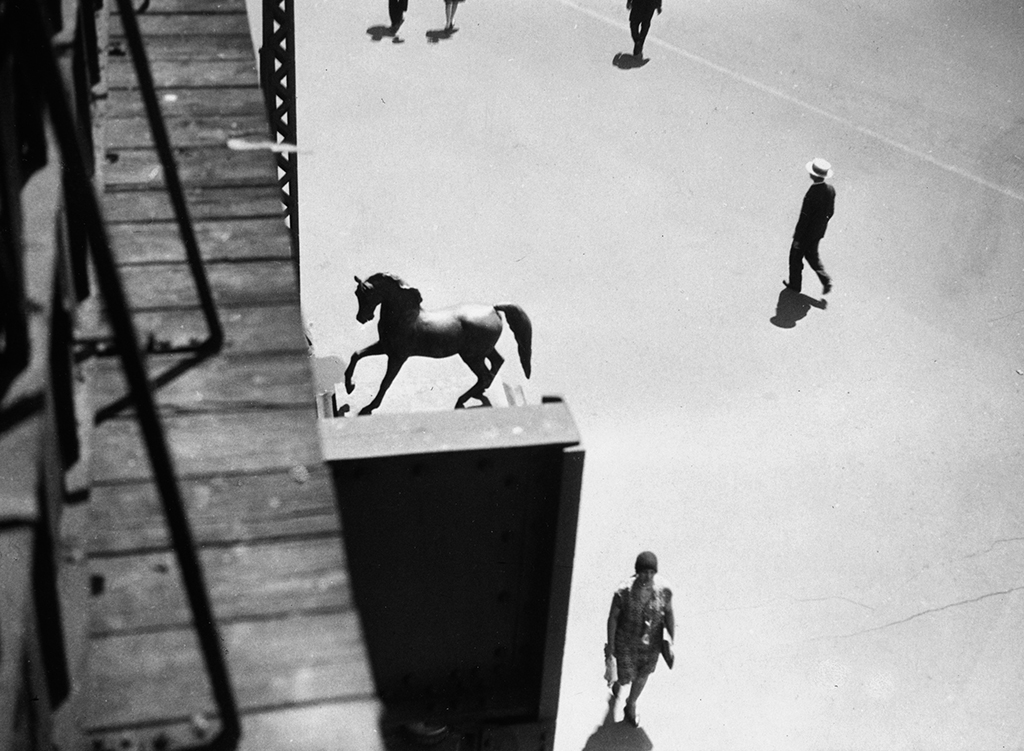

One of the world’s leading galleries for classic and modern photography, the Howard Greenberg Gallery is celebrating its 40th anniversary with an exhibition of important work by the renowned photographer and filmmaker Gordon Parks. Through his still images, both candid and staged, the exhibition explores the roots of Parks’ future as a filmmaker.

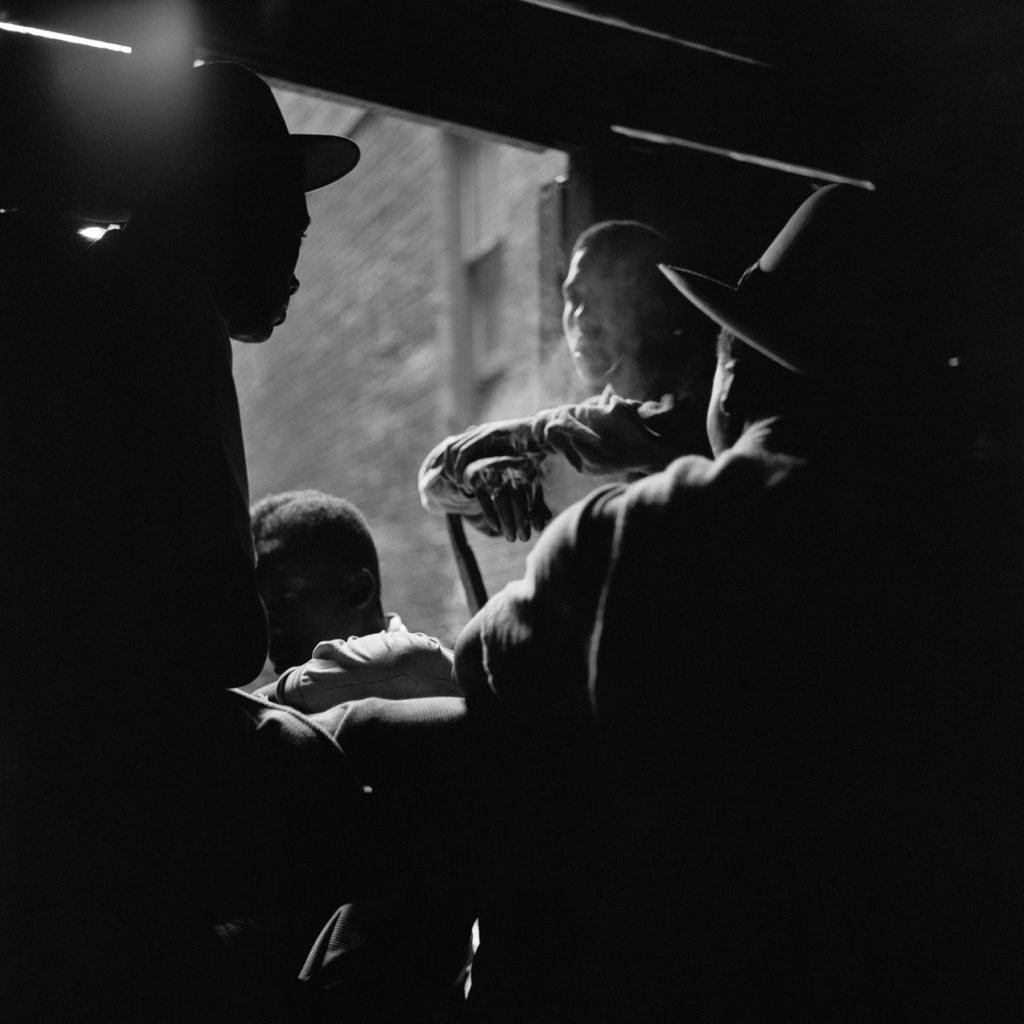

Parks, who described his camera as his “choice of weapons,” was known for his work documenting American life and culture with a focus on social justice, race relations, the civil rights movement, and the African American experience. He was hired as staff photographer for Life magazine in 1948, where over two decades he created some of his most groundbreaking work that cast light on the social and economic impact of poverty, discrimination, and racism.

In 1969, Parks launched a pioneering film career by becoming the first African American to write and direct a major studio feature, The Learning Tree, based on his semi-autobiographical novel—a career move foreshadowed through his cinematic approach to photography.

Marking the 50th anniversary of the release of Parks’ second feature-length directorial endeavor, Shaft (1971), a classic New York City detective film that spawned the blaxploitation genre, the gallery will present photographic works that reveal the artist’s cinematic approach.

Parks’ earliest photographs often imply a narrative beyond the individual frame, echoing his desire to represent complex facets of his subjects’ lives and communities. Like his films, Parks’ photographs present robust narratives that seek to reveal the complexities of his subjects’ lives.

The works on view include those staged in 1952 in collaboration with Ralph Ellison and inspired by his novel Invisible Man, as well as those made while Parks was embedded with the New York gang leader “Red” Jackson in 1948, and images of the Fontenelles, a Harlem family that struggled to feed their eight children in 1967.

The exhibition coincides with the release of the HBO documentary A Choice of Weapons: Inspired by Gordon Parks in November, and the extended presentation of works from his series The Atmosphere of Crime in the permanent collection galleries of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

About Gordon Parks (1912-2006)

Gordon Parks was born into poverty and segregation on a farm in Kansas in 1912, the youngest of 15 children. He worked at odd jobs before buying a camera at a pawnshop in 1938 and training himself to become a photographer. From 1941 to 1945, Parks was a photographer for the Farm Security Administration and later at the Office of War Information in Washington, D.C. As a freelance photographer, his 1948 photo essay on the life of a Harlem gang leader, Red Jackson, won him widespread acclaim and a position as the first African American staff photographer and writer for Life magazine, which continued until 1972. In addition to being a noted composer and author, in 1969, Parks became the first African American to write and direct a Hollywood feature film, The Learning Tree, based on his bestselling novel of the same name. This was followed in 1971 by the hugely successful motion picture Shaft. Parks was the recipient of numerous awards, including the National Medal of Arts in 1988, and was given over 50 honorary doctorates from colleges across the United States. Photographs by Parks are in the collections of many major museums, including the Museum of Modern Art, J. Paul Getty Museum, National Gallery of Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Harvard Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. stated, “Gordon Parks is the most important Black photographer in the history of photojournalism. Long after the events that he photographed have been forgotten, his images will remain with us, testaments to the genius of his art, transcending time, place and subject matter.”

About The Gordon Parks Foundation

The Gordon Parks Foundation permanently preserves the work of Gordon Parks, makes it available to the public through exhibitions, books, and electronic media, and supports artistic and educational activities that advance what Gordon described as “the common search for a better life and a better world.” The Foundation is a division of the Meserve-Kunhardt Foundation.

Paris Photo, the world’s leading art fair dedicated to photography, returns for the 24th time with a packed schedule at the impressive Grand Palais Ephémère in the heart of the French capital, from 11-14 November.

─── by Josh Bright, November 3, 2021

Featuring 177 exhibitors from 25 different countries, along with 30 publishers and booksellers, the fair represents the best of the medium, encompassing the full breadth of the photographic spectrum including the full range of styles and genres, and its earliest forms through to its most cutting–edge iterations.

In addition to the numerous returnees, the fair will welcome 29 new main sector galleries, such as AFRONOVA (Johannesburg) who will exhibit recent works by young South African female photographers, and LOFT ART (Morocco) who will present multimedia artworks by Côte d’Ivoire-born Joana Choumali.

Some of the highlights of the 17 solo shows and 10 duo shows, include, a selection of works by preeminent German photographer, Herbert List, presented by KARSTEN GREVE (Paris); BRAVERMAN (Tel Aviv) celebrates Ilit Azoulay’s work on photography and hysteria; São Paulo gallery LUME, Claudio Edinger’s series on Brazilian identity, and MAGNIN-A (Paris) introduce “Allegoria”, the latest, politically charged series, by Senegalese artist, Omar Victor Diop.

The diverse array of group shows incorporate a host of new and rare works, from unpublished dye transfer prints by American photographer, Tod Papageorge, exhibited for the first time by THOMAS ZANDER (Cologne), to rare prints by Magnum’s, Bruce Davidson, courtesy of HOWARD GREENBERG (New York). A selection of images by newly represented artist, Carrie Mae Weems, will be presented by FRAENKEL (San Francisco).

