To be there at the door of history, to know what it is like to live fully in one’s time and within the moment that is given, to know the direction of the blowing wind and to catch it and ride it. Margaret Bourke-White was bombed and survived, was strafed and survived, was torpedoed and survived, and she fell from the sky in a helicopter and survived. She dared high places—along the face of the new Chrysler Building in New York City, for instance—and she acted as one with the lowly and looked death in the eye. And when her own time came early, at 67, she died in a home where her wall displayed a poster-sized image of the trees she had photographed in Czechoslovakia.

Maggie the Indestructible began her serious work in photography with Clarence White, one of artists who led the process of defining a beautiful photograph early in the 20th century, and who established a school in his name, associated with Columbia University, where, in 1922, Bourke-White had enrolled as an undergraduate to study biology. Her elective study with White formed a strong orientation to the compositional priorities of Pictorialism, and she continued to fill the frame of her image with clarity and strength. That was her skill— filling up the frame, grandly, leaving little for guesswork.

After college (she graduated from Cornell University in 1927) her soft focus crystallized to a modernist’s hard edge. She found a subject in the musculature of the heavy industry in the Cleveland area. “A dynamo is as beautiful as a vase,” she said. And while her work followed the rhetorical lessons of Pictorialism, such as with the effective use of repetition in Hydro Generators, Niagara Falls Power Company and Fort Peck Dam (the cover image from that first Life magazine, November 23, 1936), it became something else. Yes, she took the lesson from Arthur Wesley Dow, the early 20th century critic and lecturer she heard at Columbia, who argued for the dramatic effect of a slice of light or rake of shadow. This affect appears dramatically in Romance of Steel, with a title still clinging to the connotations of a previous era. The image won first prize in the 1930 Cleveland Museum of Art regional exhibition. But Bourke-White’s sympathies were elsewhere—no longer with the connotations of soft focus. Her lens looked hard at just what was out there. New technologies had grown up in this fast changing 20th century. Her photographs carried the banner of change, and the tough mind and hopeful spirit of a New Deal.

She quickly rose in opportunity and fame, as Henry R. Luce’s favorite photographer. He discovered her and in 1929, brought her on for Fortune, his new magazine, and for its first year, she was the magazine’s only photographer. Then in 1936, Luce brought her over to his new Life. Bourke-White was confident, tough and smart. She got it done, and usually better than expected. That first cover, assigned to reveal the largest earthen dam in America, developed in her eye as a story about the new life on the frontier, now on the shoulders of technology rather than cattle, not simply a story about a big public work. She had covered the industrial development of Russia and had been the first outsider to gain permission there. She knew what she was doing, and how to look around corners for the full story. Her powerfully designed, bold-yet-simple compositions captured the Soviet’s sense of themselves as an emerging power. Then she photographed the Dust Bowl in the Midwest and sharecroppers in the South. She worked with the novelist Erskine Caldwell, later her husband of three years (1939–42). Their fine book together, You Have Seen Their Faces, about the Depression South, is not sufficiently recognized. If it takes liberties with quotations, it remains assertively true to the facts of the matter of poverty, and it effected significant social change.

When she had the chance, she took the liberty to pose and design a shot; she was notorious for packing hundreds of pounds of gear, including multiple flash setups that she employed to render the dark insides of industrial sites that attracted her. She overshot and counted on her assistants back at Life, a staff the envy of her colleagues, to process and print, when feasible, to her specifications.

Her work, almost always made for publication, is rarely signed. Of the 335 images (and 75 contact sheets) by Bourke-White in the George Eastman House collection, only three are signed, “Bourke White” on two lines, with a great flourishing “W”, though she also signed her full name more modestly, too. Two of the images are signed on the mount in the lower right, and one on the print in the lower left. The remainder is stamped by her—“A Margaret Bourke-White Photograph”—with the stamp or copyright of the originating publication.

