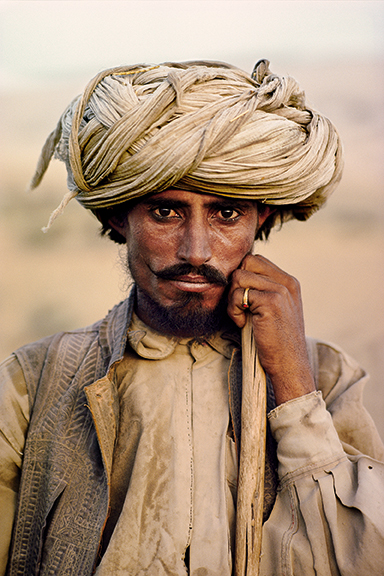

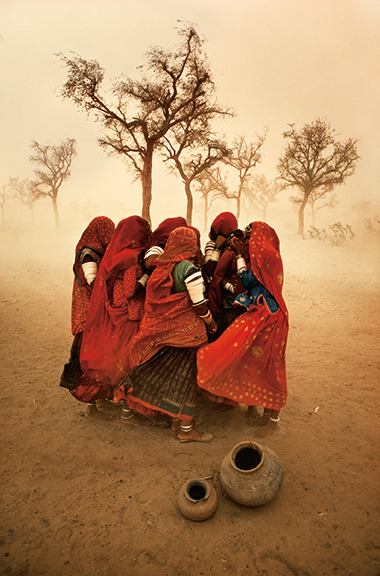

In the 1970s, Penn, smitten with the look of people from distant cultures and keen to photograph them, devised a traveling studio and took it to places like Morocco, Dahomey, Nepal, and New Guinea. He photographed people in their native costumes and posed them once more like his fashion models or celebrities, in the center of the picture against a washy gray ground, without props except for the weapons some carried. In Africa and New Guinea, the clothes, whether minimal or maximal, and the jewelry, feathers, nose ornaments, wigs, ornamental cicatrices, masks, and face and body paint were not merely strange to western eyes, but complicated, intricate, extravagantly artistic. The pictures were severely criticized. Penn was accused of treating native people as if they were outlandish fashion plates, exploiting them as the exotic Other. Penn explained his preference for studio photography over reports of daily life, saying he “had even developed a taste for pictures that were somewhat contrived. I had accepted for myself a stylization that I felt was more valid than a simulated naturalism.” He also noted that modern life so efficiently dissolved cultures that his photographs would become documents and preserve some part of a vanished world.

The anthropologist Edmund Carpenter had another thought, that these images not only “enlarged membership in the world community,” but they also “record a major change in human identity,” when people who had never seen themselves suddenly did so.”24 Carpenter also threw a raking light on the vexed issue of documentation. Penn made a photograph of Three Asaro Mud Men of New Guinea, 1970, armed with bows, arrows, and threatening mud masks. He posed his subjects by hand, as he didn’t speak their language, and discovered that in this culture, if you touched someone, that was regarded as an embrace and elicited a hug in return: “It’s a picture made up of a lot of double embraces.”25 Penn also related that “the masks recall a battle in which their remote ancestors, driven into a river by an enemy tribe, emerged mud-covered. Their attackers, thinking them evil spirits, turned and ran.”26 Carpenter, however, says the mud men were “invented” by Trans-Australian Airlines, which scheduled a lunch stop for a busload of tourists at a village halfway to their destination. Since there was no entertainment in that village, the airline designed costumes and dances that convinced tourists, a photographer, and generations of photography lovers that they had witnessed authentic native culture.

Penn’s work, which sparked debate the moment he started in fashion photography, continued to generate controversy. In 1975 the Museum of Modern Art exhibited his platinum prints of discarded cigarette butts, and two years later the Metropolitan Museum showed his platinum prints of urban debris; both caused what passes for an uproar in critical circles. Some thought art museums had no business showing work by a fashion photographer, others that the images were pretentious; still others questioned whether it was appropriate to record street trash in precious metal. Yet it would not be long before museums would be hanging fashion photographs on their walls and hosting an array of street trash in scatter-art installations. Once again, Penn was early. Artists would soon be replicating everyday objects in expensive metals, and the art vs. commerce conflict would begin to fade as the distinctions between high and low art were erased.

The cigarette butts, photographed vertically and monumentally as if they were crumpled and afflicted trees, and the run-over gloves and paper cups dredged up from the street, continued Penn’s career-long obsession with decay and death. Objects, too, suffer the universal law of mortality. A series of still lifes made several years later from pitchers, chunks of discarded metal arranged in precarious balance, bits of bone, and human skulls –perhaps not Penn’s most authoritative work – make the message unmistakable. Penn had long ago erected a barrier against the uncontrollable forces of entropy: a style of delicate balance and near-perfect elegance. “The world is only chaotic,” he said; “for me, the process is to bring order.”

But he repeatedly acknowledged that the laws of the universe trumped artifice, that insects would invade the most magnificent fruit bowl, that objects wore out, that time, disorder, and death won every match. As Robert Browning put it, “What’s come to perfection perishes.” And Issey Miyake wrote in the book of dazzlingly inventive photographs Penn took of Miyake’s clothing designs, “Maybe the really creative person is someone with a little touch of poison. Or a lot of poison.”Or a knowledge of the bitter taste of death.

Vicki Goldberg, an American photography critic and historian, resides in New Hampshire, USA. With expertise in the field, she has authored books and articles exploring photography’s social history and its impact.