Group presentations celebrating women in photography include the work of, among others, modernists, Berenice Abbott, Ilse Bing, Germaine Krull, and Helen Levitt, exhibited by BRUCE SILVERSTEIN (New York), and new imagery by Zanele Muholi, presented by STEVENSON (Cape Town), whilst GREGORY LEROY (Paris) and CHARLES ISAACS (New York) extol the work of Mexican photographer, Yolanda Andrade, who documented the 1980s LGBT movement in her homeland.

First launched in 2018, the Curiosa sector will return for 2021. Dedicated to platforming and celebrating emerging artists, it will highlight new trends in contemporary photographic practice, including cutting-edge documentary approaches and themes focusing on identity and the natural environment.

Curated by Shoair Mavlian, Director of Photoworks and Tate Modern’s former Assistant Curator of photography, it features solo presentations by twenty artists from eleven different countries, a number of whom will be exhibiting in France for the first time. The kaleidoscopic photographs of rising London photographer, Maisie Cousins will be on display (TJ BOULTING London) as will Jošt Dolinšek’s poetic depictions of the natural world (PHOTON Ljubljana).

Additionally, for the first time ever, Paris Photo Online Viewing Room will open to the public from November 11-17th.

Powered by Artlogic (the industry leader in digital solutions for the art world) it provides a platform for galleries and book dealers, allowing them to expand on their physical offerings, and, an opportunity for those collectors and photography enthusiasts who are unable to attend in person, to peruse and purchase artworks, discover new talent, and connect with galleries and art book dealers from around the world.

The 24th edition of Paris Photo will run from 11-14 NOV 2021. For more information and to purchase tickets, visit their website.

All images © their respective ownersSHARE:839

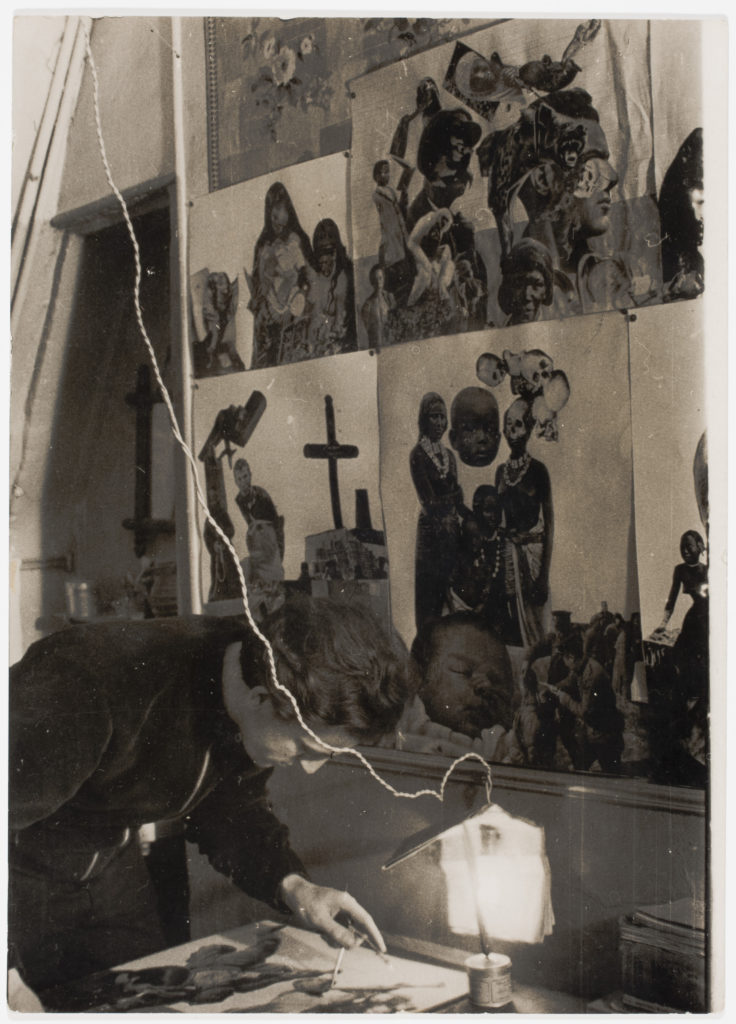

]]>Are there too many images in the world? Too many of the wrong kind? Too many that we don’t like, or want, or need? These feel like very contemporary questions but they have a rich and fascinating history. A Trillion Sunsets: A Century of Image Overload takes a long look at our worries and compulsive fascination with the proliferation of photographic images. The exhibition highlights unlikely parallels and connections across the decades. From picture scrapbooks to internet memes, from collage and image appropriation, to art made by algorithms, the exhibition offers powerful insights and new perspectives on our long love/hate relationship with images.

Artists include Hannah Höch, Nakeya Brown, Sheida Soleimani, Walker Evans, Sara Greenberger-Rafferty, Guanyu Xu, Hank Willis Thomas, Robert Capa, Barbara Morgan, Richard Prince, Louise Lawler, Andy Warhol, Pacifico Silano and John Baldessari.

International Center of Photography

79 Essex Street, New York, NY 10002Jan 28, 2022 – May 02, 2022

https://www.icp.org/exhibitions/a-trillion-sunsets

Your background is a degree in Art History at the University of Arizona in Tucson. Was curating art always a goal?

I first wanted to be a photographer. I was lucky enough to grow up in Tucson, where one of the best high school programs for photography is located at Tucson High School, and I trained there and thought I would become a photojournalist. When I was 18 I looked for work at the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona, a place I had visited since I was 14, and I was hired to catalog the Edward Weston Project Print Collection. This was an amazing leap on their part, to hire a teenager to do something like that, and it changed my life. I decided to become a curator while working there during the next five years. I’m not sure what lead directly to that decision; I was there because I loved the medium and liked being around pictures. It consumed me. I was able to do many things and had access to their great collections of photography and archival materials, and in time it just seemed obvious that my career would be in curating.

You’ve been with the Corcoran Gallery of Art for over 11 years. Were you a photography intern at another museum prior to that? When did your fascination with postwar American photography grow into a passion?

I’ve worked at three museums. From the Center for Creative Photography I went to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, where I worked for Sarah Greenough as the archivist for the Robert Frank Collection and served as the assistant for the retrospective Robert Frank: Moving Out. After Moving Out was completed I was hired at the Corcoran by one of that exhibition’s curators, Philip Brookman. Between the National Gallery and the Corcoran I worked briefly at the Library of Congress and the Washington Project for the Arts on specific projects. I’ve had incredible luck in that I’ve always worked for great people and had fascinating jobs with great collections. “Learning from the experience” has become the meaning of my life.

The amazing access I had to the work of Robert Frank is what drove me to specialize in post-war American photography. It’s unfashionable to use the word “genius” these days (and he probably doesn’t like hearing this) but Robert really is one. For 4 ½ years I was able to work every day with his work prints, proof sheets and negatives, and to think exclusively about his photography and his books. I began to think of American photo history as it led to him and grew out of his influence. Ultimately my understanding of art, politics and life was affected by his visual legacy.

In addition to your work as a curator, you also teach the history of film and you have organized a number of film series for the National Gallery including “The Films of Gordon Parks,” a photographer who donated 227 of his works to the Corcoran, following an exhibition of his work. Now that we have entered the digital age and high quality DVDs are readily available, do you see more still photographers creating narrative film-like presentations and more collectors turning to film and video as collectible?

A couple years ago I saw a multimedia narrative presentation of still and moving images by an artist while judging work for a grant-making organization. It was an amazing packaging of disparate documentary works on a single subject. Unfortunately I have seen nothing like it since. Some individuals are collecting media arts in digital form, though very few have offered such works as gifts to the Corcoran. I’m not sure whether the number has increased dramatically in recent years, though certainly more artists are making work for presentation on DVD, whether in installations or as projected pieces. The collectors I know of who acquire lots of projected media works are the bravest ones, the ones collecting on the cutting edge, the ones least concerned with displaying the object quality of their acquisitions.

The Corcoran Gallery of Art is rooted in Washington DC’s history. As a privately funded museum in 1869, it was founded “for the purpose of encouraging American Genius.” William Wilson Corcoran, the philanthropist whose collection of American Art was the basis of the museum, is reputed to have bought work only from artists with well-established reputations. Today the Corcoran stands in the shadow of much larger government-funded Washington museums. Competition is fierce and photographs from well-established artists have reached the same stratospheric heights as painting and sculpture. Does the Corcoran still adhere to its founder’s dictum of collecting only blue-chip art?

“Blue-chip art” can be interpreted a number of ways: while it seems to generically refer to work of a high quality, it also implies a high prospective investment value, or work by “name” artists, in the sense of “blue chip stocks.” And in that sense we do not acquire only blue chip work, because to do so would violate the very nature of photography, which in my view is a democratic medium. We acquire documentary and vernacular work as well as fine art photography, and we acquire work by younger and lesser-known artists as well as established figures. Both in photography and in contemporary art, collecting means taking risks, and much of the best work in our collection has come because we have tried to remain open-minded and take chances. Having said that, we are currently re-focusing our energies to plug certain gaps in our holdings, and that will mean targeting specific artists and particular works.

We do have many great collections of photography in Washington, some of them vast and encyclopedic in scope, such as those at the Library of Congress, the National Archives and the various museums of the Smithsonian. Because they are here, we do not need to duplicate what they do. And we couldn’t, even if we wanted to. So we try to build our collection and make it better than before.

Considering that photography was in its infancy when William Wilson Corcoran bequeathed his collection to the museum, how did the photographic collection begin at the Corcoran? Was there a major donor who began it with a similar passionate interest in American Photography? According to David Levy, director of Corcoran Gallery for many years prior to resigning in 2005, photography collecting was pioneered by the Museum of Modern Art, the George Eastman House and the Corcoran. Who were those pioneers at the Corcoran?

While the Corcoran is an important part of the story of the institutional recognition of photography as art, we are not pioneers in the sense that MoMA or the Eastman House are. But we did begin accepting photography into the collection in the 19th century, and we began exhibiting photography during the Pictorialist era. William Wilson Corcoran himself is likely the person who brought the first photographs into the collection. But the real “pioneers” of photography at the Corcoran were the people who made the medium an active part of the museum’s program in the late 1960s and into the 1970s and 1980s: Walter Hopps, Jane Livingston and Frances Fralin. They all did groundbreaking work during their respective tenures at the museum.

The Corcoran also is well known for its School of Art and Design (now College of Art + Design) founded in 1890. Is it a common practice for alumni to contribute to the Corcoran’s photography collection?

The collection does include the work of Corcoran alumni and faculty members. From the 1970s on, the museum has been an important force in the local practice of photography, and it was a natural step to reflect that in our collection. We still do so, though we are particularly cognizant of the potential for conflicts of interest. But to give a recent example, last year we acquired works by Joyce Tenneson that were made during the early 1980s when she worked in Washington.