She also published with The New York Times Magazine and the short-lived liberal newspaper without ads, PM. Finally, she created several portfolios—one with Time-Life just before she died, another about Russia in the early ’30s. Bourke-White was first in line to cover the Second World War in North Africa and in Europe, following General Patton into Germany and documenting the concentration camp horrors of Buchenwald upon cease-fire. “Nothing attracts me like a closed door,” she said in her autobiography, Portrait of Myself in 1963.

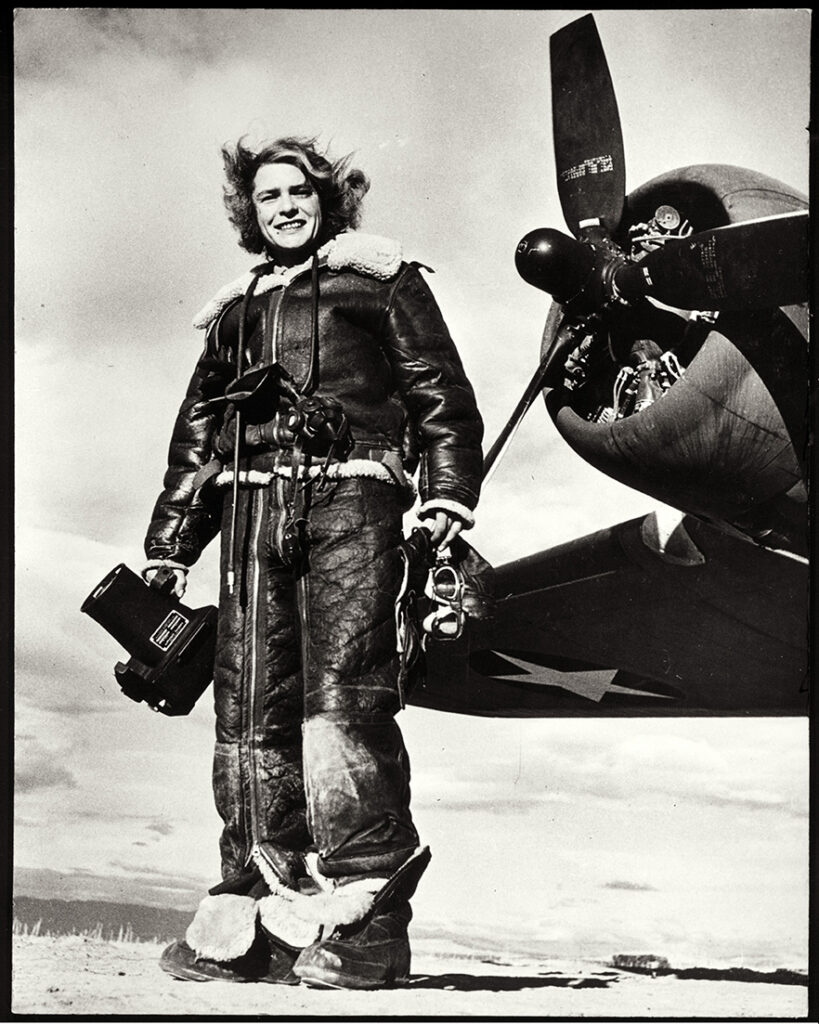

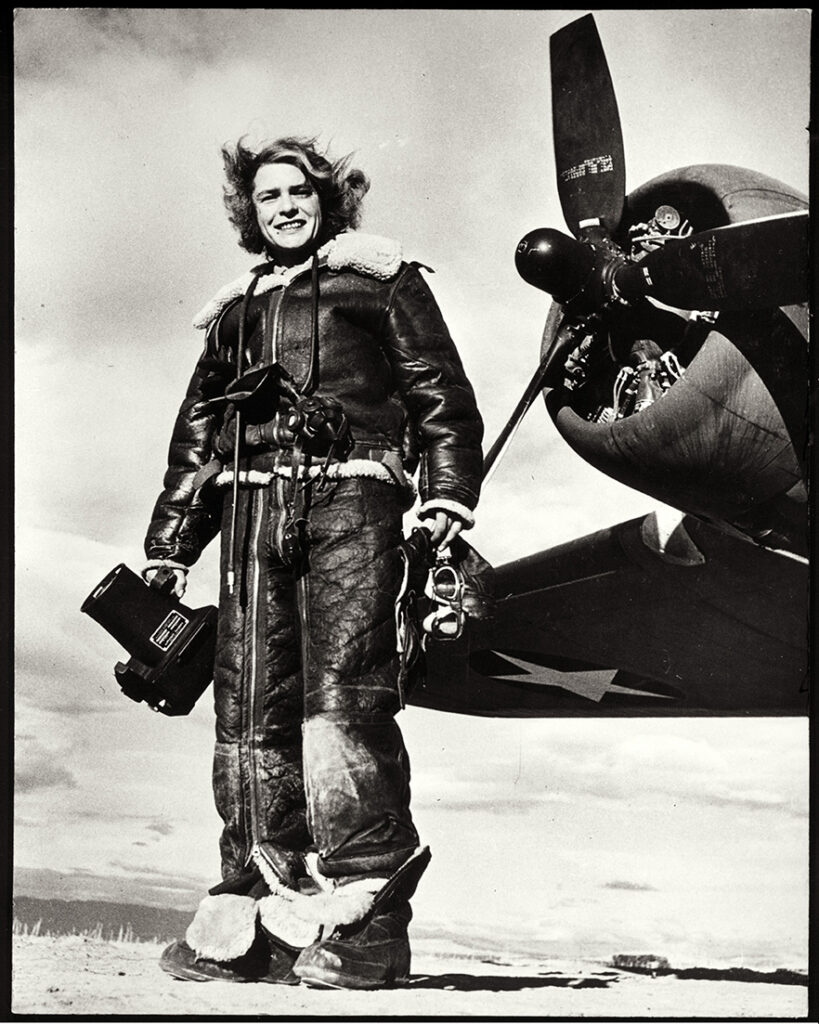

The late Jack Naylor, a pilot during the war who became a prominent collector of photographs and photo technology, remembered clicking the shutter of her camera for her breezy self-portrait in front of his plane. He would take her on reconnaissance flights and into combat, and recalled her fearlessness and fierce determination to get the image. After the War, she continued to report on the conflicts in India over partition with Pakistan, and on labor conditions in the mines in South Africa; and later on, the guerilla conflicts after ceasefire in Korea. Only the development of Parkinson’s disease slowed her and eventually brought her career with Life to a halt in 1957. She died in 1971.