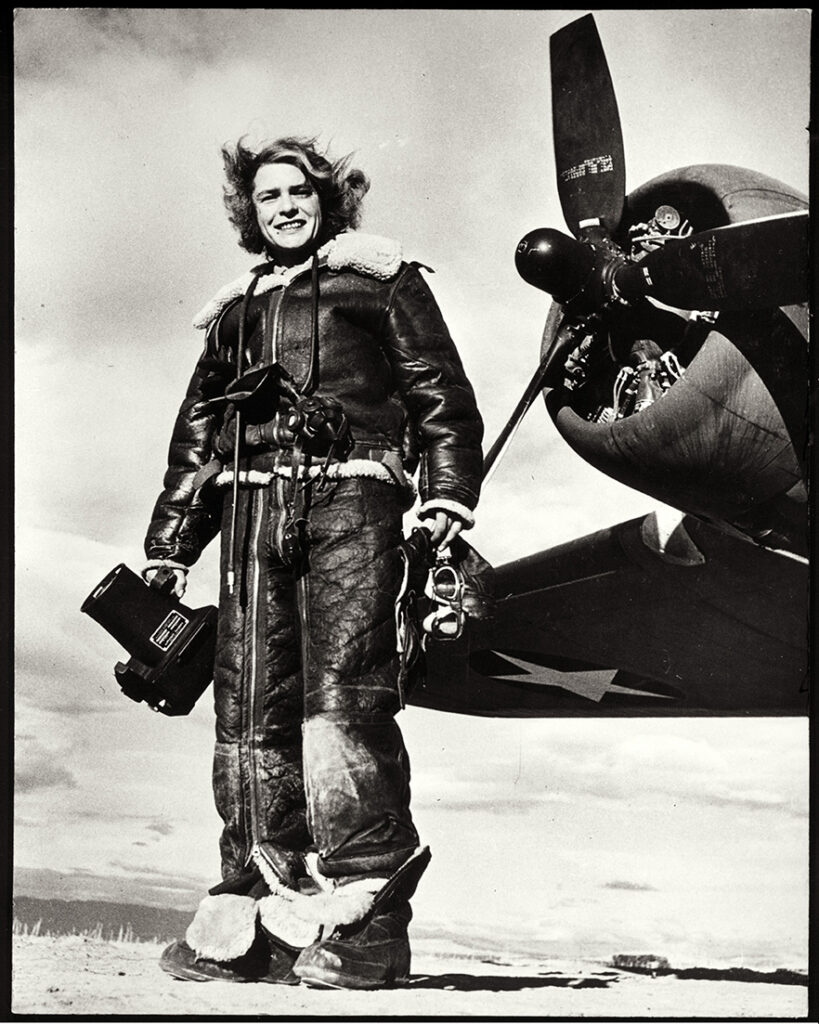

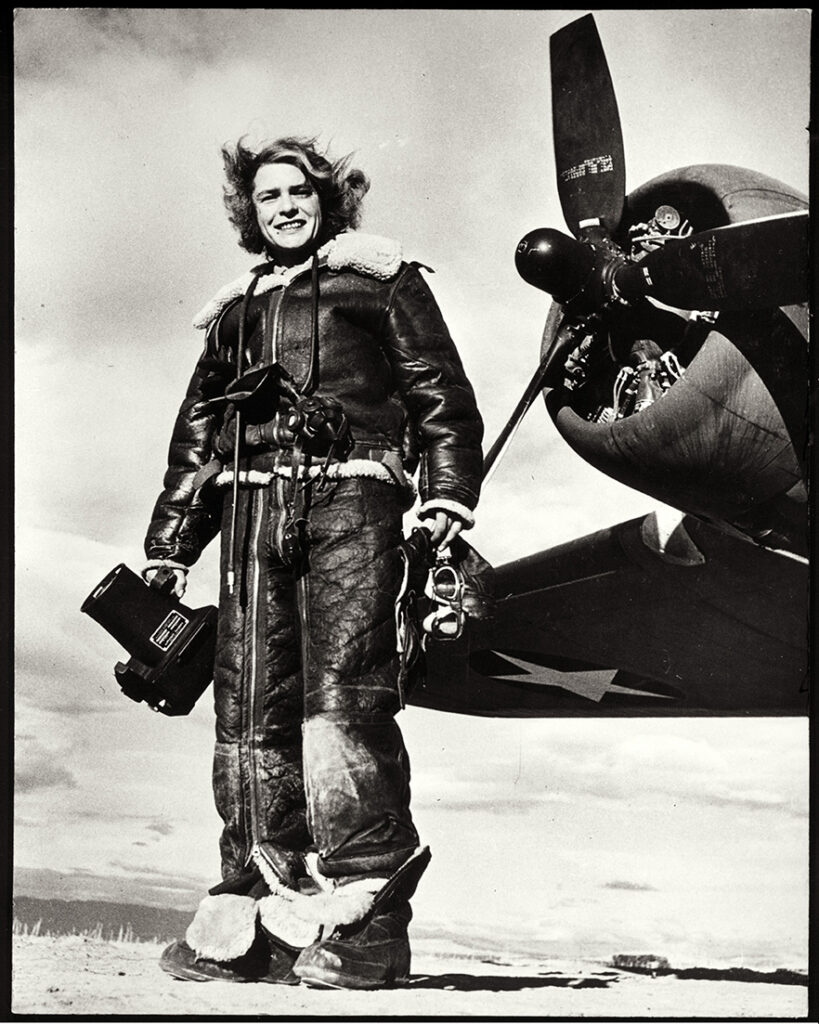

]]>To be there at the door of history, to know what it is like to live fully in one’s time and within the moment that is given, to know the direction of the blowing wind and to catch it and ride it. Margaret Bourke-White was bombed and survived, was strafed and survived, was torpedoed and survived, and she fell from the sky in a helicopter and survived. She dared high places—along the face of the new Chrysler Building in New York City, for instance—and she acted as one with the lowly and looked death in the eye. And when her own time came early, at 67, she died in a home where her wall displayed a poster-sized image of the trees she had photographed in Czechoslovakia.

Maggie the Indestructible began her serious work in photography with Clarence White, one of artists who led the process of defining a beautiful photograph early in the 20th century, and who established a school in his name, associated with Columbia University, where, in 1922, Bourke-White had enrolled as an undergraduate to study biology. Her elective study with White formed a strong orientation to the compositional priorities of Pictorialism, and she continued to fill the frame of her image with clarity and strength. That was her skill— filling up the frame, grandly, leaving little for guesswork.

After college (she graduated from Cornell University in 1927) her soft focus crystallized to a modernist’s hard edge. She found a subject in the musculature of the heavy industry in the Cleveland area. “A dynamo is as beautiful as a vase,” she said. And while her work followed the rhetorical lessons of Pictorialism, such as with the effective use of repetition in Hydro Generators, Niagara Falls Power Company and Fort Peck Dam (the cover image from that first Life magazine, November 23, 1936), it became something else. Yes, she took the lesson from Arthur Wesley Dow, the early 20th century critic and lecturer she heard at Columbia, who argued for the dramatic effect of a slice of light or rake of shadow. This affect appears dramatically in Romance of Steel, with a title still clinging to the connotations of a previous era. The image won first prize in the 1930 Cleveland Museum of Art regional exhibition. But Bourke-White’s sympathies were elsewhere—no longer with the connotations of soft focus. Her lens looked hard at just what was out there. New technologies had grown up in this fast changing 20th century. Her photographs carried the banner of change, and the tough mind and hopeful spirit of a New Deal.

She quickly rose in opportunity and fame, as Henry R. Luce’s favorite photographer. He discovered her and in 1929, brought her on for Fortune, his new magazine, and for its first year, she was the magazine’s only photographer. Then in 1936, Luce brought her over to his new Life. Bourke-White was confident, tough and smart. She got it done, and usually better than expected. That first cover, assigned to reveal the largest earthen dam in America, developed in her eye as a story about the new life on the frontier, now on the shoulders of technology rather than cattle, not simply a story about a big public work. She had covered the industrial development of Russia and had been the first outsider to gain permission there. She knew what she was doing, and how to look around corners for the full story. Her powerfully designed, bold-yet-simple compositions captured the Soviet’s sense of themselves as an emerging power. Then she photographed the Dust Bowl in the Midwest and sharecroppers in the South. She worked with the novelist Erskine Caldwell, later her husband of three years (1939–42). Their fine book together, You Have Seen Their Faces, about the Depression South, is not sufficiently recognized. If it takes liberties with quotations, it remains assertively true to the facts of the matter of poverty, and it effected significant social change.

When she had the chance, she took the liberty to pose and design a shot; she was notorious for packing hundreds of pounds of gear, including multiple flash setups that she employed to render the dark insides of industrial sites that attracted her. She overshot and counted on her assistants back at Life, a staff the envy of her colleagues, to process and print, when feasible, to her specifications.

Her work, almost always made for publication, is rarely signed. Of the 335 images (and 75 contact sheets) by Bourke-White in the George Eastman House collection, only three are signed, “Bourke White” on two lines, with a great flourishing “W”, though she also signed her full name more modestly, too. Two of the images are signed on the mount in the lower right, and one on the print in the lower left. The remainder is stamped by her—“A Margaret Bourke-White Photograph”—with the stamp or copyright of the originating publication.

She also published with The New York Times Magazine and the short-lived liberal newspaper without ads, PM. Finally, she created several portfolios—one with Time-Life just before she died, another about Russia in the early ’30s. Bourke-White was first in line to cover the Second World War in North Africa and in Europe, following General Patton into Germany and documenting the concentration camp horrors of Buchenwald upon cease-fire. “Nothing attracts me like a closed door,” she said in her autobiography, Portrait of Myself in 1963.

The late Jack Naylor, a pilot during the war who became a prominent collector of photographs and photo technology, remembered clicking the shutter of her camera for her breezy self-portrait in front of his plane. He would take her on reconnaissance flights and into combat, and recalled her fearlessness and fierce determination to get the image. After the War, she continued to report on the conflicts in India over partition with Pakistan, and on labor conditions in the mines in South Africa; and later on, the guerilla conflicts after ceasefire in Korea. Only the development of Parkinson’s disease slowed her and eventually brought her career with Life to a halt in 1957. She died in 1971.

George Eastman House has all of her books and those about her. Time-Life Picture Collection in New York preserves her negatives. The largest collection of her work is held by Syracuse University. Other large collections are held in the Cleveland Public Library, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the Library of Congress and the Museum of Modern Art. In two separate books, Vicki Goldberg and Sean Callahan write well about her life. Farrah Fawcett portrayed her in a 1989 television movie, Double Exposure, and Candice Bergen portrayed her in the 1982 theatrical release, Gandhi. John Szarkowski, writing on his appreciation of the collection he curated at the Museum of Modern Art, termed her “one of the most famous and most successful photographers of her time,” praising “her combination of intelligence, talent, ambition and flexibility….” Said Bourke-White, “Work is something you can count on, a trusted lifelong friend, who never deserts you.”

Anthony Bannon is the seventh director of George Eastman House, the International Museum of Photography and Film in Rochester, New York.

]]>

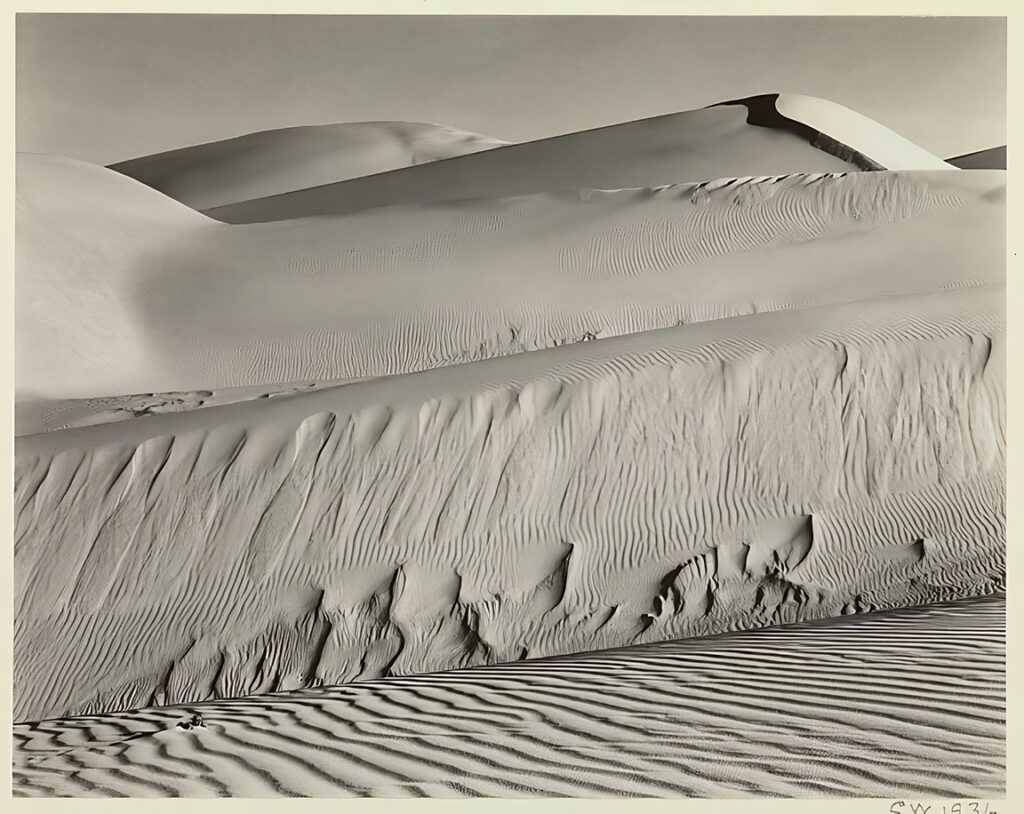

It was in the year 1923 when Weston came into what would be his own. He had been to New York in 1922 to visit the aging guru, Alfred Stieglitz, and received approval for his new work, which was a tough-minded, tectonically articulate appreciation of the Armco Steel Mills in Middletown, Ohio. So it was in 1923 when Weston left his wife and children to travel with his lover, Tina Modotti, to Mexico, where they remained for the next three years. He also was leaving behind his old way of working, abandoning the soft focus, restrained gray scale of pictorial imagery for a more declarative modernism. This also was a vital period in Mexico, a revolutionary time for the arts and culture, with great humanist expression from Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Frida Kahlo, and Miguel and Rose Covarrubius. In 1926, Weston finally returned to family and home in California; it was his 40th year. In 1928, he opened a San Francisco studio with his son Brett, and then moved to Carmel, where he remained until his death in 1958.