The Corcoran appears to be undergoing a major shift in direction since 2006 when Paul Greenhalgh was appointed as director and president of the Corcoran. The long touted new addition by architect Frank Gehry has been sidelined, exhibition schedules have been dramatically altered, and there is talk of a return to generating exhibitions from the Corcoran curatorial staff rather than relying on exhibitions organized by other institutions. However, the current exhibitions Ansel Adams and Annie Leibovitz: A Photographer’s Life, 1990–2005, both through January 2008, were both organized by other museums. What plans does your department have for fulfilling this new directive?

The Corcoran has and will continue to host interesting traveling exhibitions, just as we organize our own exhibitions and send them out on the road. Both Ansel Adams and Annie Leibovitz: A Photographer’s Life, 1990–2005 are examples of shows organized elsewhere that we thought our audiences would want to see. But we’ve been making our own major exhibitions all along and will continue to do so. Under Paul Greenhalgh’s leadership we are changing the way we make major exhibitions, but I don’t think we are planning to ignore other museum’s exhibitions. We are still always looking to see what is out there that fits well with our program, and we are well aware that we can’t organize every type of show our audience wants to see.

We are planning several major exhibitions that involve photography. Right now I am organizing Richard Avedon: Portraits of Power, a survey of Avedon’s portraiture that deals with politics and power. The work included spans his career and the show will be timed to the American presidential election season, opening just after the conventions in Fall 2008 and running through the end of the inaugural in January 2009. Philip Brookman, who is now our Director of Curatorial Affairs, is organizing an Eadweard Muybridge retrospective for 2010. And a team of our curators is working on a sweeping survey of Postmodernism for 2011, which will include many photography and new media works.

Where will you turn to for these new curatorial initiatives? What feeds your curatorial imagination?

I’m really interested in the intersection between photography and politics, and in the ways that photographers use the medium to reflect the social world. I’m not sure if I developed this interest from being in Washington, or if I came here because this was the perfect place to view the medium through this filter. Working on the Robert Frank archive at the National Gallery, in a building near the U.S. Capitol, was certainly an influence. Seeing how artists think when installing their work in the Corcoran, which is a few hundred feet from the White House, has been an ongoing revelation. Context is so important: we always think about how images reflect the country — and its people, its promise and problems — when considering our exhibitions.

You are a photographer as well as a curator. Your work was included in the Crosscurrents series at the University of Maryland in the 2004 “Room Full of Mirrors.” The 14 artists in the exhibit were described as ‘using the collage aesthetic; incorporating various methods using chance and accident to allow creativity to work through them not from them.’ You have also been involved in a grass roots organization of Washington area artists WPA\C that until recently was part of the Corcoran Museum. You have juried exhibits for many organizations. Clearly, you have a pulse on the kind of work being generated by contemporary and as yet unheralded photographers. What trends do you see there?

Well, interestingly, I don’t feel all that “in touch” right now! I’ve been buried under the work I’m doing on the big shows we have scheduled. But when I do have time to look at new work, I’m really interested in how photographers are evolving their representation of capitalism and its discontents. Gursky’s rational re-orderings of the middle class world of consumption and power are giving way to more explicitly political visions like Chris Jordan. I’m also seeing more work I like that seems suffused with a blanket of anxiety, like that of Amy Stein, Noelle Ta, and Kate MacDonnell, all of whom have roots here in D.C. And I am interested in the ongoing return to earlier photographic processes in the face of the medium’s eclipse at the dawn of digital.

You were also part of a panel discussion, “The Artist’s Responsibility in a Political Environment” that reflected on the role of the artist as a political pundit and activist. Documentary photography has a long established place in political activism but what about the new photography where lines are blurred between the real and the created?

Well, that’s an interesting question. I have to say that I think most fictional, performative and theatrical work is really boring. It is, I think, the most overrated avenue of photography I can think of. Most of the work I see shows just how hard it is to make a single image out of set design and stage direction — usually the work people praise is incredibly awkward, emotionally empty and totally unrevealing. I am kind of fascinated by own negative response, though, and I want to investigate this work more so I can see why I reject so much of the work I see. I recently got Lori Pauli’s exhibition catalog from her show at the National Gallery of Canada, Acting The Part (Merrell, 2006) so I can learn more about it. Maybe it will temper my attitude.

The Corcoran’s Director Paul Greenhalgh was quoted in a Washington Times interview as saying: “This institution should be a think tank. We’re not in the business of pleasing people; we should also challenge and educate.” With that in mind: what would be your ideal exhibition?

My ideal exhibition is a survey of the medium through the notion of the uncanny, first defined by Freud as the state where something is both familiar and foreign at the same time, resulting in profound discomfort and anxiety. This show would look at photography’s history as a vehicle for exploring what lies beneath the visible: the uncomfortable truth below the pleasing, understood and well-ordered surface. My favorite photographs are the ones that destabilize our consciousness rather than confirm what we think we know.

Any plans for that in the future?

Well, fortunately yes! That show is tentatively scheduled at the Corcoran for 2011–12. If all goes well it will be the next big show I work on after Richard Avedon: Portraits of Power.

The Corcoran Gallery of Art is located at New York Avenue and 17th Street, NW, Washington, DC. Please see the Gallery’s website for hours and admission fees.

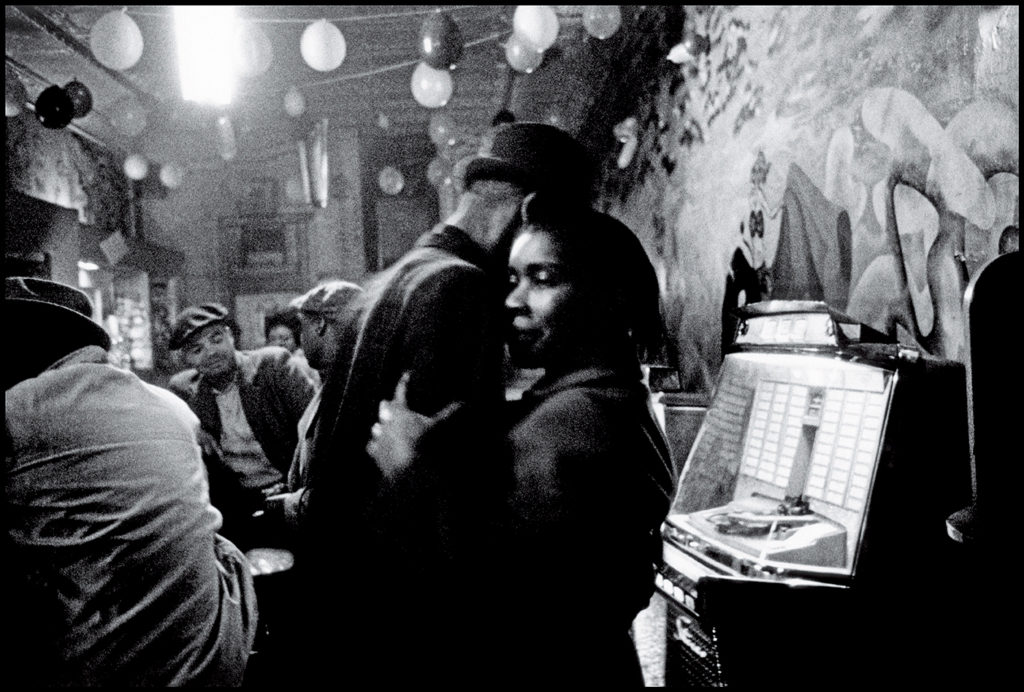

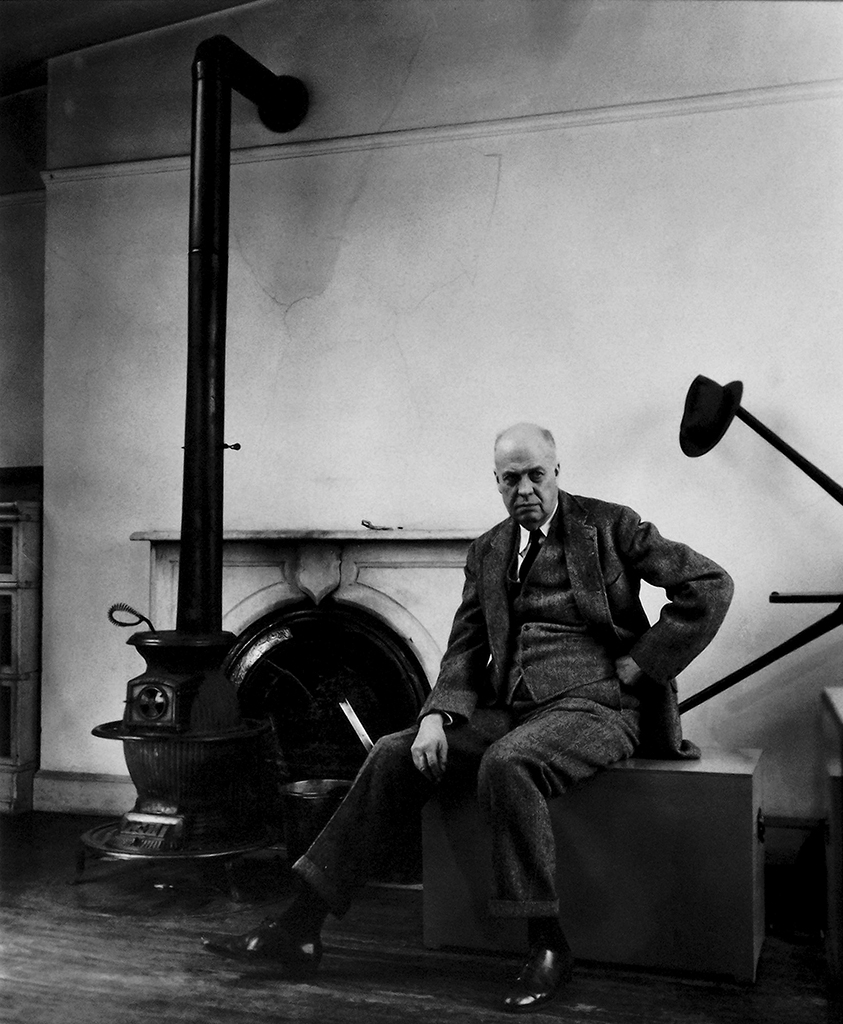

]]>An intense and well–spoken man, Bruce Davidson has proved to be one of the most prolific photographers of the 20th and early 21st centuries. The list of his photographic series that have culminated in books is startling. He has published 16 book titles. A partial list includes East 100th St. (1970 and 2003); Subway (1986 and 2003); Central Park (1995); Brooklyn Gang (photographed in 1959 and published in 1998); Portraits (1999); Time of Change, Civil Rights Photographs 1961–1965 (2002); England/Scotland 1960 (2005); and Circus (2007). In particular, the modern classic East 100th St. has afforded Davidson a special niche in photographic history. With a background in what many would characterize as photojournalism (he is a member of Magnum Photos), he introduced innovation by utilizing a 4 x 5” view camera to create portraits with depth and complexity — and yes, beauty — of the residents of what was termed in the late 1950s “the worst block in Spanish Harlem.” The impact of East 100th St. was heightened by the charged emotional atmosphere of a nation struggling with Civil Rights issues.