George Eastman House has all of her books and those about her. Time-Life Picture Collection in New York preserves her negatives. The largest collection of her work is held by Syracuse University. Other large collections are held in the Cleveland Public Library, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the Library of Congress and the Museum of Modern Art. In two separate books, Vicki Goldberg and Sean Callahan write well about her life. Farrah Fawcett portrayed her in a 1989 television movie, Double Exposure, and Candice Bergen portrayed her in the 1982 theatrical release, Gandhi. John Szarkowski, writing on his appreciation of the collection he curated at the Museum of Modern Art, termed her “one of the most famous and most successful photographers of her time,” praising “her combination of intelligence, talent, ambition and flexibility….” Said Bourke-White, “Work is something you can count on, a trusted lifelong friend, who never deserts you.”

Anthony Bannon is the seventh director of George Eastman House, the International Museum of Photography and Film in Rochester, New York.

]]>GORDON PARKS: A CHOICE OF WEAPONS

NEW YORK CITY—Howard Greenberg Gallery will present the photography exhibition Gordon Parks: A Choice of Weapons from October 8 through December 22 in the new gallery on the 8th floor of the Fuller Building at 41 East 57th Street.

One of the world’s leading galleries for classic and modern photography, the Howard Greenberg Gallery is celebrating its 40th anniversary with an exhibition of important work by the renowned photographer and filmmaker Gordon Parks. Through his still images, both candid and staged, the exhibition explores the roots of Parks’ future as a filmmaker.