Weston was born in 1886 in Highland Park, Illinois, near Chicago, where he grew up. He began to photograph at the age of 16 after receiving a Kodak Bull’s Eye #2 camera as a birthday present from his father. His first photographs captured the parks of Chicago, where he lived at the time. An indication of how seriously he took this beginning is his commemoration of his 50th anniversary in photography in 1952 with a special portfolio.

In 1906, Weston photographed professionally in Chicago and California; he attended the Illinois College of Photography in 1908. He worked in California as a door-to-door portrait photographer or as a studio printer. He married Flora Chandler in 1909, a wealthy woman seven years his senior; her father was successful in real estate and later became publisher of the Los Angeles Times. Edward and Flora quickly had four sons, Chandler (1910), Brett (1911), Neal (1914) and Cole (1919). Between 1911 and 1922, he operated his own portrait studio and made pictorial salon images, successfully entering international competitions and exhibitions. With many, Weston perceived the shifting tenor of culture at the end of World War I. The case for fine art photography had been won; it was a time to see more clearly and understand more directly. Photography, rather than trying to be richly connotative, should depict “the very substance and quintessence of the thing itself,” Weston declared. Through the 1930s, Weston enjoyed publication and significant exhibition, work with the WPA Federal Arts Project in New Mexico and California; and in 1937, the first Guggenheim Award made for photography. In 1938, Weston married Charis Wilson, with whom he had lived and photographed since 1934. She is the model for much of his work during this period, and together they published two books, The Cats of Wildcat Hill and California and the West. They were divorced in 1946. Weston was a founding member of Group f.64, which included California-based artists Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham and Willard Van Dyke. Suffering from Parkinson’s disease, Weston ceased exposing photographs in 1948. His sons Brett, then Cole, took over printing his work for him. In 1955, Brett took on a project to make eight prints each of 1,000 negatives Edward selected. These were called the “project prints,” and about 800 negatives were realized. He died on January 1, 1958, in Carmel.

George Eastman House holds more than 250 prints by Edward Weston, including a collection of personal images he made with Tina Modotti in Mexico. Gustavo Lozano, an Andrew Mellon Fellow in the advanced residency program at George Eastman House, has been studying the Museum’s Weston holdings. He reports that during his formative years in the 1910s and early ’20s, Weston’s photographic technique was influenced by the dominant Pictorialist aesthetic of the moment. His photographs from that period were printed by contact on matte platinum, palladium or gelatin silver paper. Later starting around 1922, Weston progressively abandoned his romantic, diffused aesthetic and shifted towards a more objective form. He began using sharper lenses, a large format camera with sharp focus in every plane and printed (still by contact) on smooth, glossy gelatin silver paper without retouching. Lozano, formerly the photography conservator at the National Library of Anthropology and History in Mexico, observed that Weston’s lenses were a very expensive anastigmat and several soft focus, among them a Wollensak Verito and a Graf Variable. George Eastman House has in its collection a Rapid Universal Lens (Bausch & Lomb Optical Company, Rochester, New York) inscribed, “To Brett – Dad ’37.” Weston made use of a 3¼ x 4¼ Graflex camera, a 4 x 5 RB Auto-Graflex and an 8 x 10 Eastman View No. 2D.

The inscriptions in Weston’s prints changed over time, Lozano notes. In his prints from his early works until the ’20s, Weston signed in full, dated and inscribed his prints with pencil below the photograph and sometimes along the bottom edge on the mount. In his late works and particularly in his last two big projects, the “50th Anniversary Catalog” and the “Prints Project,” the full signature in script is transformed into the printed initials “EW” and the date, and the title was no longer included. The Weston legacy has been that of carefully rendered, finely printed work without complex manipulation. Weston’s style was to use simple materials very well. It is an axiom that has sustained his regard into our time.

Anthony Bannon is the seventh director of George Eastman House, the International Museum of Photography and Film in Rochester, New York.

]]>

At the time of this interview, The Jewish Museum in New York City is presenting Isaac Bashevis Singer and the Lower East Side: Photographs by Bruce Davidson.

Spanning the years 1957 to 1990, the exhibition features 40 intimate photographs of Singer, the revered Yiddish author, as well as residents of the Lower East Side Jewish community, including visitors to the Garden Cafeteria in that location. Could you tell us a little about your relationship to both Isaac Bashevis Singer and the world of the Lower East Side?

Isaac Bashevis Singer lived in our building here in New York on the fifth floor. I had photographed him years before on a magazine assignment. We just became neighbors. Also, I was interested in trying to find out about his world because that was the world of my grandfather. I wanted to find continuity. My grandfather came to the United States from Poland as a boy of 14. He learned English, became a tailor, and had a very good business. He went from being a tailor into manufacturing with his older son Leonard and Leonard’s wife Ruth, and that company is very large now.

I was born in 1933 and grew up in Oak Park, Illinois. My mother was a single parent. She was working in a torpedo factory during World War II. My brother and I could really fend for ourselves. We were very self-sufficient. We learned to cook. We learned to clean. We learned to meet our mother on time at the bus stop and carry home very heavy packages of groceries. My younger brother became an eminent scientist. I became a photographer. That was all part of being with my grandfather. For a while we lived with my grandfather in the home my mother was raised in. I began to sense there was something strange about my grandfather, there was some secret. There was something he left behind and he never really talked to us about it.

I was the first son in our family at that time to be Bar Mitzvahed. Our synagogue was a small clubhouse synagogue. I mean it was not a synagogue at all; it was a clubhouse with a small congregation. While I was reciting the Hav Torah during my Bar Mitzvah, I could see a box that I knew would be a camera on the rabbi’s desk. During the 1940s, cameras were scarce. Film was scarce. I had been taking pictures since the age of 10, and was very excited about receiving my first good camera and two rolls of film.

I was taking pictures and my grandmother emptied out a closet in the basement where she stored bottles of jelly. I began developing and making small contact prints in it. I even wrote on the outside of the jelly closet — I mean, it was small; I could barely fit in it — but I wrote “Bruce’s Photo Shop.”

You know, there is a similarity between photographing and tailoring. You learn to make the pockets straight, and actually you have the persona of the person you are fixing the jacket for. The persona is definitely there. It’s craft. And photography has craft also. So my grandfather sewed buttons and I sewed photographs. So I would say that entering the world of Singer and the Lower East Side was really entering the world of my grandfather, but I am in no way an observant Jew.

As a Midwesterner transplanted to New York, you have demonstrated your great love of the city and its inhabitants in many series of photographs. Could you expand on your feelings about New York and how the city inspires you?

The town of Oak Park was a very small community. It was the home of Frank Lloyd Wright and Ernest Hemingway. I have said that I am not a practicing Jew, but I am in the sense that wherever I photograph in New York — or wherever I photograph anywhere — it becomes to me a spiritual space in that I think there is a solemn responsibility when you have a camera.

Although I don’t read the Torah, I do read the Torah of life, and my own personal Torah, so it wasn’t a big deal to leave Illinois to come East, to go to school, and to explore New York. My very first day in New York — my mother had remarried and we were staying at the Plaza Hotel — I began to explore. I went outside the hotel and I was photographing the pigeons and people with my Rolleiflex. My mother or my stepfather came out and said, “You’re using up all your film.” I think New York is probably the most important and the most alive city in the world. It’s the most diverse. It’s the most difficult. It’s the most challenging.

I have found that over the years I have been able to enter worlds within worlds in the city, beginning with the Circus series, then the Brooklyn Gang, and later the Subway and Central Park, and other entities. I entered worlds within worlds and they became sacred places for me. I no longer entered a shul; I entered the sacred space of people’s lives.

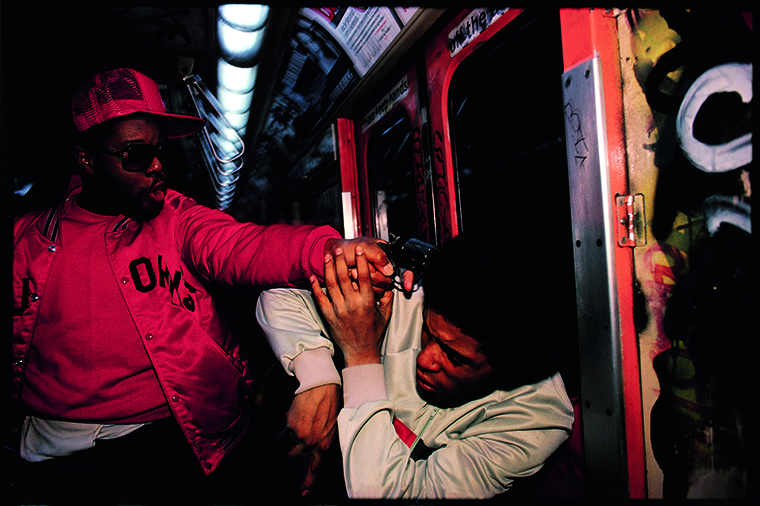

You have compared the New York City subway to the Theater of the Absurd. Do you still think of it this way?