Bruce Davidson is known as an artist whose work ethic is unusually consistent. He invests a great deal of thought in his projects before he begins, but that is only half the equation. The other half is sheer, non–stop work over extended periods of time to accomplish his goals. His approach requires an extreme level of organization, right down to the careful filing of prints. He brings that same work ethic and organizational ability to the presentation of his exhibitions in the art world. Although a veteran of the museum world — his first one–person show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York took place over 40 years ago, in 1963 — he has come to the art gallery scene relatively recently, in the 1980s. In a short period of time he has emerged as an important figure in the collectibles market, partly because his body of work is large enough to sustain exhibition after exhibition in rapid succession. It is notable that in addition to investing time in preparing exhibitions and arranging his archive of past work, he still moves forward with the act of photographing the present and planning future projects with joyful intensity.

At the time of this interview, The Jewish Museum in New York City is presenting Isaac Bashevis Singer and the Lower East Side: Photographs by Bruce Davidson. Spanning the years 1957 to 1990, the exhibition features 40 intimate photographs of Singer, the revered Yiddish author, as well as residents of the Lower East Side Jewish community, including visitors to the Garden Cafeteria in that location. Could you tell us a little about your relationship to both Isaac Bashevis Singer and the world of the Lower East Side?

Isaac Bashevis Singer lived in our building here in New York on the fifth floor. I had photographed him years before on a magazine assignment. We just became neighbors. Also, I was interested in trying to find out about his world because that was the world of my grandfather. I wanted to find continuity. My grandfather came to the United States from Poland as a boy of 14. He learned English, became a tailor, and had a very good business. He went from being a tailor into manufacturing with his older son Leonard and Leonard’s wife Ruth, and that company is very large now.

I was born in 1933 and grew up in Oak Park, Illinois. My mother was a single parent. She was working in a torpedo factory during World War II. My brother and I could really fend for ourselves. We were very self–sufficient. We learned to cook. We learned to clean. We learned to meet our mother on time at the bus stop and carry home very heavy packages of groceries. My younger brother became an eminent scientist. I became a photographer. That was all part of being with my grandfather. For a while we lived with my grandfather in the home my mother was raised in. I began to sense there was something strange about my grandfather, there was some secret. There was something he left behind and he never really talked to us about it.

I was the first son in our family at that time to be Bar Mitzvahed. Our synagogue was a small clubhouse synagogue. I mean it was not a synagogue at all; it was a clubhouse with a small congregation. While I was reciting the Hav Torah during my Bar Mitzvah, I could see a box that I knew would be a camera on the rabbi’s desk. During the 1940s, cameras were scarce. Film was scarce. I had been taking pictures since the age of 10, and was very excited about receiving my first good camera and two rolls of film.

I was taking pictures and my grandmother emptied out a closet in the basement where she stored bottles of jelly. I began developing and making small contact prints in it. I even wrote on the outside of the jelly closet — I mean, it was small; I could barely fit in it — but I wrote “Bruce’s Photo Shop.”

You know, there is a similarity between photographing and tailoring. You learn to make the pockets straight, and actually you have the persona of the person you are fixing the jacket for. The persona is definitely there. It’s craft. And photography has craft also. So my grandfather sewed buttons and I sewed photographs.

So I would say that entering the world of Singer and the Lower East Side was really entering the world of my grandfather, but I am in no way an observant Jew.

As a Midwesterner transplanted to New York, you have demonstrated your great love of the city and its inhabitants in many series of photographs. Could you expand on your feelings about New York and how the city inspires you?

The town of Oak Park was a very small community. It was the home of Frank Lloyd Wright and Ernest Hemmingway. I have said that I am not a practicing Jew, but I am in the sense that wherever I photograph in New York — or wherever I photograph anywhere — it becomes to me a spiritual space in that I think there is a solemn responsibility when you have a camera. Although I don’t read the Torah, I do read the Torah of life, and my own personal Torah, so it wasn’t a big deal to leave Illinois to come East, to go to school, and to explore New York. My very first day in New York — my mother had remarried and we were staying at the Plaza Hotel — I began to explore. I went outside the hotel and I was photographing the pigeons and people with my Rolleiflex. My mother or my stepfather came out and said, “You’re using up all your film.”

I think New York is probably the most important and the most alive city in the world. It’s the most diverse. It’s the most difficult. It’s the most challenging. I have found that over the years I have been able to enter worlds within worlds in the city, beginning with the Circus series, then the Brooklyn Gang, and later the Subway and Central Park, and other entities. I entered worlds within worlds and they became sacred places for me. I no longer entered a shul; I entered the sacred space of people’s lives.

You attended the Rochester Institute of Technology (1951–54) in Rochester, New York and Yale University (1955) in New Haven, Connecticut. In other interviews, you have spoken of taking classes at Yale with the artist Josef Albers. Can you tell us about that?

Yes, I took Josef Albers’ color course. I also took his drawing course, although I didn’t draw. I was there as a photo student. But his color course really left an impression, and I began to understand the meaning of color. That isn’t to say I was going to use color to become a color photographer. I understand color. I know how to use color, but I do not prefer it. I prefer black–and–white. My films are in color, but the Subway body of work is the only major body of still photographs that I have in color, except for a number of landscapes made on Martha’s Vineyard over the years.

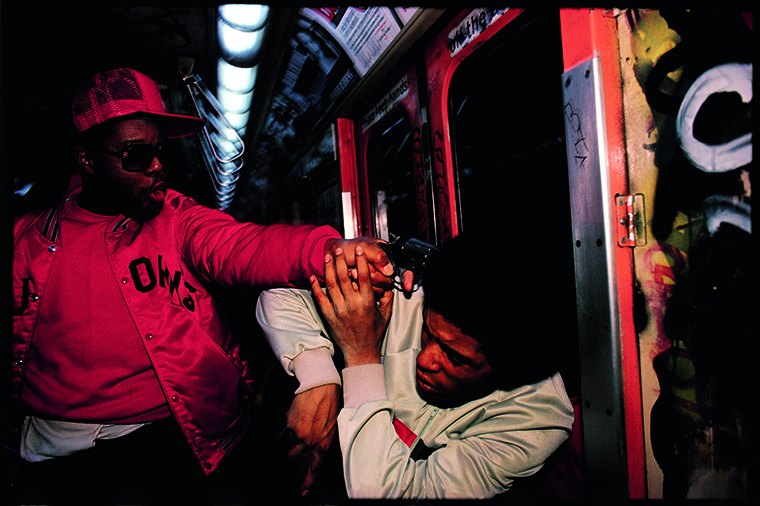

I started photographing the subway in 1979 or 1980 in black–and–white, but I saw another dimension of meaning in color. The graffiti, even the iridescent, fluorescent lighting in the subway, all had a kind of meaning — there was sort of a poisonous green–blue light down there that had color meaning, so I switched. I remember going out at day with one camera with color film and one camera with black–and–white, and I redid each picture. I would take pictures in black–and–white and then I’d switch to color. There’s a difference, you know, not only because one is black–and–white and one is color. There’s a difference in the “moment to moment” and you have to choose.

You have compared the subway to the Theater of the Absurd. Do you still think of it this way?

Yes, but it is also the most democratic space in the world. Anybody, rich or poor, healthy or unhealthy, rides the subway. The graffiti at the time was written all over the place and was what is called the hieroglyphics of anxiety, of anger, of frustration, of “I am invisible but my marking remains.” You know, dogs pee on a pole but graffiti artists draw their name. The dog says, “This is me. I am here.” They’re making their marking and then somebody else comes over and pees on that marking and makes a new marking; so that was the dynamic. But the subway could be excruciatingly beautiful. It could be the sexiest environment I’ve ever been in; we can’t go into details but the subway can really be sexy.

How did all this relate to the mood of the city at that time?

At that time, about 1980, the trains were running poorly. They were very unsafe, there were a lot of muggers, there was graffiti written all over the place. I think the city was in default at that time, also. It was a chaotic, neurotic, pathetic time. And I chose…the subway really chose me. I started to go into it with a camera out, with a flash. A safari hunter. In fact I fashioned myself after the tiger hunter Jim Corbett. His books were written for boys but I liked them. So I became the tiger hunter. When you hunt tigers you have to watch your back. Anyway, I had all sorts of fantasies going because that’s what the subway can be. It could become as sacred as a church pew, it could be beautiful, it could be upsetting, it could be depressing. Anything goes, and I fed on that.

You have stated that your work in the subway was an antidote to depression. How was that so?

Because the subway was more depressed than I was. And in photographing in color — I wanted the color to be vibrant — I drew a parallel between fish in the deep sea where you see no light and yet you have iridescent colors when light is shown on them. I wanted to transform the subway in some way so that from a beast I made it beautiful and when it was beautiful I made it bestial, so that anything could come to me or reflect off me and rebound in the subway. I left my imagination and awareness open to the moment. The color experience was also a human experience.

Did you find it an experience of loneliness?

Yes, I seem to be attracted to things in transition, things that are isolated, maybe alone. I gravitate to that which has a certain tension because it’s in transition. The circus was in transition from tent shows to coliseum shows, from small, intimate family circuses to large extravaganzas.

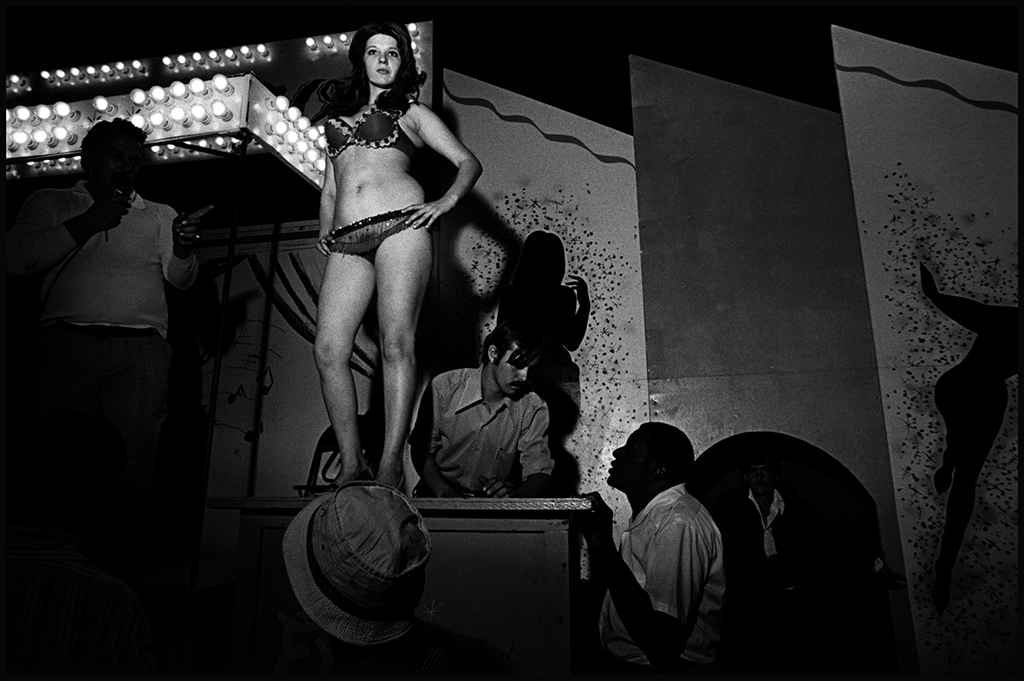

Let’s talk about your circus photographs. Historically, many artists of the 20th century, such as Pablo Picasso, Alexander Calder and Edward Hopper, have been drawn to clowns and the circus. What do you think is the source of the appeal and how did you yourself get started with the circus?