Parks, who described his camera as his “choice of weapons,” was known for his work documenting American life and culture with a focus on social justice, race relations, the civil rights movement, and the African American experience. He was hired as staff photographer for Life magazine in 1948, where over two decades he created some of his most groundbreaking work that cast light on the social and economic impact of poverty, discrimination, and racism.

In 1969, Parks launched a pioneering film career by becoming the first African American to write and direct a major studio feature, The Learning Tree, based on his semi-autobiographical novel—a career move foreshadowed through his cinematic approach to photography.

Marking the 50th anniversary of the release of Parks’ second feature-length directorial endeavor, Shaft (1971), a classic New York City detective film that spawned the blaxploitation genre, the gallery will present photographic works that reveal the artist’s cinematic approach.

Parks’ earliest photographs often imply a narrative beyond the individual frame, echoing his desire to represent complex facets of his subjects’ lives and communities. Like his films, Parks’ photographs present robust narratives that seek to reveal the complexities of his subjects’ lives.

The works on view include those staged in 1952 in collaboration with Ralph Ellison and inspired by his novel Invisible Man, as well as those made while Parks was embedded with the New York gang leader “Red” Jackson in 1948, and images of the Fontenelles, a Harlem family that struggled to feed their eight children in 1967.

The exhibition coincides with the release of the HBO documentary A Choice of Weapons: Inspired by Gordon Parks in November, and the extended presentation of works from his series The Atmosphere of Crime in the permanent collection galleries of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

About Gordon Parks (1912-2006)

Gordon Parks was born into poverty and segregation on a farm in Kansas in 1912, the youngest of 15 children. He worked at odd jobs before buying a camera at a pawnshop in 1938 and training himself to become a photographer. From 1941 to 1945, Parks was a photographer for the Farm Security Administration and later at the Office of War Information in Washington, D.C. As a freelance photographer, his 1948 photo essay on the life of a Harlem gang leader, Red Jackson, won him widespread acclaim and a position as the first African American staff photographer and writer for Life magazine, which continued until 1972. In addition to being a noted composer and author, in 1969, Parks became the first African American to write and direct a Hollywood feature film, The Learning Tree, based on his bestselling novel of the same name. This was followed in 1971 by the hugely successful motion picture Shaft. Parks was the recipient of numerous awards, including the National Medal of Arts in 1988, and was given over 50 honorary doctorates from colleges across the United States. Photographs by Parks are in the collections of many major museums, including the Museum of Modern Art, J. Paul Getty Museum, National Gallery of Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Harvard Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. stated, “Gordon Parks is the most important Black photographer in the history of photojournalism. Long after the events that he photographed have been forgotten, his images will remain with us, testaments to the genius of his art, transcending time, place and subject matter.”

About The Gordon Parks Foundation

The Gordon Parks Foundation permanently preserves the work of Gordon Parks, makes it available to the public through exhibitions, books, and electronic media, and supports artistic and educational activities that advance what Gordon described as “the common search for a better life and a better world.” The Foundation is a division of the Meserve-Kunhardt Foundation.

About Howard Greenberg Gallery Since its inception in New York 40 years ago, Howard Greenberg Gallery has built a vast and ever-changing collection of some of the most important photographs in the medium. The Gallery’s collection acts as a living history of photography, offering genres and styles from Pictorialism to Modernism, in addition to contemporary photography and images conceived for industry, advertising, and fashion. Formerly a photographer and founder of The Center for Photography in Woodstock in 1977, Howard Greenberg has been one of a small group of gallerists, curators and historians responsible for the creation and development of the modern market for photography. Howard Greenberg Gallery—founded in 1981 and originally known as Photofind—was the first to consistently exhibit photojournalism and ‘street’ photography, now accepted as important components of photographic art.

The Gallery is located in two 57th Street locations: an exhibition space on the 8th floor of the Fuller Building at 41 East 57th Street; and an entire floor at 32 East 57th Street, directly across from the Fuller Building, to house, manage and present its vast archive of over 40,000 prints.

For more information, contact 212-334-0010, [email protected] or visit www.howardgreenberg.com.

]]>