Yes, but it is also the most democratic space in the world. Anybody, rich or poor, healthy or unhealthy, rides the subway. The graffiti at the time was written all over the place and was what is called the hieroglyphics of anxiety, of anger, of frustration, of “I am invisible but my marking remains.” You know, dogs pee on a pole but graffiti artists draw their name. The dog says, “This is me. I am here.” They’re making their marking and then somebody else comes over and pees on that marking and makes a new marking; so that was the dynamic. But the subway could be excruciatingly beautiful. It could be the sexiest environment I’ve ever been in; we can’t go into details but the subway can really be sexy.

How did all this relate to the mood of the city at that time?

At that time, about 1980, the trains were running poorly. They were very unsafe, there were a lot of muggers, there was graffiti written all over the place. I think the city was in default at that time, also. It was a chaotic, neurotic, pathetic time. And I chose…the subway really chose me. I started to go into it with a camera out, with a flash. A safari hunter. In fact I fashioned myself after the tiger hunter Jim Corbett. His books were written for boys but I liked them. So I became the tiger hunter. When you hunt tigers you have to watch your back. Anyway, I had all sorts of fantasies going because that’s what the subway can be. It could become as sacred as a church pew, it could be beautiful, it could be upsetting, it could be depressing. Anything goes, and I fed on that.

You have stated that your work in the subway was an antidote to depression. How was that so?

Because the subway was more depressed than I was. And in photographing in color — I wanted the color to be vibrant — I drew a parallel between fish in the deep sea where you see no light and yet you have iridescent colors when light is shown on them. I wanted to transform the subway in some way so that from a beast I made it beautiful and when it was beautiful I made it bestial, so that anything could come to me or reflect off me and rebound in the subway. I left my imagination and awareness open to the moment. The color experience was also a human experience.

Did you find it an experience of loneliness?

Yes, I seem to be attracted to things in transition, things that are isolated, maybe alone. I gravitate to that which has a certain tension because it’s in transition. The circus was in transition from tent shows to coliseum shows, from small, intimate family circuses to large extravaganzas.

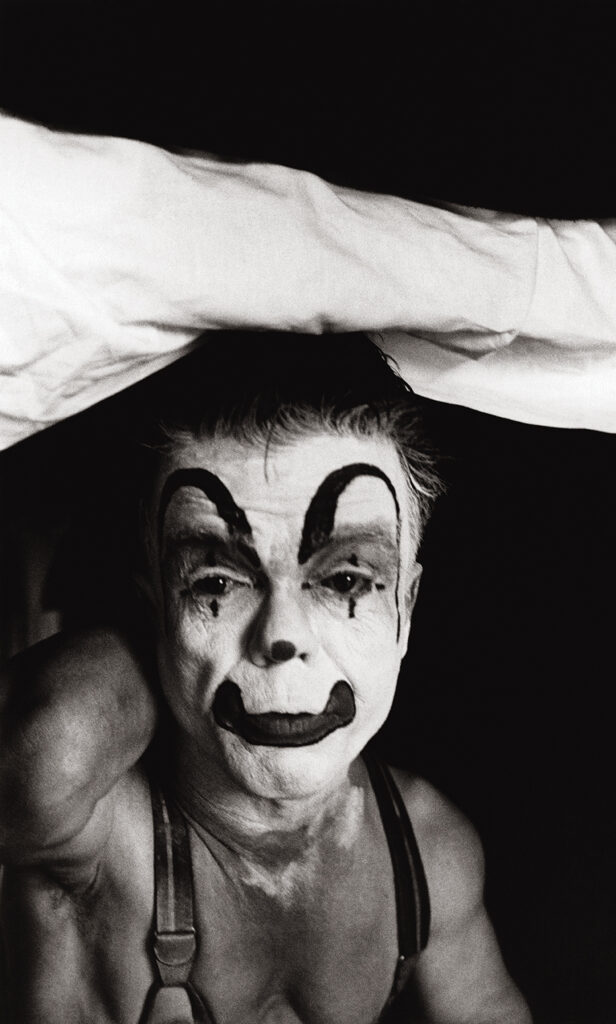

Let’s talk about your circus photographs. Historically, many artists of the 20th century, such as Pablo Picasso, Alexander Calder and Walt Kuhn, have been drawn to clowns and the circus. What do you think is the source of the appeal and how did you yourself get started with the circus?

Magnum in New York had an incredible picture librarian by the name of Sam Holmes. Sam was an amateur trapeze artist. He was the one who told me about the circus in Palisades Amusement Park in New Jersey, which was the beginning of my circus work in 1958. I was not drawn to the circus per se, but to the clown who was a dwarf.

It was the combination of attraction and repulsion that I felt standing next to him outside the circus tent that drew my attention and sustained a friendship with him. His name was Jimmy Armstrong. He was melancholy. He was sensitive, very sensitive to everything. He wasn’t depressed but he was poetic. It’s almost like he was a performance artist. Even when he was outside the tent, he was performing; he was directing the camera to what he could feel at the time. I never said, ”Jimmy, why don’t you pick up your trumpet and blow it.” I waited for him to do it. He worked hard in the circus. He was carrying two heavy buckets of water. And you know, people in the circus liked him. I have a picture in the Circus book of a roustabout giving him a massage. He didn’t have to do that. But that was the nature of the circus, too — they were a family.

They were kind of like Magnum, but with elephants. Jimmy and I had a very silent friendship. I just observed him. He allowed me to observe. He also allowed me to see things that might have been embarrassing for him, or even dangerous, like walking through a crowd of children. You know children can be quite cruel to dwarves. Where else can you find someone with the same size head as your father, but half your size? At the end of our two-month trip together I bought him a Yashica Rolleiflex-type camera that he could hold in his hand. He often said that I was his best friend, even though I wasn’t really close to him, except in the sense that I was with him all the time. What made it so compelling was that we all have a dwarf in us, and that dwarf can come out in various ways: something small and compressed as being repulsive.

The picture I took of him peeking out of the van [on the cover of this issue] is an early ”confrontational” photograph. It isn’t that other photographers hadn’t done confrontational photographs, but it was something that wasn’t usually done. In photojournalism at that time you were supposed to be the “unobserved observer.” So no one looked at the camera because the camera wasn’t “there.” Here I made the camera “there.” I think that was a very penetrating thing.

The fact that Jimmy Armstrong, the clown, allowed me that close into his soul was important to me. He was married and had children. He married a normal-sized, but short, woman named Margie. Jimmy is dead now, and Sam and I can’t seem to find Margie. Sam found out that Jimmy, during World War II, could crawl into the fuselage of the bombers to do wiring. So he joined the war effort as a dwarf. He had a lot of lives. He was a musician. He was photographed by many different photographers, including André Kertész. He was even in a movie, Cecil B. DeMille’s The Greatest Show on Earth (1952) with Charlton Heston and Betty Hutton.

After I left the circus, he sent me a route card every once in a while. This was his schedule, so I knew where he would be. I would call the chief of police of a town and say, “My cousin is a dwarf in the circus. Could you get a message to him?” The chief would assume that I was a dwarf too, and he would jump into his car and run out with the message, “call me,” or whatever. Over time I lost track.

Going back to the period of your life following Yale, you were in the military from 1955 to 1957. Was there anything about that experience that relates to your photographic work?

Absolutely. In the army, I was in the Arizona desert for about a year. I used to hitchhike to Nogales, which was only 40 or 50 miles away, to photograph the bullfights. Patricia McCormick was a female bullfighter and I became somewhat friendly with her. In hitchhiking to Nogales I came upon a small town called Patagonia. It was really a railroad siding and a bar and a gas station and a post office and that was about it. There I met an old guy who was driving a Model T Ford and we became friendly. He was a miner.

Every weekend I stayed at his bunkhouse and photographed. As I look at that body of work now, it seems very whole to me and I find it amazing. It was the precursor to the Widow of Montmartre, which I made the following year, when I was transferred from Fort Huachuca, Arizona to Paris, France. There I met a French soldier who invited me to have lunch with him and his mother in Montmartre.

After lunch I was standing on the balcony with my Leica and I saw an elderly woman hobbling up the street. I took a picture. The soldier said, “Oh, that woman lives above us and in fact she knew Toulouse-Lautrec, Renoir and Gauguin.” She was in her 90s in 1956, you see. She was the widow of the Impressionist painter Leon Fauchet. So the soldier introduced us and that series became the Widow of Montmartre. I lost track of that soldier for many years, but recently found him. He still lives in the same area. He’s one of the painters at the top of the hill in Montmartre.

At that point in my life I decided to show my work to Magnum Photos in Paris and to Henri Cartier-Bresson. Well, actually I had no idea of Cartier-Bresson. He was beyond reach. I left my photos at the Magnum office. They called me and said, “We would like to show your work to Cartier-Bresson.” Then I had an appointment with him, and that was the beginning of my career, and my life in photography.

Henri Cartier-Bresson is known as one of the most influential photographers of the 20th century. What was the effect of Cartier-Bresson on you and your work?

Cartier-Bresson took me under his wing. He tried to get me to read more, to reflect more, to be more disciplined. Over that year we had a professional relationship in which I occasionally showed him my work. Of course he had seen the Widow of Montmartre contact sheets. In fact, I just donated those vintage contact sheets from 1956 and about 17 prints to the Fondation Cartier-Bresson in Paris.

Cartier-Bresson is known for developing the concept of the Decisive Moment, one definition of which is the moment of stillness at the peak of action. Do you see yourself as being influenced by this idea?