Magnum in New York had an incredible picture librarian by the name of Sam Holmes. Sam was an amateur trapeze artist. He was the one who told me about the circus in Palisades Amusement Park in New Jersey, which was the beginning of my circus work in 1958. I was not drawn to the circus per se, but to the clown who was a dwarf. It was the combination of attraction and repulsion that I felt standing next to him outside the circus tent that drew my attention and sustained a friendship with him.

His name was Jimmy Armstrong. He was melancholy. He was sensitive, very sensitive to everything. He wasn’t depressed but he was poetic. It’s almost like he was a performance artist. Even when he was outside the tent, he was performing; he was directing the camera to what he could feel at the time. I never said, ”Jimmy, why don’t you pick up your trumpet and blow it.” I waited for him to do it. He worked hard in the circus. He was carrying two heavy buckets of water. And you know, people in the circus liked him. I have a picture in the Circus book of a roustabout giving him a massage. He didn’t have to do that. But that was the nature of the circus, too — they were a family. They were kind of like Magnum, but with elephants.

Jimmy and I had a very silent friendship. I just observed him. He allowed me to observe. He also allowed me to see things that might have been embarrassing for him, or even dangerous, like walking through a crowd of children. You know children can be quite cruel to dwarves. Where else can you find someone with the same size head as your father, but half your size? At the end of our two–month trip together I bought him a Yashica Rolleiflex–type camera that he could hold in his hand. He often said that I was his best friend, even though I wasn’t really close to him, except in the sense that I was with him all the time. What made it so compelling was that we all have a dwarf in us, and that dwarf can come out in various ways: something small and compressed as being repulsive.

The picture I took of him peeking out of the van [on the cover of Focus Magazine] is an early ”confrontational” photograph. It isn’t that other photographers hadn’t done confrontational photographs, but it was something that wasn’t usually done. In photojournalism at that time you were supposed to be the “unobserved observer.” So no one looked at the camera because the camera wasn’t “there.” Here I made the camera “there.” I think that was a very penetrating thing. The fact that Jimmy Armstrong, the clown, allowed me that close into his soul was important to me.

He was married and had children. He married a normal–sized, but short, woman named Margie. Jimmy is dead now, and Sam and I can’t seem to find Margie. Sam found out that Jimmy, during World War II, could crawl into the fuselage of the bombers to do wiring. So he joined the war effort as a dwarf. He had a lot of lives. He was a musician. He was photographed by many different photographers, including André Kertész. He was even in a movie, Cecil B. DeMille’s The Greatest Show on Earth (1952) with Charlton Heston and Betty Hutton.

After I left the circus, he sent me a route card every once in a while. This was his schedule, so I knew where he would be. I would call the chief of police of a town and say, “My cousin is a dwarf in the circus. Could you get a message to him?” The chief would assume that I was a dwarf too, and he would jump into his car and run out with the message, “call me,” or whatever. Over time I lost track.

Going back to the period of your life following Yale, you were in the military from 1955 to 1957. Was there anything about that experience that relates to your photographic work?

Absolutely. In the army, I was in the Arizona desert for about a year. I used to hitchhike to Nogales, which was only 40 or 50 miles away, to photograph the bullfights. Patricia McCormick was a female bullfighter and I became somewhat friendly with her. In hitchhiking to Nogales I came upon a small town called Patagonia. It was really a railroad siding and a bar and a gas station and a post office and that was about it. There I met an old guy who was driving a Model T Ford and we became friendly. He was a miner. Every weekend I stayed at his bunkhouse and photographed. As I look at that body of work now, it seems very whole to me and I find it amazing.

It was the precursor to the Widow of Montmartre, which I made the following year, when I was transferred from Fort Huachuca, Arizona to Paris, France. There I met a French soldier who invited me to have lunch with him and his mother in Montmartre. After lunch I was standing on the balcony with my Leica and I saw an elderly woman hobbling up the street. I took a picture. The soldier said, “Oh, that woman lives above us and in fact she knew Toulouse–Lautrec, Renoir and Gauguin.” She was in her 90s in 1956, you see. She was the widow of the Impressionist painter Leon Fauchet. So the soldier introduced us and that series became the Widow of Montmartre. I lost track of that soldier for many years, but recently found him. He still lives in the same area. He’s one of the painters at the top of the hill in Montmartre.

At that point in my life I decided to show my work to Magnum Photos in Paris and to Henri Cartier–Bresson. Well, actually I had no idea of Cartier–Bresson. He was beyond reach. I left my photos at the Magnum office. They called me and said, “We would like to show your work to Cartier–Bresson.” Then I had an appointment with him, and that was the beginning of my career, and my life in photography.

Henri Cartier–Bresson is known as one of the most influential photographers of the 20th century. Could you talk about the effect of Cartier–Bresson on you and your work?

Cartier–Bresson took me under his wing. He tried to get me to read more, to reflect more, to be more disciplined. Over that year we had a professional relationship in which I occasionally showed him my work. Of course he had seen the Widow of Montmartre contact sheets. In fact, I just donated those vintage contact sheets from 1956 and about 17 prints to the Fondation Cartier–Bresson in Paris.

Cartier–Bresson is known for developing the concept of the Decisive Moment, one definition of which is the moment of stillness at the peak of action. Do you see yourself as being influenced by the idea of the Decisive Moment?

Well, the concept of the Decisive Moment has never been absolutely clear to me. To me it’s the Decisive Mood, and not the moment. I think that, sure, there is a decisive moment in life in everything we do. There’s a certain timing. But it isn’t just about timing, a man jumping over a puddle. The Decisive Moment is an internal thing. If you become decisive and you enter life in a decisive way, the moments will appear, as long as you are in tune. So what we are really talking about is a way of looking at life, a kind of balance. Sure, there’s geometry, there are moments and all that, but my photographs are more of a mood and they are cumulative, too. They aren’t just one picture.

We’ve spoken of Cartier–Bresson. You’ve also mention in other interviews being influenced by W. Eugene Smith and Robert Frank. In an interview with the Oregonian Newspaper you said, “Cartier–Bresson was Bach, Smith was Beethoven, and Frank was Claude Debussy. They’re all in my DNA.” Could we discuss this?

Well, definitely Smith was an influence because his photographic essays published in Life Magazine were very powerful. I don’t see how anyone could do a better job on Spanish Village than he did. All his works were very theatrical. They’re almost like stage sets. I don’t think he’s given enough credit for what he’s done. To some extent I was influenced by Robert Frank, but I moved away from him completely when I did East 100th St. and, in fact, I moved away from almost everybody who might have inspired me when I did East 100th St..

You did your series on the Brooklyn Gang in 1959. It was published in Esquire Magazine that year, but it did not appear in book form — Brooklyn Gang, published by Twin Palms — until 1998. One critic has described the essay on the Brooklyn Gang as having an air of innocence about it. Do you agree with that?

Those kids, at that time, you see, were actually abandoned by everybody, the church, the community, their families. Most of them were really poor. They weren’t living on the street, but they were living in dysfunctional homes. It’s the same thing. Anyway, they were kids and the reason that body of work has survived is that it’s about emotion. That kind of mood and tension and sexual vitality, that’s what those pictures were really about. They weren’t about war. I mean, you can’t compare those kids to the kids today who have machine guns. So there is an innocence in the photographs because it reflected the kids’ innocence, but that innocence could erupt into violence.

It’s interesting that the leader of the Brooklyn Gang, Bengie, who is now 65 years old, called when I was given a large show of the Brooklyn Gang at the International Center for Photography (ICP) in New York in 1998–99. My wife and I went down together and had coffee with him in midtown, and he turned out to have had an extraordinary life. He is now a substance abuse counselor. We just returned last Sunday from his birthday party, where we saw some of the old gang members.

What caused him to contact you?

There was a reunion of the old gang members. They were looking at my photographs in Esquire Magazine and they started talking. Bengie said he had been trying to get up the courage for years to call me, and finally he just did.

Perhaps we could discuss East 100th St. for a while. You photographed on that block from 1966 to 1968. The book East 100th St. was published by Harvard University Press in 1970, and was reissued in an expanded edition by St. Ann’s Press in 2003. You received the first–ever photography grant from the National Endowment of the Arts in 1966, which you used in support of the East 100th St. project. East 100th St. appeared as a solo exhibition — your second at this venue — at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1970. How did you come to be introduced to the people on East 100th St.?

Sam Holmes, the picture librarian at Magnum who told me about the circus in Palisades Amusement Park, also told me about the “worst block in Spanish Harlem.” His cousin was a minister living on the block and working with the Metro North Citizens’ Committee. So I looked up the minister and had an appointment with the Citizens’ Committee and then I photographed for two years.

Were you attempting to create collaboration between the photographer and the subject?

Yes, one of the reasons I chose to use what would be regarded as an old–fashioned view camera on a tripod, with a flash, was that I felt it dignified the act of photography. I was eye–to–eye, face–to–face with the subject. The only thing that connected me to a camera was the little cable release, but I was really looking into the eyes of my subject. The environment was also important; what surrounded them was part of the picture, too. It was part of their expression. If the wall had a picture on it or a birdcage or nothing, it said something about them.

In some of the photographs the people presented themselves in a middle class way, very dressed up. Why do you think they chose to do that?

Well, you know, people are middle class in their minds. They may not own an automobile, but they dress very elegantly on Sunday, going to church. I had an experience in which I saw some children half–naked. They just had some little panties on and they were playing on the fire escape. I went to take that picture. The mother saw me and brought the kids in through the window. I counted the floors and went up and knocked on the door. The woman said, “You can photograph my children that way, but you must also photograph them dressed up.” So I photographed them playing on the fire escape and on Sunday I photographed the family dressed up.

Much has been made of the dark tonality of the photographs in East 100th St.. Did that tonality emerge immediately as your intention, or did it evolve over time?

When I entered a person’s home I was entering a sacred space, is the way I looked at it. It was up to the person to decide where the photograph might be made. Was it in the kitchen, in the bedroom, or in the vacant lot downstairs? Most of the time it was in the bedroom because it was a quiet space and it had artifacts or clues to their spirituality, like a cross, a picture of Jesus, a framed photograph of John F. Kennedy. Very often these dwellings were dark. I remember a photograph I took of an elderly woman sitting on a bed with towels and rags stuck into the cracks in the window to keep out the cold air. That was an important part of the photograph, which showed her sitting alone in this dark room with only one little light bulb on the ceiling. I tried to be true to the mood, to the darkness, and through the darkness I made a light because I made an image of that person’s predicament in life. So when I printed the photographs for the book I printed them in a very strong and heavy way. In fact, I was inspired by the bronze Degas sculpture of dancers at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The bronze looked like shrapnel to me. It was dark, metallic, rich, and I followed that through as a theme in the printing of my photographs. I was highly impassioned in those days with that tonality. Years later, when I was printing for the second edition of East 100th St. I opened up the tonality because I was able to: the technology had improved. I had the aid of a scanner. I made the printing a little lighter.

East 100th St. wasn’t just a documentation. It was a vision, a vision in which I reached into the tonality with a large format camera. I wanted that depth of field. I wanted to be able to see down to the street while someone was lying on the couch. The way the camera was used, the way the lighting was used, the way I saw things were all part of the aesthetic. The aesthetic dimension to East 100th St. combined with the sociological message.

How recently have you had contact with the people on the block?

A few years ago I received a fellowship from the Open Society to go back to photograph. When I returned I could find very few people I knew. They had moved on. You know, people move on. What happened in the 1960s was that a matrix of new schools, tutorial programs, all kinds of things, rippled all through Spanish Harlem. Metro North Association was the beginning of that self–improvement, reviving the community. The community itself was doing it. I photographed positive aspects of new schools, new housing, tutorial programs, a new park and ball field, a women’s health center, the vest pocket gardens, and the new mood and the street. I’ve donated all that work to the Union Settlement and it is on display there. Yes, Spanish Harlem has changed. It’s almost easier to get a café latte now than a café con leche. Some of the texture is lost, but it’s a lot safer than it was.

Obviously you maintain contact with people you have photographed over the years. Can you tell us more about that?

I do, but I don’t overdo it, because life goes on. In Time of Change, there is a picture of a woman in a shack holding a baby, made during the Selma march. I found that baby and I found the whole family recently and re–photographed them. Their lives had changed tremendously because of the Voting Rights Act that allowed the younger children to get a better education. One of the 11 children holds a master’s degree in library science and became head legal librarian at the State Capitol in Montgomery, Alabama. Almost all of the younger children I photographed have successful lives.

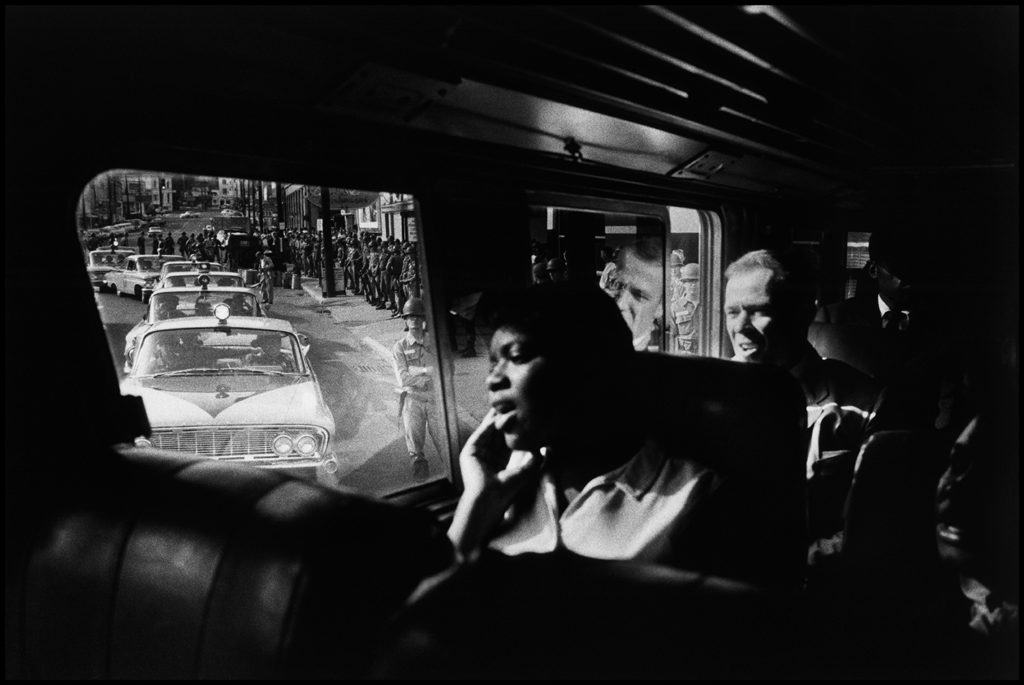

You photographed the Civil Rights Movement, primarily in the American South, from 1961 to 1965. In 1962 you received a Guggenheim Fellowship in support of this project, and in 1963 the Museum of Modern Art included these historic images, among others, in a solo exhibition. The book, Time of Change, Civil Rights Photographs 1961–1965 was published by St. Ann’s Press in 2002. In that same year, the International Center for Photography presented an exhibition of Time of Change. When you were photographing these events in the early ’60s, did you find it a frightening experience?

Oh, yes, because if you made a mistake and you got into a situation that you couldn’t get out of…that almost happened to me. I photographed a Ku Klux Klan meeting, but I drove my little Volkswagen bug too close to the cross. When they lit it, they said, “New York license plate so–and–so, you’re too close to the fire.” I knew that that was not going to be cool, to have New York license plates at a Klan meeting in Georgia. I stayed a while, took a few pictures, and then left.

Would you call the Civil Rights photographs a turning point in your life?

Well, it certainly made it possible for me to understand what I was getting into in East 100th St.. It was the prelude to East 100th St.. It was like my homework. I had borne witness to what was going on in the South and to some extent become sensitized to what was happening in the North, too. Without that background I don’t think I would have done East 100th St. the way I did.

What about your early fashion days? How did that happen?

The story I heard was that after Brooklyn Gang was published, Alex Lieberman, the creative director of Vogue Magazine, was having lunch with Cartier–Bresson. He asked Bresson if he thought the young Bruce Davidson could do fashion. Bresson’s answer was: “If he can do gangs, why can’t he do fashion? What’s the difference?” So I did a lot of fashion for about three years.

I rarely do fashion now. I came to a point in the Civil Rights Movement where I was doing fashion and also protest marches and I couldn’t equate the two things, so I gave up fashion. I’m good at fashion photography but it doesn’t give me meaning. It’s like cotton candy. It looks beautiful, but it melts in your mouth, and the sugar can rot your teeth.

During the early 1990s, you did an extensive series on Central Park here in New York, which culminated in the book Central Park, published by Aperture Press in 1995. How did that series come about?

I did a body of work for National Geographic Magazine called The Neighborhood, in which I retraced my boyhood steps in the Chicago area. After I completed that the editors asked me what else I would like to do. I said I’ll make a list of ten things. To make it an even ten, I added Central Park. We used to take the kids there and at that time it was like a dust bowl. You never knew when you were sitting with your children if there were hypodermic needles sticking them. Then the editors said, “Oh, Central Park, that’s a good idea.” I said, “I need four seasons and I need to be in black–and–white.” They said, “Oh, no, we are a color magazine. You have to do it in color and we can give you only three seasons.” So I went out and I started photographing Central Park. I exposed 500 rolls of film. Then we had a presentation. The next morning I got a call from the editor–in–chief Bill Graves, who said, “We’re pulling the plug on this project. Think of something else.” So I said to myself, “Good, I’m free at last,” and I went back to Central Park with my Canon Cameras and I spent the next three years photographing in black–and–white.

That series has been called a love poem to New York. Do you think of it that way?

Yes, the series I did was a love poem, but it was not a sweet poem. It had a fierceness to it. It had an edge to it, as I explored the layers of life.

What are you interested in photographing at present?

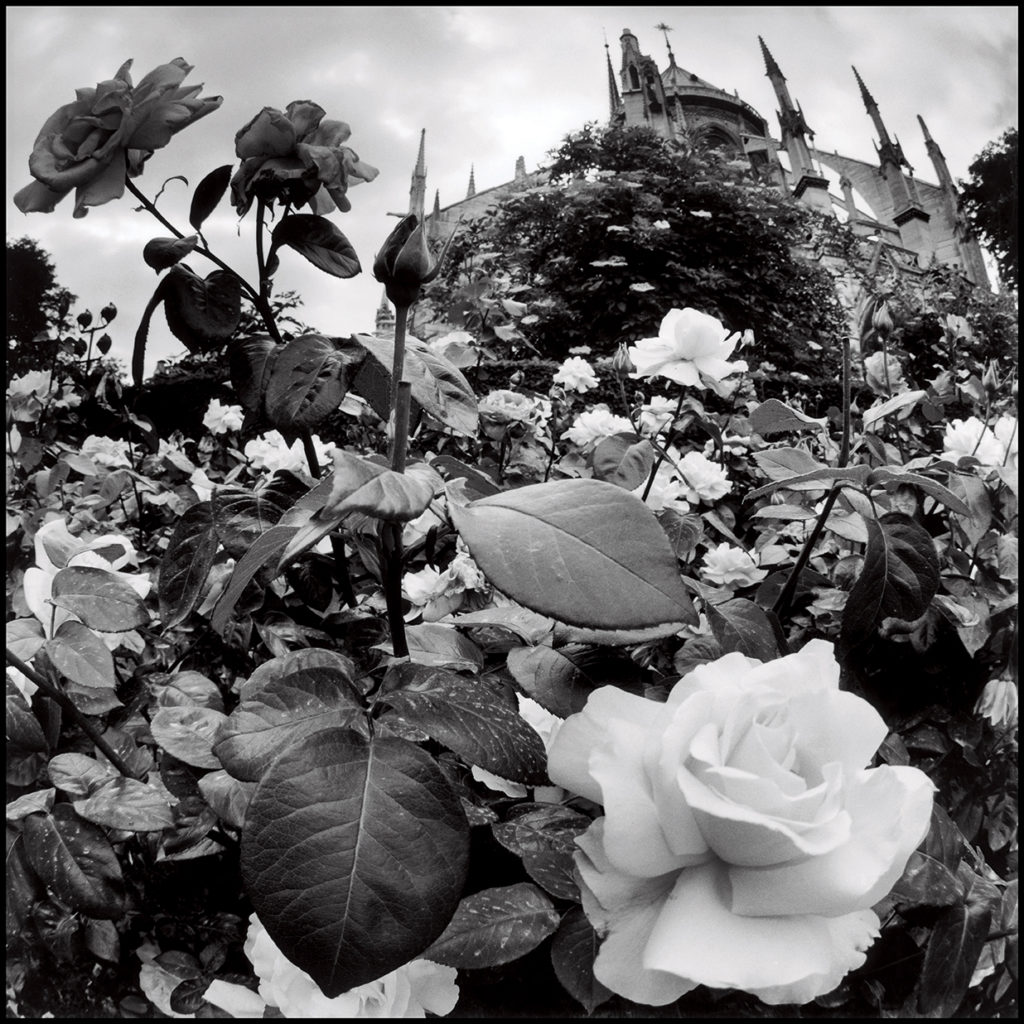

I’m interested in the balance of nature right now and the meaning of the vegetation that at times goes unnoticed in our lives. I just finished a large body of work called the Nature of Paris. It was shown at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris. The exhibition opened in June of 2007 and closed in September. In Paris I think I made an homage to vegetation. In that city the monuments take over. We go to the Eiffel Tower and we don’t realize there’s a 500–year–old tree growing right next to it. When you see the pictures it will be self–evident. I’m interested in raising people’s consciousness, my own included, to the meaning and the need for green space and vegetation.