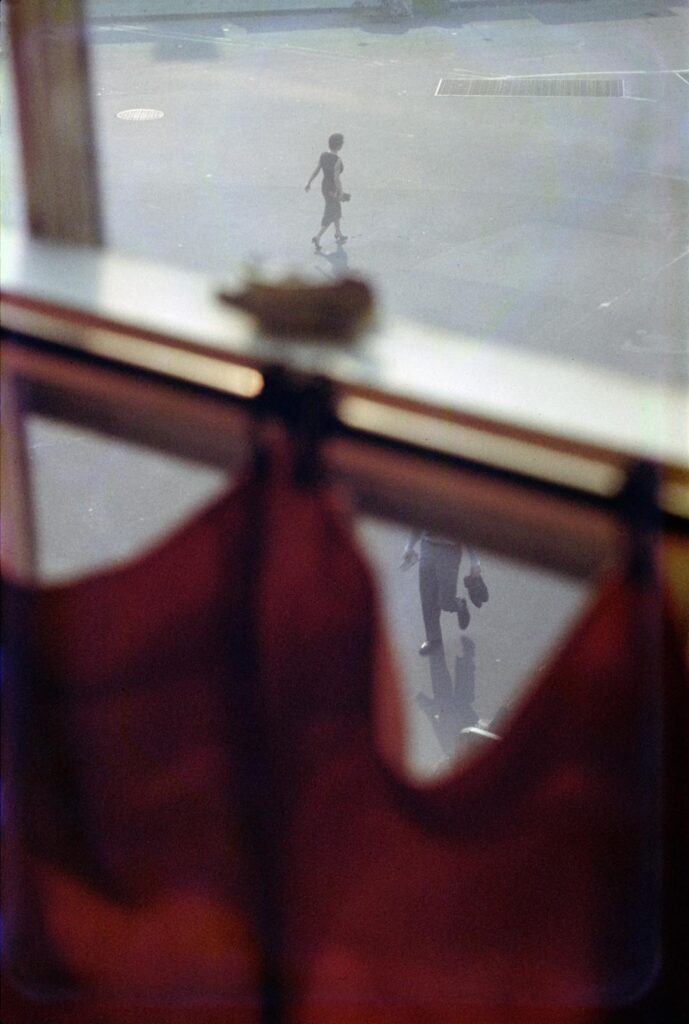

Well, the concept of the Decisive Moment has never been absolutely clear to me. To me it’s the Decisive Mood, and not the moment. I think that, sure, there is a decisive moment in life in everything we do. There’s a certain timing. But it isn’t just about timing, a man jumping over a puddle.

The Decisive Moment is an internal thing. If you become decisive and you enter life in a decisive way, the moments will appear, as long as you are in tune. So what we are really talking about is a way of looking at life, a kind of balance. Sure, there’s geometry, there are moments and all that, but my photographs are more of a mood and they are cumulative, too.

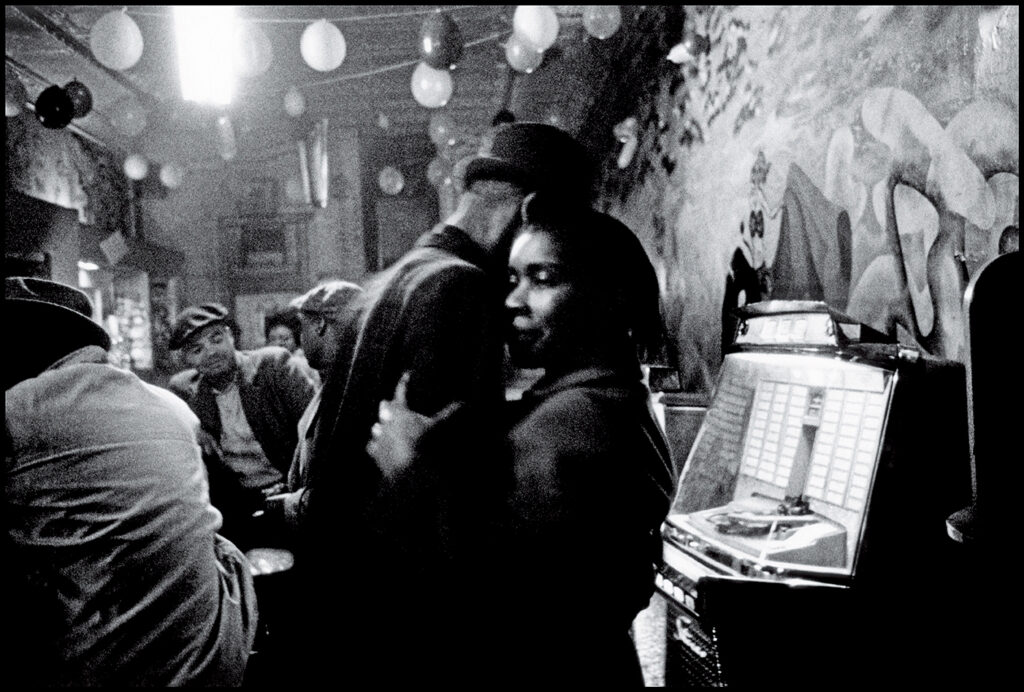

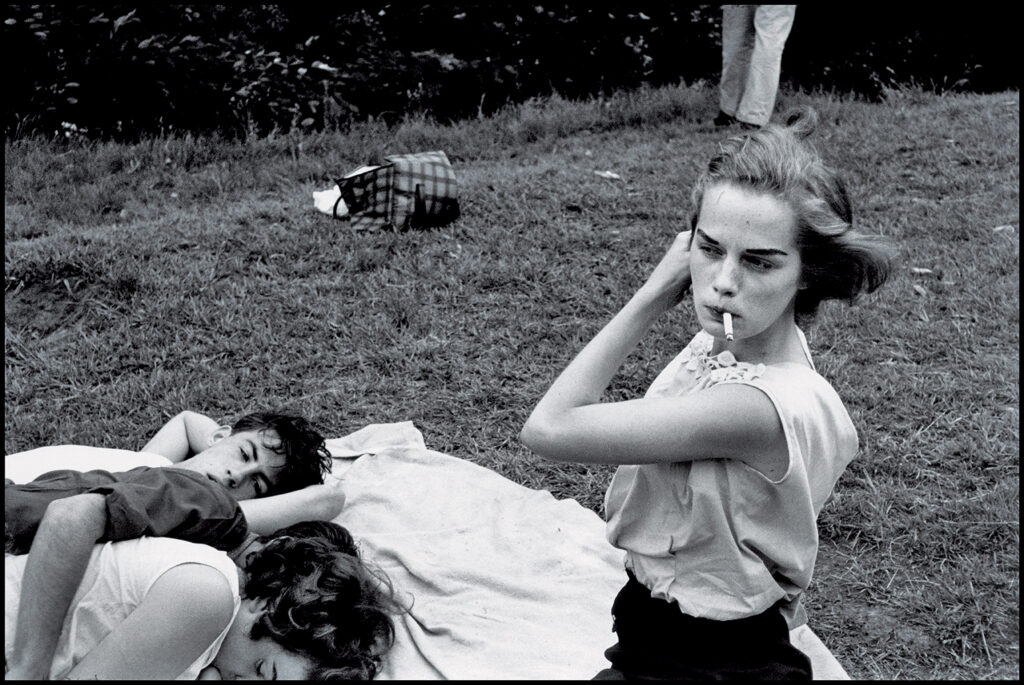

You did your series on the Brooklyn Gang in 1959. It was published in Esquire Magazine that year, but it did not appear in book form — Brooklyn Gang, published by Twin Palms — until 1998. One critic has described the essay on the Brooklyn Gang as having an air of innocence about it. Do you agree with that?

Those kids, at that time, you see, were actually abandoned by everybody, the church, the community, their families. Most of them were really poor. They weren’t living on the street, but they were living in dysfunctional homes. It’s the same thing.

Anyway, they were kids and the reason that body of work has survived is that it’s about emotion. That kind of mood and tension and sexual vitality, that’s what those pictures were really about. They weren’t about war. I mean, you can’t compare those kids to the kids today who have machine guns. So there is an innocence in the photographs because it reflected the kids’ innocence, but that innocence could erupt into violence. It’s interesting that the leader of the Brooklyn Gang, Bengie, who is now 65 years old, called when I was given a large show of the Brooklyn Gang at the International Center for Photography (ICP) in New York in 1998–99. My wife and I went down together and had coffee with him in midtown, and he turned out to have had an extraordinary life. He is now a substance abuse counselor. We just returned last Sunday from his birthday party, where we saw some of the old gang members.

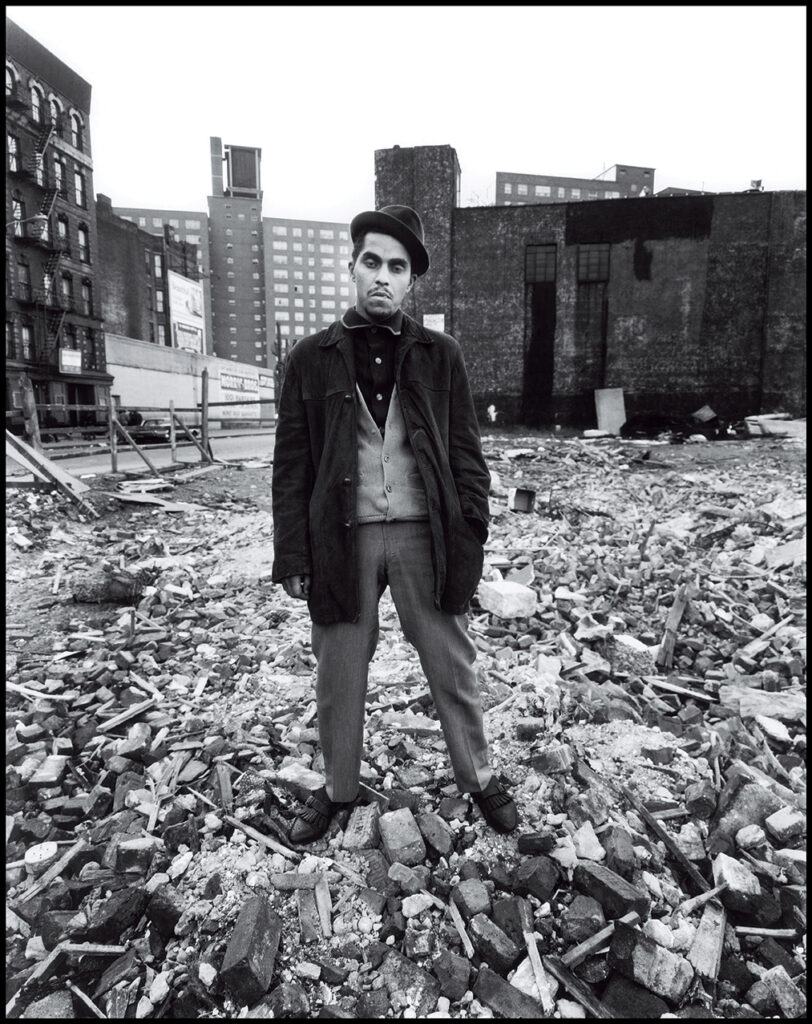

Perhaps we could discuss East 100th Street for a while. You photographed on that block from 1966 to 1968. The book East 100th Street was published by Harvard University Press in 1970, and was reissued in an expanded edition by St. Ann’s Press in 2003. You received the first-ever photography grant from the National Endowment of the Arts in 1966, which you used in support of the East 100th Street project. East 100th Street appeared as a solo exhibition — your second at this venue — at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1970. How did you come to be introduced to the people on East 100th Street?

Sam Holmes, the picture librarian at Magnum who told me about the circus in Palisades Amusement Park, also told me about the “worst block in Spanish Harlem.” His cousin was a minister living on the block and working with the Metro North Citizens’ Committee. So I looked up the minister and had an appointment with the Citizens’ Committee and then I photographed for two years.

Were you attempting to create collaboration between the photographer and the subject?

Yes, one of the reasons I chose to use what would be regarded as an old-fashioned view camera on a tripod, with a flash, was that I felt it dignified the act of photography. I was eye-to-eye, face-to-face with the subject. The only thing that connected me to a camera was the little cable release, but I was really looking into the eyes of my subject. The environment was also important; what surrounded them was part of the picture, too. It was part of their expression. If the wall had a picture on it or a birdcage or nothing, it said something about them.

In some of the photographs the people presented themselves in a middle class way, very dressed up. Why do you think they chose to do that?

Well, you know, people are middle class in their minds. They may not own an automobile, but they dress very elegantly on Sunday, going to church. I had an experience in which I saw some children half-naked. They just had some little panties on and they were playing on the fire escape.

I went to take that picture. The mother saw me and brought the kids in through the window. I counted the floors and went up and knocked on the door. The woman said, “You can photograph my children that way, but you must also photograph them dressed up.” So I photographed them playing on the fire escape and on Sunday I photographed the family dressed up.

Much has been made of the dark tonality of the photographs in East 100th Street. Did that tonality emerge immediately as your intention, or did it evolve over time?

When I entered a person’s home I was entering a sacred space, is the way I looked at it. It was up to the person to decide where the photograph might be made. Was it in the kitchen, in the bedroom, or in the vacant lot downstairs? Most of the time it was in the bedroom because it was a quiet space and it had artifacts or clues to their spirituality, like a cross, a picture of Jesus, a framed photograph of John F. Kennedy.

Very often these dwellings were dark. I remember a photograph I took of an elderly woman sitting on a bed with towels and rags stuck into the cracks in the window to keep out the cold air. That was an important part of the photograph, which showed her sitting alone in this dark room with only one little light bulb on the ceiling. I tried to be true to the mood, to the darkness, and through the darkness I made a light because I made an image of that person’s predicament in life. So when I printed the photographs for the book I printed them in a very strong and heavy way. In fact, I was inspired by the bronze Degas sculpture of dancers at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The bronze looked like shrapnel to me. It was dark, metallic, rich, and I followed that through as a theme in the printing of my photographs. I was highly impassioned in those days with that tonality.

Years later, when I was printing for the second edition of East 100th Street, I opened up the tonality because I was able to: the technology had improved. I had the aid of a scanner. I made the printing a little lighter. East 100th Street wasn’t just a documentation. It was a vision, a vision in which I reached into the tonality with a large format camera. I wanted that depth of field. I wanted to be able to see down to the street while someone was lying on the couch. The way the camera was used, the way the lighting was used, the way I saw things were all part of the aesthetic. The aesthetic dimension to East 100th Street combined with the sociological message.

How recently have you had contact with the people on the block?

A few years ago I received a fellowship from the Open Society to go back to photograph. When I returned I could find very few people I knew. They had moved on. You know, people move on. What happened in the 1960s was that a matrix of new schools, tutorial programs, all kinds of things, rippled all through Spanish Harlem. Metro North Association was the beginning of that self-improvement, reviving the community. The community itself was doing it. I photographed positive aspects of new schools, new housing, tutorial programs, a new park and ball field, a women’s health center, the vest pocket gardens, and the new mood and the street. I’ve donated all that work to the Union Settlement and it is on display there. Yes, Spanish Harlem has changed. It’s almost easier to get a caffe latte now than a café con leche. Some of the texture is lost, but it’s a lot safer than it was.

Obviously you maintain contact with people you have photographed over the years. Can you tell us more about that?

I do, but I don’t overdo it, because life goes on. In Time of Change, there is a picture of a woman in a shack holding a baby, made during the Selma march. I found that baby and I found the whole family recently and re-photographed them.

Their lives had changed tremendously because of the Voting Rights Act that allowed the younger children to get a better education. One of the 11 children holds a master’s degree in library science and became head legal librarian at the State Capitol in Montgomery, Alabama. Almost all of the younger children I photographed have successful lives.

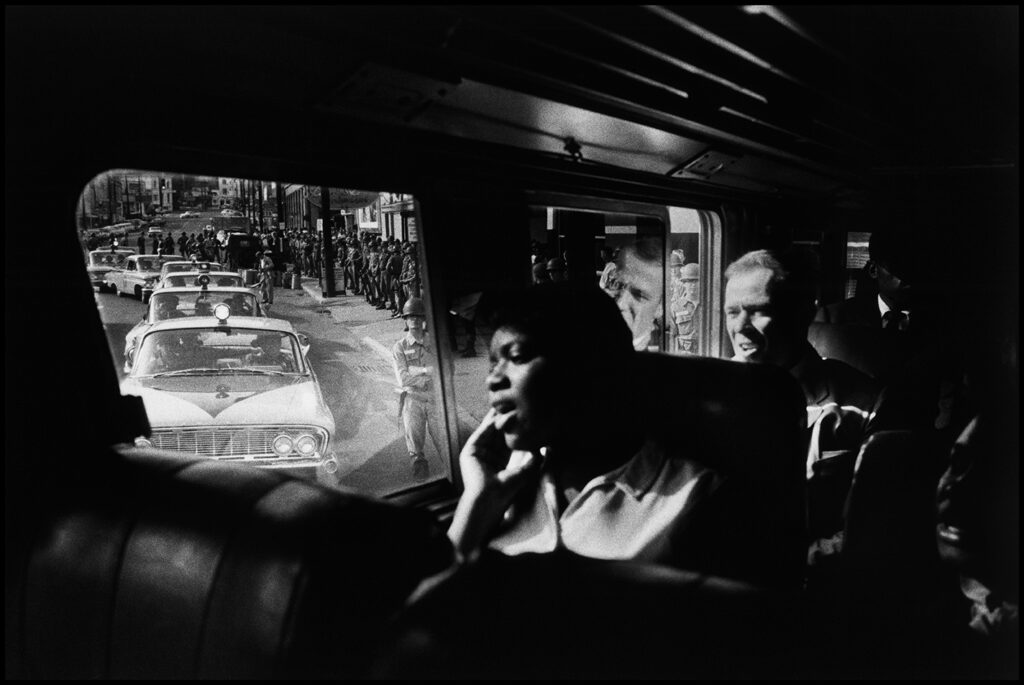

You photographed the Civil Rights Movement, primarily in the American South, from 1961 to 1965. In 1962 you received a Guggenheim Fellowship in support of this project, and in 1963 the Museum of Modern Art included these historic images, among others, in a solo exhibition. The book, Time of Change, Civil Rights Photographs 1961–1965 was published by St. Ann’s Press in 2002. In that same year, the International Center for Photography presented an exhibition of Time of Change. When you were photographing these events in the early ’60s, did you find it a frightening experience?

Oh, yes, because if you made a mistake and you got into a situation that you couldn’t get out of…that almost happened to me. I photographed a Ku Klux Klan meeting, but I drove my little Volkswagen bug too close to the cross.

When they lit it, they said, “New York license plate so-and-so, you’re too close to the fire.” I knew that that was not going to be cool, to have New York license plates at a Klan meeting in Georgia. I stayed a while, took a few pictures, and then left.

Would you call the Civil Rights photographs a turning point in your life?

Well, it certainly made it possible for me to understand what I was getting into in East 100th Street. It was the prelude to East 100th Street. It was like my homework. I had borne witness to what was going on in the South and to some extent become sensitized to what was happening in the North, too. Without that background I don’t think I would have done East 100th Street the way I did.

What about your early fashion days? How did that happen?