When I began the project in Paris, I began by photographing some people in nature. For instance, my assistant found an elderly woman in the cemetery in Montmartre, a woman well into her 80s or 90s. There were cats standing on the tombstones, waiting for her to come to them with food. They wouldn’t just rush in. I photographed her and also lovers in the park and all that kind of stuff, and I was getting sick from it. I edited it all out, including the panoramas, even though the panoramas were successful, I thought. I edited all the 35mm pictures out. There was something I was doing with the square format that was coming through to me. In the end the whole show was nothing but the Hasselblad 2 ¼” photographs. I was able to disinvest all that other imagery, which I’d already done, into something that I hadn’t done, something that was new to me, fresh to me. And challenging.

I’m looking for another city that would be the extension of Central Park and Nature of Paris. I would like to continue the concept that was born through the Paris photographs.

At what point did you become interested in selling your photographic prints through galleries?

I was too busy photographing during the 1970s to become affiliated with a gallery. I became interested in the 1980s. It was Howard Greenberg who really brought me out of the fine art world “shadows” and into the sunshine. I had my first exhibition with his gallery in New York in 2002. I felt that Howard could really embrace my work and he did. Howard is, as they say in Yiddish, meshpokha, he’s family. He understands the work, he’s honest, he’s energetic, and he assigned me Nancy Lieberman, who is wonderful, and who manages my work for the gallery. Recently she arranged for my wife and me to go to Greece for a 75–print commemorative exhibition for the Hellenic–American Institute in Athens.

On the West Coast, Rose Shoshana and Laura Peterson of the Rose Gallery have mounted some of the most beautiful exhibitions I’ve ever had. They did a dye transfer color show of Subway that was amazing to see, and before that, Brooklyn Gang. They had a patron who underwrote the creation of a portfolio of Subway containing 47 very large dye transfer prints (20” x 24”) in an edition of 7. I think there are only two portfolios left.

I am now working with three people: Howard Greenberg Gallery, in New York, Rose Gallery in Santa Monica, California and the Sandra Berler Gallery in Chevy Chase, Maryland

After 9/11, did you have a desire to photograph events here in New York City?

Well, I went down a night or two to 9/11 to photograph. It was very difficult to get permission to work. I had sent a whole portfolio of photographs — not of 9/11 — to Hillary Clinton, but it never got to her. The FBI just X–rayed things and kept them, so I got those prints back a year later. So I didn’t have permission to get down there, but I knew someone who operated a building nearby and they were housing police overnight. He said the captain would be willing to take me around for a while at night, but that was all I could get.

In my slide presentation I have a photograph of the Twin Towers at night with the Statue of Liberty before 9/11. It’s a photograph that can be taken only with a 1700mm telephoto lens. There are only two in the world. I borrowed it from Canon. My wife did the scouting. She found a pier that jutted out a quarter of a mile into the bay. It’s a Kodachrome picture of the World Trade Center at night, lit by the office lights in the windows. When I took it I thought, oh, yeah, this is a perfect symbol of consumerism, materialism, all of that. But after 9/11 it became a memorial image, like two candles set on the altar of life and death.

Esquire Magazine gave me an assignment to photograph some aspect of America after 9/11. I just didn’t feel comfortable going someplace like the Grand Canyon, so I went to Katz’s Delicatessen. I spent a month at Katz’s making photographs of people eating pastrami, because I wrote, “Pastrami and Peace Go Together.” You feel very peaceful when you are digesting pastrami. I felt that freedom was about being able to photograph the impossible or the vulgar or whatever, or simply people enjoying themselves.

Did you feel the urge to photograph the people around Union Square who were looking for their relatives?

No. I felt there were so many photographers there that it would be well covered. I don’t like to photograph where there are a lot of photographers. It doesn’t feel right to me. I like to go where no one else has gone. Also, you have to understand my feelings. The whole thing knocked the wind out of my sails.

What projects are you involved with at present?

I still do some editorial photography. In fact, I just did a really interesting project with CareOregon, a private healthcare company that asked me to photograph a number of their members. These are people who are very, very sick. They are in their homes, not in the hospital. CareOregon made two beautiful exhibitions of the work, one at their headquarters in Portland and one in the Department of Human Services Building in Salem. Legislators got the chance to see people who really need care, and who are having good care right now through CareOregon. There were testimonials that were heart–wrenching.

Do you have any final statements to make about your work?

I would say I work out of a state of mind. When I’m photographing the dwarf in the circus, I’m confronting myself as a giant compared to this dwarf, but I’m not a giant compared to other people who might be a foot taller than I am. So then I confront another reality; I’m in another state of mind. Even in the Civil Rights Movement I’m erasing my own heritage and the town I grew up in. We didn’t have any social experience with black people at all. So I’m learning about that oppression as I go deeper into the Civil Rights Movement. And East 100th St. is another frame of mind. Then I work on that. I don’t read an article in The New York Times and think, well, that’s a good idea, I’ll work on that. No, my work is very personal. It’s a personal barometer of my life, a voyage of consciousness that is my life’s work. Each one is different. My wife says, “You always start with zero, you erase your clichés,” as I did in Paris. You’re only seeing what I ended with, what I felt the thing is. So there’s a psychological, there’s a visual, there’s a contemporary, there’s an artistic element.

I, personally, have been printing my body of work during January and February for the last two or three years, and I’ve accumulated about 1,200 prints in that time. I’m doing it because it needs to be done. One of my publishers, Gerhard Steidl, who does beautiful, highest–quality work, and who published England/Scotland 1960 in 2005 and Circus in 2007, is talking about publishing a four or five volume set of books of my life’s work. That would be great, if it happens.

I would also like to give my wife Emily credit for her keen intelligence, visual acuity and inspiration through all these years that we have lived and worked and raised our children together.

Jain Kelly was the assistant director of The Witkin Gallery in New York City from 1971-78. She has written numerous articles on various aspects of photography and is a fine-art photography consultant to collectors. Her email is [email protected].

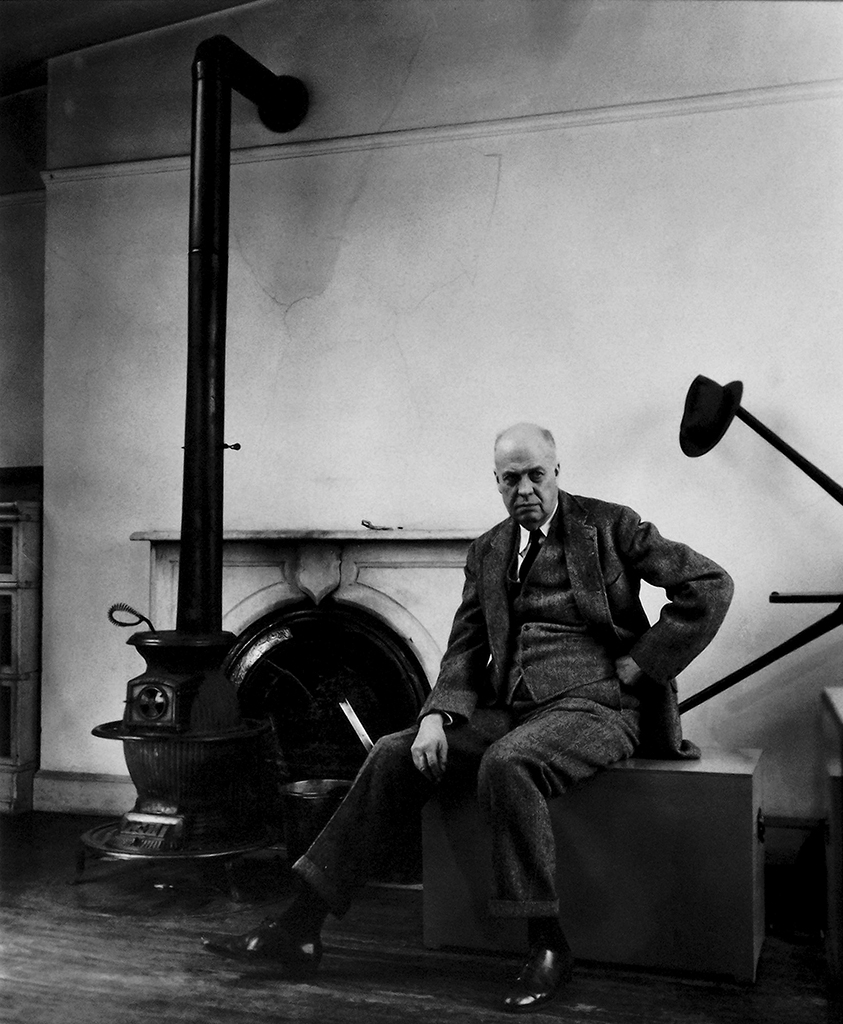

]]>Sandra Phillips is Senior Curator of Photography at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, an institution that has dynamically supported and collected photography since its opening in 1935. Phillips received a B.A. in art and art history from Bard College in 1967 and an M.A. from Bryn Mawr College in 1969. She earned a Ph.D. in art history in 1985 from City University of New York, where she specialized in the history of photography and American and European art from 1849 to 1940. Phillips has written and lectured widely on photography and is the author or co-author of several books and catalogues. Her recent exhibitions include: “John Szarkowski: Photographs”; “Diane Arbus Revelation”; “Police Pictures: The Photograph as Evidence”; and “Shomei Tomatsu: Skin of a Nation.” Despite the globalization of media and the arts, regional differences are a curious reminder that a sense of place still informs our imagery. Sandra Phillips has an unusual vantage point having grown up with the New York’s MoMA and overseeing the photography collection at SFMOMA.

All of your university degrees, including your Ph.D. from the City of New York, are in art and art history where you specialized in the history of photography along with American and European art from 1849 to 1940. Did you have a primary mentor for the study of photography’s history at that time?

No, but I grew up in New York and loved museums, and I consider myself a student of the work shown at the MoMA. In fact, I remember seeing the show, “New Documents.” I remember seeing the Arbus pictures because I went with a friend, and she thought it would be fun to go. I remember seeing a man spit at some of the pictures in the show.

When did you gravitate towards photography as a field of study?

I come from a family of art people -my dad was an architect, my mom a landscape architect, and I thought I would be a painter, so when I went to school, that’s what I studied. But I became more interested in looking at art, and it seemed really interesting that no one was then taking the history of modern American art really seriously -this was in the 60s. And then when I got more involved in modern American art, it seemed that one of the major contributions was in photography, which was even less studied, and that intrigued me even more.

Under the direction of curator John Humphrey, SFMOMA was one of the first museums to recognize photography as an art form, over 70 years ago. Can you tell us what initiated that recognition and began the process of creating the SFMOMA’s photography collection in 1935, the same year that it opened? Was there a special collection donated to the museum at that time?

The San Francisco Museum of Art, as it was then called, was founded by a group of wealthy local individuals. You realize that San Francisco became a city very suddenly when gold was discovered, so everyone in the world was interested in San Francisco, and the 49ers were here and many of them used the services of the daguerreotypists to send records of their recent fortunes back home. There has been a very strong interest in photography here since the 19th century–remember Carleton Watkins, Muybridge, and others used this as their base. There has never been a tradition of important art created here -that is relatively new, but when the museum was founded in the 30s there was an impressive range of important photographers he could own or lease. This might include tents, caves, pictures made within buildings, etc. He is still an active collector, and I tease him that we’re planning the Return of the Paul and Prentice Sack Collection.

SFMOMA recently received another significant donation from the Emil & Silverstein Collection. What distinguishes this collection from the Sack collection?

This is a very different collection. I would describe the pictures as psychologically informed. It is historical, but the emphasis is on work of surrealist inflection produced in the 1930s and the present. The pictures are also in their own way very personally meaningful to their owners, in a very different way from

the work in the Sack collection.

SFMOMA prides itself as having from the first, viewed photography as a modernist art form. Its collection of over 15,000 prints is known for it’s early American and European modernist photographers as well as Western American Landscape photography. How does modernist photography differ from contemporary photography? Would you define photography in the same terms today as in the days of your predecessor, Van Deren Coke, who established the department of photography in 1980?

I would define modernist photography as photographs which aspire to modern art, and which were made by Americans and Europeans in the 1920s and 30s, essentially. Since I came to the museum, in 1987, I have enlarged the scope to include 19th century and have emphasized our tradition of landscape representation. Coke thought about photography in terms of modernist art -I believe the concerns of contemporary photographers are related but different.

In 1980 the exhibit “California Photography 1945-1980” examined the aesthetic and history of photographic image-making unique to California. Do you think there remains a special sensibility that divides West Coast from East Coast photography?

First, I had nothing to do with the California show, but yes, I would generally say that in the west there is an abiding interest in land use and land issues, which is not generally shared by photographers or audiences for photography in the east.

In California today, what influences define West Coast photography?

There is more of an understanding of Asia here.

Before coming to SFMOMA in 1987, you were the curator at Vassar Art Gallery in Poughkeepsie, New York. Did your experience at Vassar provide you with a heightened sensitivity to women photographers?

Not really, I was there for about a year. But in general, photography has provided women with opportunities not so obvious or available in other fields.

You have organized exhibits and written numerous essays on women photographers, most notable Dorothea Lange in 1994 and Helen Levitt in 1991. Your essay “Women Artists in California & Their Engagement in photography” appeared in the book Art/Women/California 1950-2000. What special concerns faced women photographers in the past, and do you believe that many of those photographers may still be undervalued?

If you mean monetarily undervalued, I suppose you could say that, but this is an aspect of the field that really doesn’t interest me too much. The “concerns” that women faced in the past are ones they -we -face today. If we are mothers who need to work, how do we do this? That is probably the most obvious difference.

There is an interesting story about one of Dorothea Lange’s most famous photos, a migrant farm worker named Florence Thompson. As Lange’s photo gained wider recognition and value, Florence and her children came forward, angry that neither monetary compensation nor a copy of the photo were ever given to them. You recently organized the Diane Arbus exhibit, another controversial photographer often accused of exploiting her subjects. How do you address this issue when the subject comes up?

Well Lange worked for the government, she had a job, and her photographs were made to serve a purpose, one that she very much believed in; then the times changed. I do not think she would have said she was exploiting her subjects. And frankly I don’t feel comfortable with the idea that Arbus “exploited” her subjects either, they look very interested in her, as much as she in them. When she was making these images, they were very new, very raw material. I don’t think you would see anyone today spitting on her photograph of a young man in curlers, as I saw in the MoMA exhibit “New Documents.” I think we’ve become more tolerant, as a culture.

Documentary photographers, such as Dorothea Lange, never anticipated their work on a museum or gallery wall. Their photographs told a story meant for the printed page of national magazines. It seems that today’s documentary photographers anticipate a museum or gallery exhibit along with a well-designed coffee table book. Do you think that the nature of documentary photography has changed to appeal to a more limited audience?

Photography has changed technologically, and the ambition of certain photographers has changed, I think that is the way I would put it. Someone wise once said that the process gets easier but the number of important photographs remains the same. There is a lot of indifferent work being made, but some very interesting work as well.

Many of the snapshots of today, along with the news photos of our time, are in digital form. It is very likely that no “paper trail” will exist in the future for these kinds of images. The history of fine art photography is filled with images that were never intended to be considered fine art. Is this concept lost forever to future collectors and curators?

If so, maybe that is not such a bad option -look at all the bad stuff out there, and consider all the time needed to sort out the good from the dull.

You’ve spent a good deal of research time at the Vatican Photography Collection and recently received a Getty fellowship to return to Rome and continue your research. What special fascination does

this collection hold for you?

It’s mainly unknown work by unknown photographers from all over the world.

With John Szarkowski, you organized a major retrospective on Ansel Adams, in 2001, then curated a major retrospective of Szarkowski’s photographs that recently traveled to the NY MoMA. What’s next for SFMOMA? Any future plans for another major retrospective such as one on Van Deren Coke?

My next big project will be on voyeurism and surveillance. I’m working on a big exhibit about things that are forbidden to be photographed: like violence and death and sexual images. It is also about how we are watched and our ambivalence about photography. It is about a culture that is ferociously looking at images that are taboo.

SFMOMA is located at 151 Third Street (between Mission and Howard Streets) San Francisco, California. For general information call (415) 357-4000 or visit www.sfmoma.org.

Kay Kenny is a photographer, writer, and teaches photography at ICP, NYU and SHU, web: www.kaykenny.com, e-mail:[email protected].

]]>Throckmorton Fine Art is pleased to announce an exhibit of photography that focuses on women in Latin America, especially indigenous women from the region. There are some fifty photographs in the exhibit, nearly all of them in black- and-white. The photographs are from the most celebrated photographers who have worked in the region. Included are images by Henri Cartier Bresson, Tina Modotti, Laura Gilpin, Helen Levitt, Fritz Henle, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Lola Álvarez Bravo, Mariana Yampolsky, Nacho López, and Héctor García. Also featured are works by distinguished contemporary photographers working in Latin America: Mario Algaze, Valdir Cruz, Javier Silva Meinel, and the two Mexican photographers who are renowned heirs of Manuel Álvarez Bravo, the “father of Mexican photography”: Flor Garduño and Graciela Iturbide. Finally, there is innovative new work by the niece of Frida Kahlo, Cristina Kahlo.

All photographers who have worked in Latin America, male and female, have at one time or another been drawn to the women of the region as a subject. There is the beauty of the women of Latin America, but there is also their strength and their admirable resilience. The women of Latin America are powerful, often serving as heads-of-households, recognized as such or not, and they maintain families under often adverse circumstances.

The novel coronavirus pandemic has hit Latin America hard: the region has 8 percent of the world’s population, but it has had 30 percent of the world’s infections and 36 percent of the world’s deaths from the disease. Governments have often been of little or no assistance, forcing communities to fend for themselves. Women have often been the linchpin of community—and family—efforts at perseverance.

Flor Garduño, Embrace of Light / Abrazo de luz, Mexico, 2000, Gelatin silver print, printed later 14 x 11 in., Signed in pencil on verso, (Inv# 74822-C)

The photographs included in the exhibit offer portraits from throughout the region, including from Mexico, Guatemala, the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Peru, and Brazil. Women are shown at rest, at labor, playing with their children, praying, sleeping, and even daydreaming (according to the title of a photograph by Manuel Álvarez Bravo). The photographs are all accomplished works of fine art, distinguished for their compositions, their mastery of light and shadow, and their quality of printing (nearly all are gelatin silver prints). All of the photographs, too, give women, even those living in poverty, a deserved dignity.

This exhibit is a tribute to the strong and proud women of Latin America. A catalogue accompanies the exhibit. It features an essay by Graciela Kartofel.

Throckmorton Fine Art is located at 145 Est 57th Street, 3rd Floor, New York, NY 10022. You may visit their website at www.throckmorton-nyc.com, or call them 212.223.1059.

]]>One characteristic of Magnum, perhaps of cooperative and collective enterprises generally, is that the purpose of the organization is fluid, constantly open to the interpretation of its members and the wider community engaged with it. Magnum has a constitution of rules and by-laws that it needs in order to function, but the organization has no official statement of artistic intent and has never had an über-maestro to act as its interpreter-in-chief. At least, never for long. The group is a convocation that gathers regularly, in part to discuss why it is there. Magnum means and has meant different things to different people—a tabula rasa onto which different ideals for the medium and for the role of the photographer are projected. It has traditions for sure, but any core or underlying set of beliefs asserted on its behalf—this often happens, often with passion—is invariably in competition with an alternative set of beliefs asserted by others with equal conviction. Different journalistic and artistic ideologies, advanced by particular individuals and like-minded groups, ebb and flow. The dominant ideas of Magnum’s past—the confident simplicities of the principled photojournalism of its pioneers, the idea of the concerned photographer conjured in Cornell Capa’s exhibition title, “The New Photojournalism” as coined by Gilles Peress—have left their mark on Magnum’s traditions and their influence on photography. Each eventually makes way for others.

Today Magnum acknowledges its pluralism and eschews a corporate or ideological position. Accommodating a diverse range of documentary image-makers from collectors of pointed visual evidence to graphic expressionists, it has made diversity and diverging views a central plank of its contemporary identity. In this respect, competing ideas about artistic and social purpose continue to characterize the organization, just as they have since it began. What this means for the photographers is that all are subject to constant challenges regarding their individual purpose as both artist and community member. This peer pressure is part of Magnum’s group dynamic, its culture.

The mythology of Magnum relies on the contribution to the unfolding story of photography made by its past and present members. It has been around 60 years since Magnum began with the visionary guiding spirits of Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson. It will last as long as its photographers remain loyal to each other. But it is the restless striving that makes it unique in the world of photography; the way in which individual members are drawn to and then respond to the call of the convocation, to the legacy of the group’s history of purpose—to the competing ideas of what documentary photography is for—and to each other, that changes them. Photographers who have spent any time within Magnum are not the same photographers as they would have been otherwise.