The story I heard was that after Brooklyn Gang was published, Alex Lieberman, the creative director of Vogue Magazine, was having lunch with Cartier-Bresson. He asked Bresson if he thought the young Bruce Davidson could do fashion. Bresson’s answer was: “If he can do gangs, why can’t he do fashion? What’s the difference?”

So I did a lot of fashion for about three years. I rarely do fashion now. I came to a point in the Civil Rights Movement where I was doing fashion and also protest marches and I couldn’t equate the two things, so I gave up fashion. I’m good at fashion photography but it doesn’t give me meaning. It’s like cotton candy. It looks beautiful, but it melts in your mouth, and the sugar can rot your teeth.

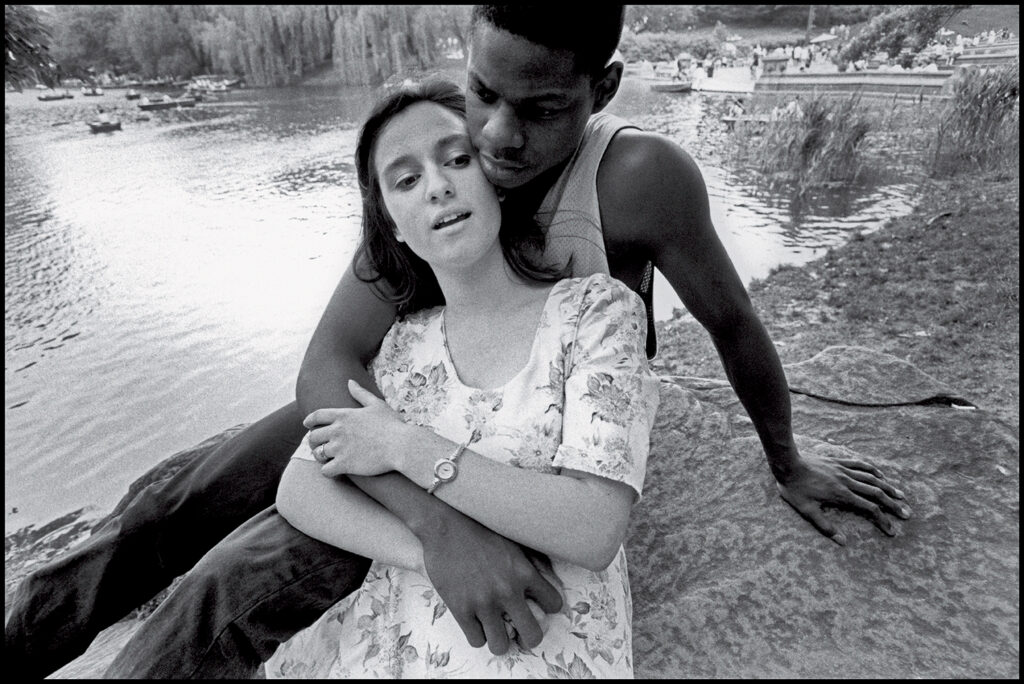

During the early 1990s, you did an extensive series on Central Park here in New York, which culminated in the book Central Park, published by Aperture Press in 1995. How did that series come about?

I did a body of work for National Geographic Magazine called The Neighborhood, in which I retraced my boyhood steps in the Chicago area. After I completed that the editors asked me what else I would like to do. I said I’ll make a list of ten things. To make it an even ten, I added Central Park. We used to take the kids there and at that time it was like a dust bowl. You never knew when you were sitting with your children if there were hypodermic needles sticking them.

Then the editors said, “Oh, Central Park, that’s a good idea.” I said, “I need four seasons and I need to be in black-and-white.” They said, “Oh, no, we are a color magazine. You have to do it in color and we can give you only three seasons.” So I went out and I started photographing Central Park. I exposed 500 rolls of film. Then we had a presentation. The next morning I got a call from the editor-in-chief Bill Graves, who said, “We’re pulling the plug on this project. Think of something else.” So I said to myself, “Good, I’m free at last,” and I went back to Central Park with my Canon Cameras and I spent the next three years photographing in black-and-white.

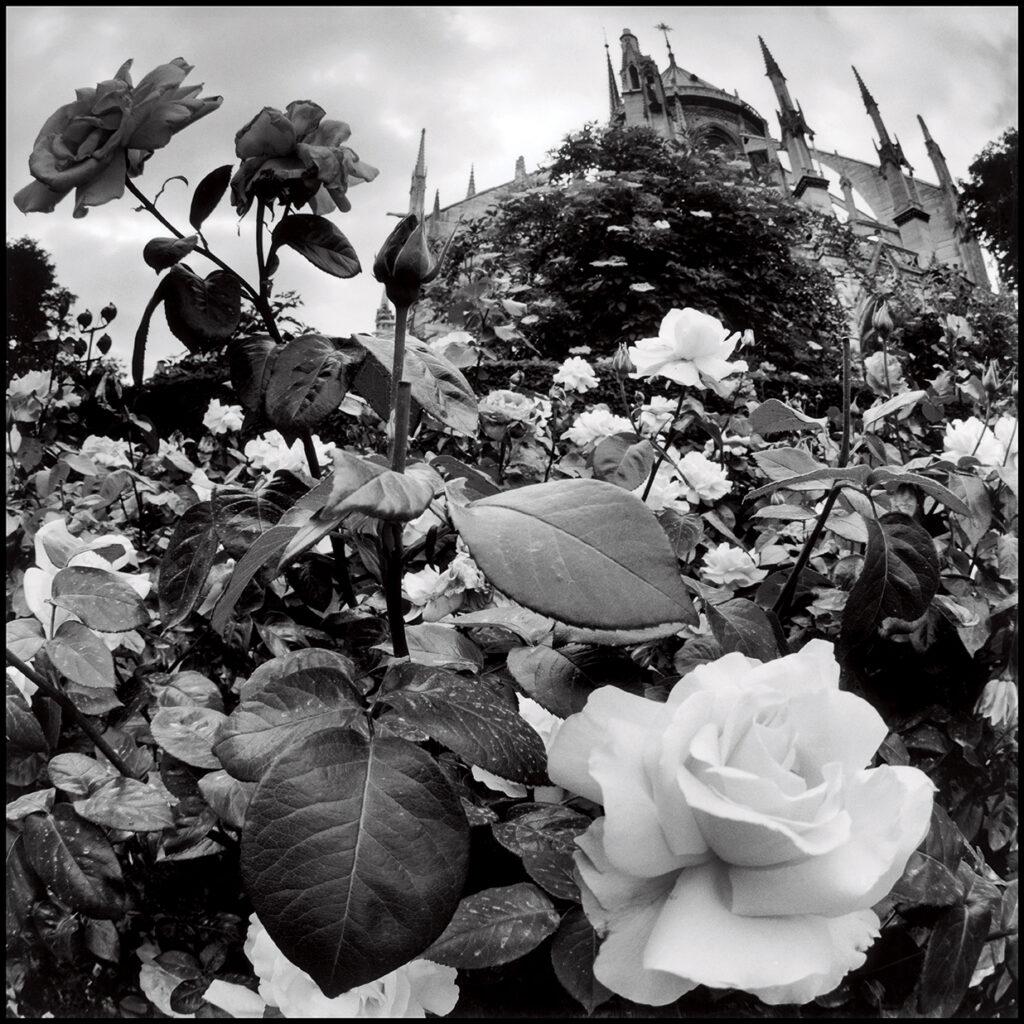

What are you interested in photographing at present?

I’m interested in the balance of nature right now and the meaning of the vegetation that at times goes unnoticed in our lives. I just finished a large body of work called the Nature of Paris. It was shown at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris.

The exhibition opened in June of 2007 and closed in September. In Paris I think I made an homage to vegetation. In that city the monuments take over. We go to the Eiffel Tower and we don’t realize there’s a 500-year-old tree growing right next to it. When you see the pictures it will be self-evident. I’m interested in raising people’s consciousness, my own included, to the meaning and the need for green space and vegetation. When I began the project in Paris, I began by photographing some people in nature. For instance, my assistant found an elderly woman in the cemetery in Montmartre, a woman well into her 80s or 90s. There were cats standing on the tombstones, waiting for her to come to them with food. They wouldn’t just rush in. I photographed her and also lovers in the park and all that kind of stuff, and I was getting sick from it. I edited it all out, including the panoramas, even though the panoramas were successful, I thought. I edited all the 35mm pictures out. There was something I was doing with the square format that was coming through to me. In the end the whole show was nothing but the Hasselblad 2 ¼” photographs. I was able to disinvest all that other imagery, which I’d already done, into something that I hadn’t done, something that was new to me, fresh to me. And challenging. I’m looking for another city that would be the extension of Central Park and Nature of Paris. I would like to continue the concept that was born through the Paris photographs.

At what point did you become interested in selling your photographic prints through galleries?

I was too busy photographing during the 1970s to become affiliated with a gallery. I became interested in the 1980s. It was Howard Greenberg who really brought me out of the fine art world “shadows” and into the sunshine. I had my first exhibition with his gallery in New York in 2002. I felt that Howard could really embrace my work and he did. Howard is, as they say in Yiddish, meshpokha, he’s family.

He understands the work, he’s honest, he’s energetic, and he assigned me Nancy Lieberman, who is wonderful, and who manages my work for the gallery. Recently she arranged for my wife and me to go to Greece for a 75-print commemorative exhibition for the Hellenic-American Institute in Athens.

Sandra Berler in Chevy Chase, Maryland is my sister-in-law and has represented me and others for over thirty-five years. In addition to owning a fine gallery, she is an excellent art historian and writer. Recently she arranged a show of my work along with a lecture at Sidwell Friends, the well-known school in Washington, D.C. This was a very successful experience.

On the West Coast, Rose Shoshana and Laura Peterson of the Rose Gallery have mounted some of the most beautiful exhibitions I’ve ever had. They did a dye transfer color show of Subway that was amazing to see, and before that, Brooklyn Gang. They had a patron who underwrote the creation of a portfolio of Subway containing 47 very large dye transfer prints (20 x 24″) in an edition of 7. I think there are only two portfolios left.

I am now working with three people: Howard Greenberg Gallery, in New York, Rose Gallery in Santa Monica, California and the Sandra Berler Gallery in Chevy Chase, Maryland.

After 9/11, did you have a desire to photograph events here in New York City?

Well, I went down a night or two to 9/11 to photograph. It was very difficult to get permission to work. I had sent a whole portfolio of photographs — not of 9/11 — to Hillary Clinton, but it never got to her.

The FBI just X-rayed things and kept them, so I got those prints back a year later. So I didn’t have permission to get down there, but I knew someone who operated a building nearby and they were housing police overnight. He said the captain would be willing to take me around for a while at night, but that was all I could get.

In my slide presentation I have a photograph of the Twin Towers at night with the Statue of Liberty before 9/11. It’s a photograph that can be taken only with a 1700mm telephoto lens. There are only two in the world. I borrowed it from Canon. My wife did the scouting. She found a pier that jutted out a quarter of a mile into the bay.

It’s a Kodachrome picture of the World Trade Center at night, lit by the office lights in the windows. When I took it I thought, oh, yeah, this is a perfect symbol of consumerism, materialism, all of that. But after 9/11 it became a memorial image, like two candles set on the altar of life and death. Esquire Magazine gave me an assignment to photograph some aspect of America after 9/11. I just didn’t feel comfortable going someplace like the Grand Canyon, so I went to Katz’s Delicatessen. I spent a month at Katz’s making photographs of people eating pastrami, because I wrote, “Pastrami and Peace Go Together.” You feel very peaceful when you are digesting pastrami. I felt that freedom was about being able to photograph the impossible or the vulgar or whatever, or simply people enjoying themselves.

What projects are you involved with at present?

I still do some editorial photography. In fact, I just did a really interesting project with CareOregon, a private healthcare company that asked me to photograph a number of their members. These are people who are very, very sick. They are in their homes, not in the hospital. CareOregon made two beautiful exhibitions of the work, one at their headquarters in Portland and one in the Department of Human Services Building in Salem. Legislators got the chance to see people who really need care, and who are having good care right now through CareOregon. There were testimonials that were heart-wrenching.

You’ve mentioned in interviews being influenced by W. Eugene Smith and Robert Frank and have said, “Cartier-Bresson was Bach, Smith was Beethoven, and Frank was Claude Debussy. They’re all in my DNA.”

Well, definitely Smith was an influence because his photographic essays published in Life were very powerful. To some extent I was influenced by Robert Frank, but I moved away from him completely when I did East 100th Street.

Do you have any final statements to make about your work?

I would say I work out of a state of mind. When I’m photographing the dwarf in the circus, I’m confronting myself as a giant compared to this dwarf, but I’m not a giant compared to other people who might be a foot taller than I am.

So then I confront another reality; I’m in another state of mind. Even in the Civil Rights Movement I’m erasing my own heritage and the town I grew up in. We didn’t have any social experience with black people at all. So I’m learning about that oppression as I go deeper into the Civil Rights Movement. And East 100th Street is another frame of mind. Then I work on that. I don’t read an article in The New York Times and think, well, that’s a good idea, I’ll work on that. No, my work is very personal. It’s a personal barometer of my life, a voyage of consciousness that is my life’s work. Each one is different. My wife says, “You always start with zero, you erase your clichés,” as I did in Paris. You’re only seeing what I ended with, what I felt the thing is. So there’s a psychological, there’s a visual, there’s a contemporary, there’s an artistic element. I, personally, have been printing my body of work during January and February for the last two or three years, and I’ve accumulated about 1,200 prints in that time. I’m doing it because it needs to be done. One of my publishers, Gerhard Steidl, who does beautiful, highest-quality work, and who published England/Scotland 1960 in 2005 and Circus in 2007, is talking about publishing a four or five volume set of books of my life’s work. That would be great, if it happens. I would also like to give my wife Emily credit for her keen intelligence, visual acuity and inspiration through all these years that we have lived and worked and raised our children together.

Jain Kelly was the assistant director of The Witkin Gallery in New York City from 1971-78. She has written numerous articles on various aspects of photography and is a fine-art photography consultant to collectors. Her email is [email protected].

]]>Lawrence Schiller was one of those photographers whose name may have been forgotten, but whose photographs have not. Beginning last year a touring exhibition of his work has been drawing very large audiences in Beijing, Hong Kong, Salzburg, Berlin, London, and Sofia, Bulgaria. Indeed, in Bulgaria over 16,000 people lined up to see Marilyn Monroe and America in the 1960s, a paid-admission exhibition.

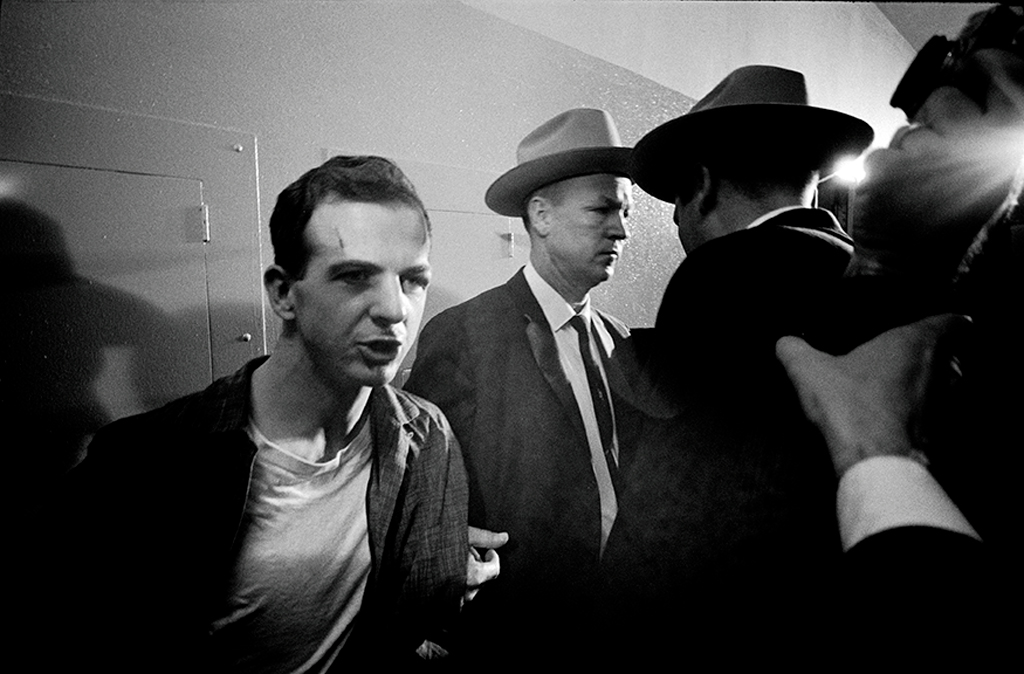

What could account for such an astounding turnout even for photographs of Marilyn? Schiller — as amazed as anyone else — wanted to know, and so he conducted a survey during the last 60 days of the show’s run to find out. “The response was very interesting,” says Schiller. “The demographics said they knew about the events in America in the ’60s, but had never seen images of them. They’d heard of [LSD guru] Timothy Leary, but [had] never seen a photo. [JFK assassin Lee Harvey] Oswald, but not a photo. The socialist government had controlled the media in those years. Same in China. They’d never seen that image of Oswald’s gun. They’d heard about the acid generation, but had never seen photos of [On The Road author] Jack Kerouac and people like that. So [the exhibition] wound up being bigger than we’d ever imagined.”

And the success Schiller’s images are enjoying with collectors matches the success the exhibition has enjoyed with the public. The relationship isn’t accidental. Schiller had commercial success in mind from the beginning. Schooled in business by his father from an early age (“I was behind the retail counter from the time I was maybe 9 or 10 years old”), Schiller could always see how to turn photographs into money, “and that may have worked against me being a photographer,” he says. Certainly, it set the stage for some criticism over the years from fellow photographers less commercially minded (and thus less commercially successful) than Schiller.

A little criticism hasn’t stopped or even slowed Schiller in a career that began in photojournalism but evolved into producing and directing motion pictures for television (five Emmy-winning) and writing and publishing many well-known best sellers (American Tragedy, on the O. J. Simpson trial, and Perfect Murder, Perfect Town, on the Jon-Benet Ramsey case). Along this colorful path, Schiller’s knack for making connections and making deals also ended up rescuing W. Eugene Smith, one of the least commercially minded photographers of that era, from a hospital in Japan and making the deal that finally brought Smith’s classic Minamata (1973) into print.

Schiller led such a varied, interesting, and successful life as a photojournalist, it’s hard to know where to start in filling in the background. Jacob Deschin called him “a pro at sixteen” in US Camera back in 1953 when Schiller was still in high school. He was winning awards right and left. He wrote a chapter on lighting for the Graphic-Graflex Photography book, had photos published in The Saturday Evening Post and LIFE, and shot his first playmate for Playboy in 1958. (He would, incidentally, go on to photograph Paula Kelly for Playboy in 1969, the first playmate to have her pubic hair escape the previously ubiquitous editorial airbrush.) Schiller’s photo of Nixon losing to John F. Kennedy won the National Press Photographers Association “Best Storytelling Photo” award in 1961. Two years later, it would be his photo of a Dallas policeman holding Lee Harvey Oswald’s rifle above his head in a media-crowded hallway that would forever nail that moment from that awful time in the minds and memories of millions.